SOMETHING REVERBERATED

There were once trees growing under the roads. There are still creeks flowing beneath the directional pathways we’ve imposed.

Gracia Haby & Louise Jennison

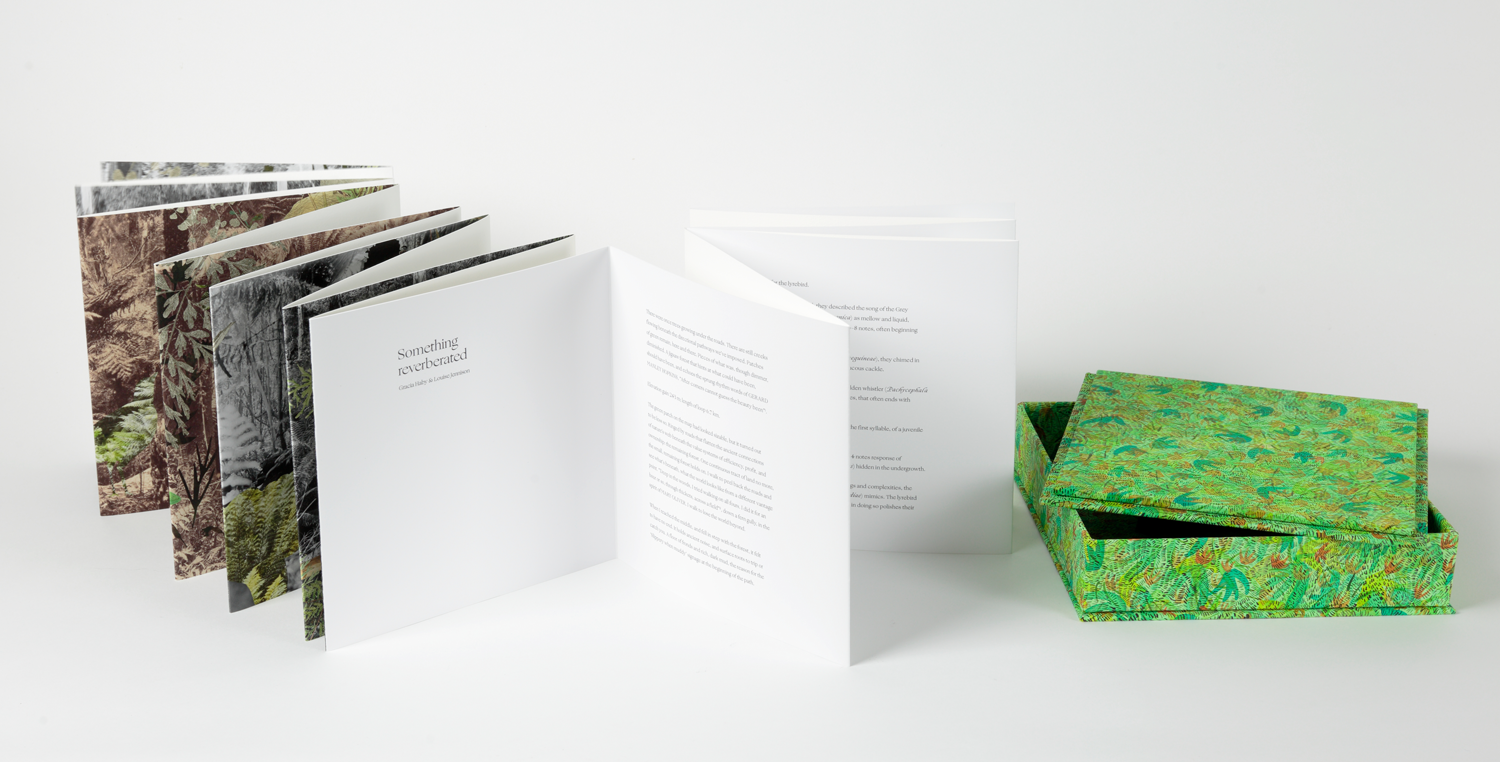

Something reverberated

2021

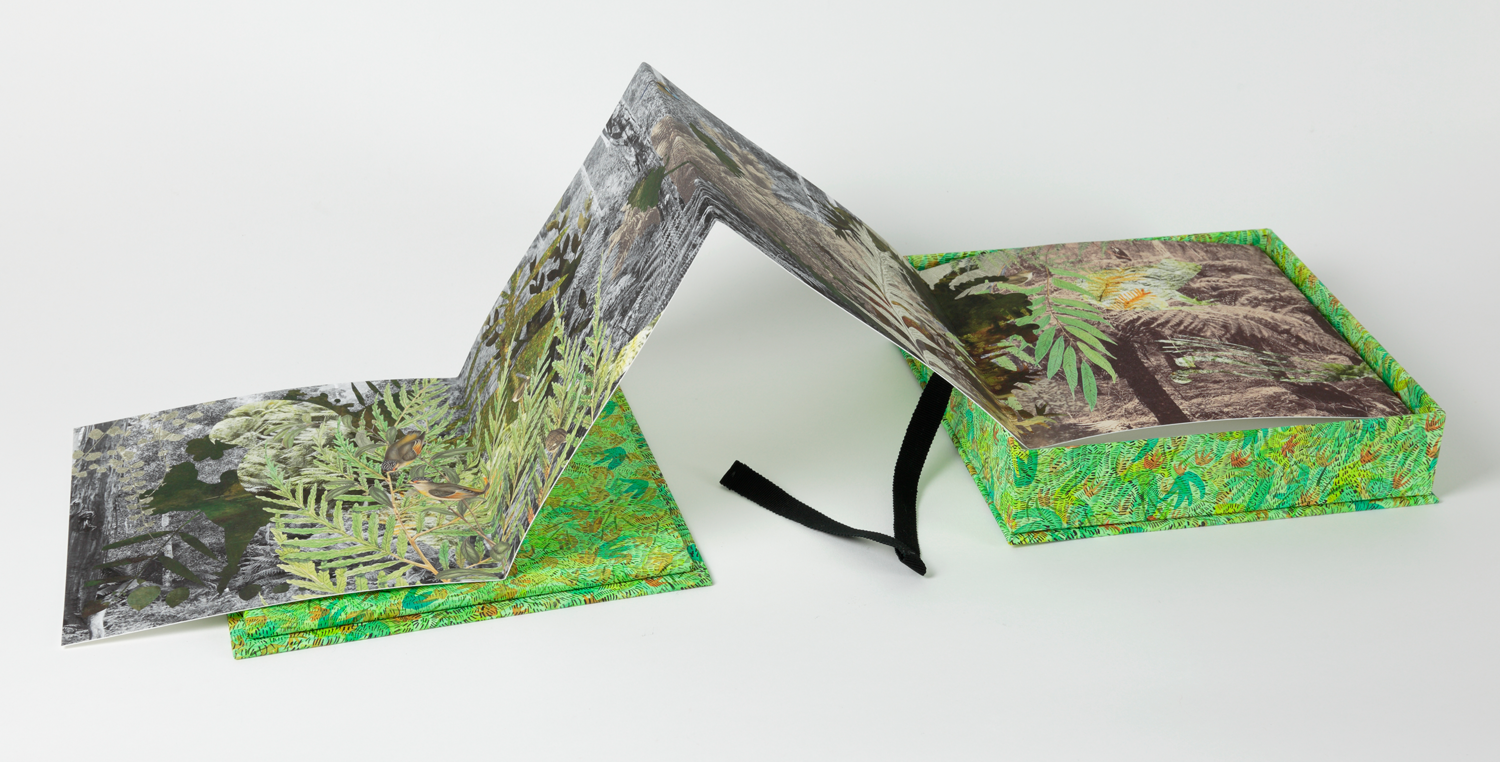

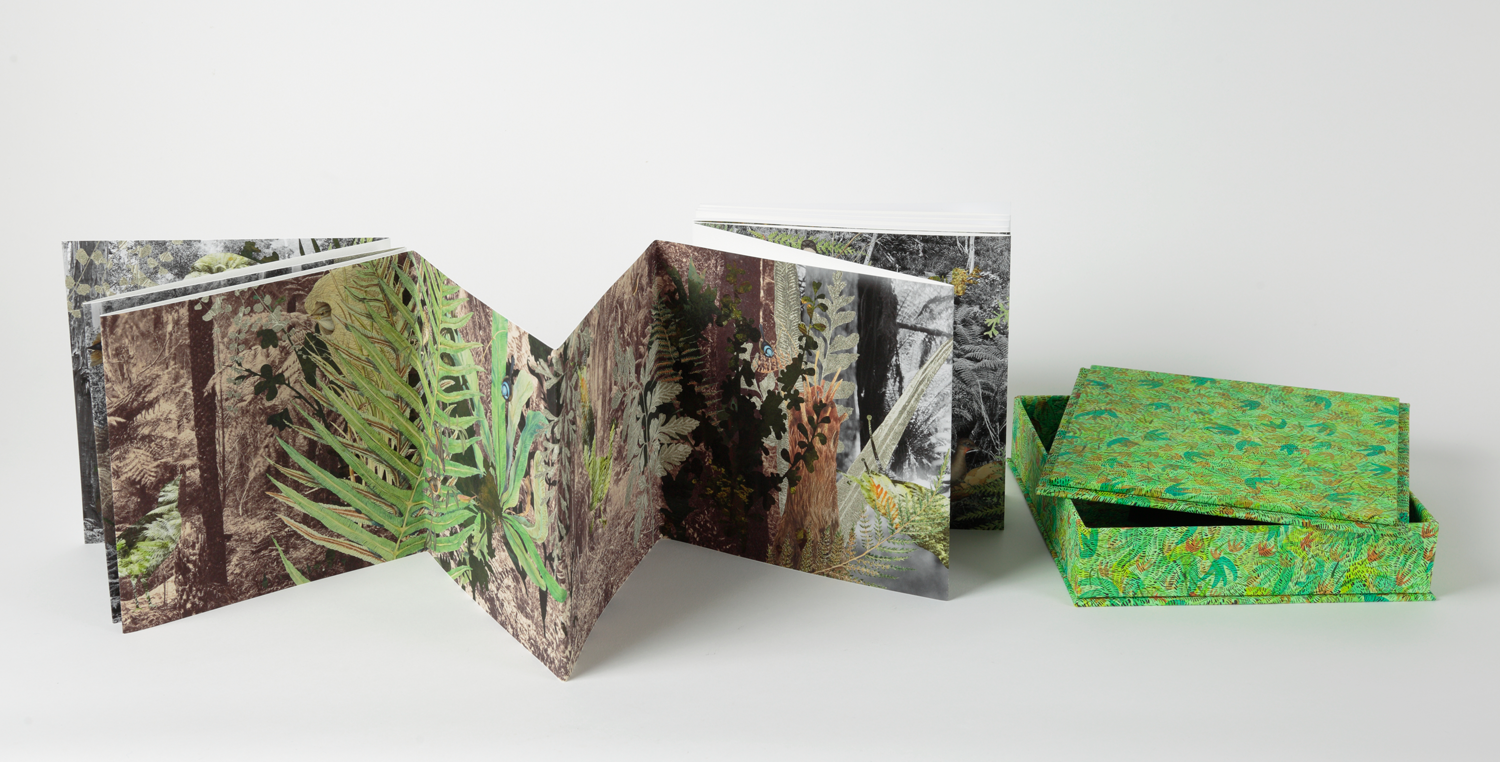

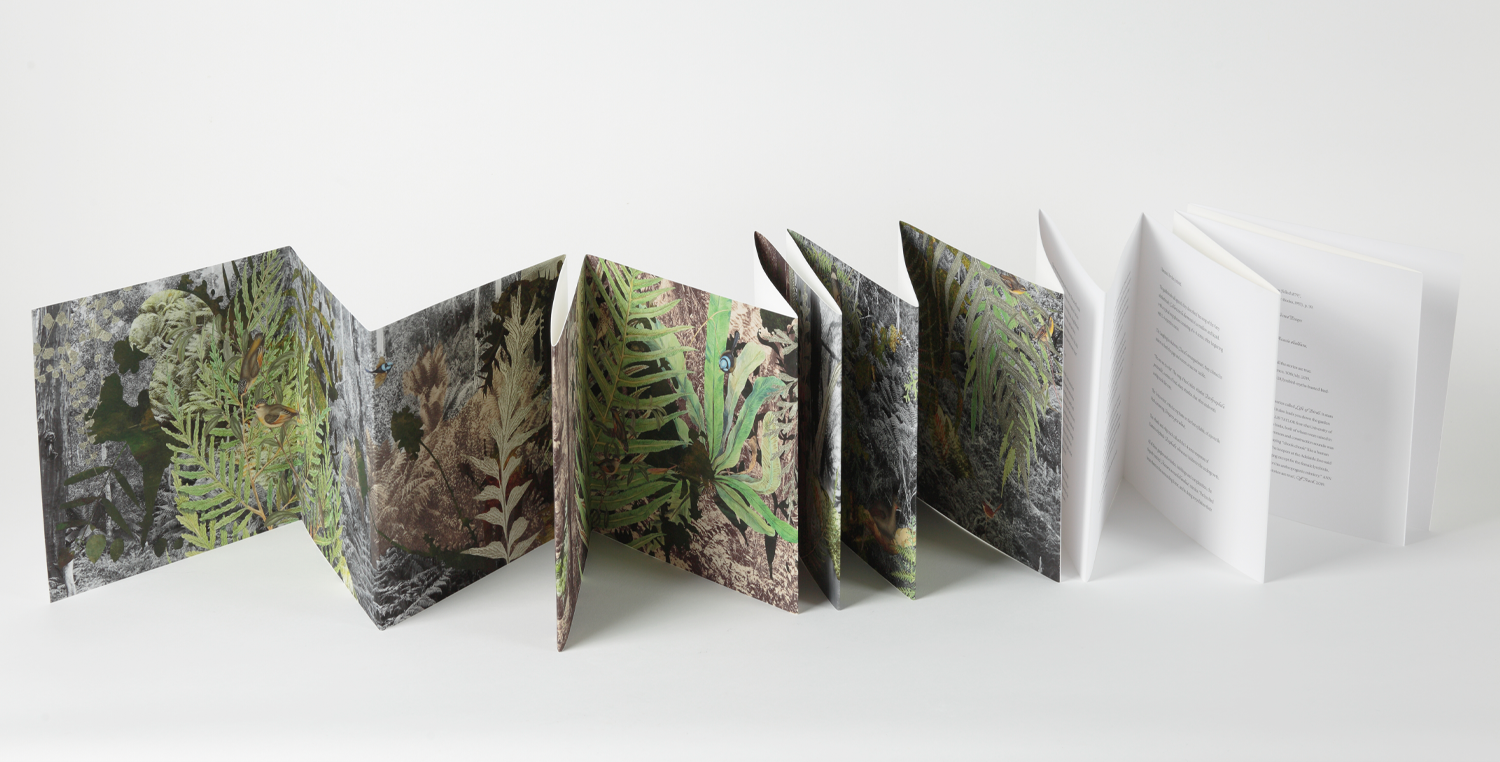

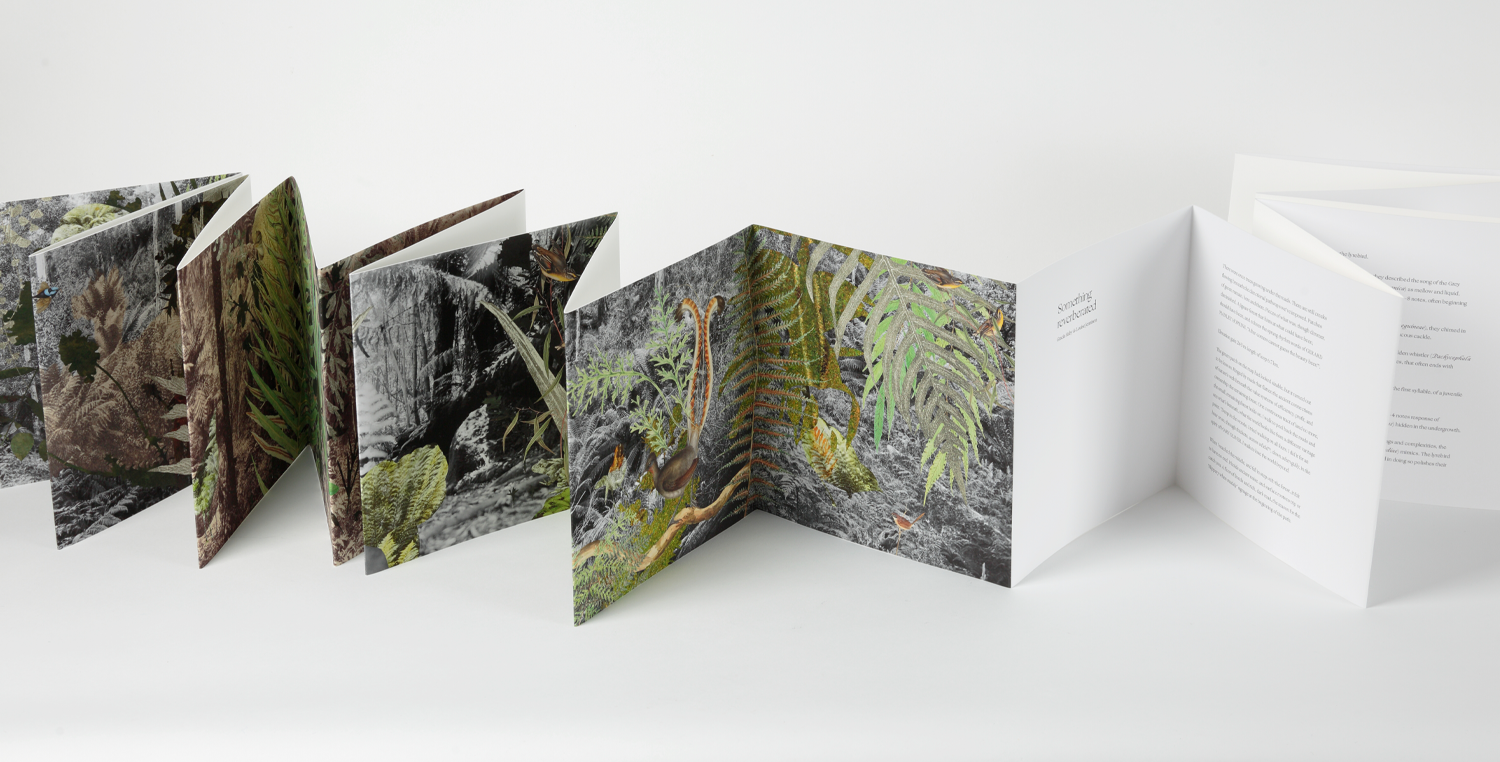

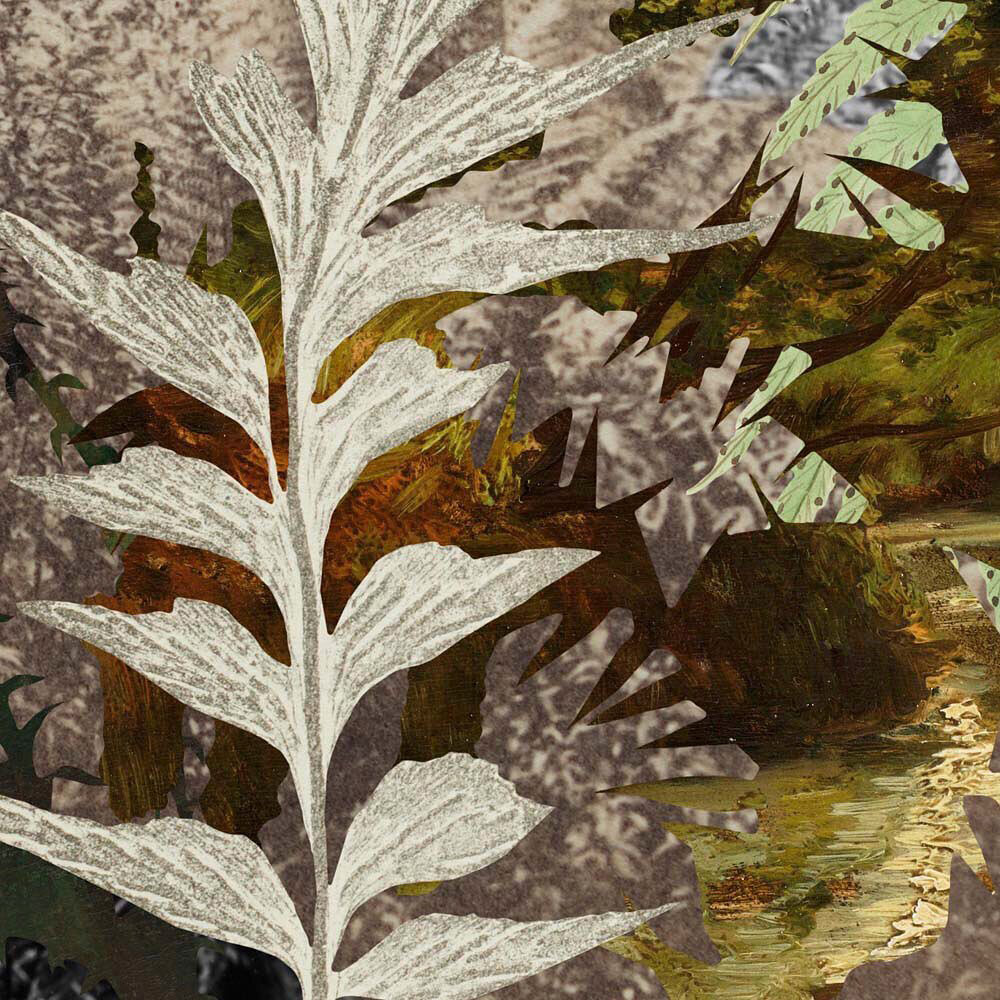

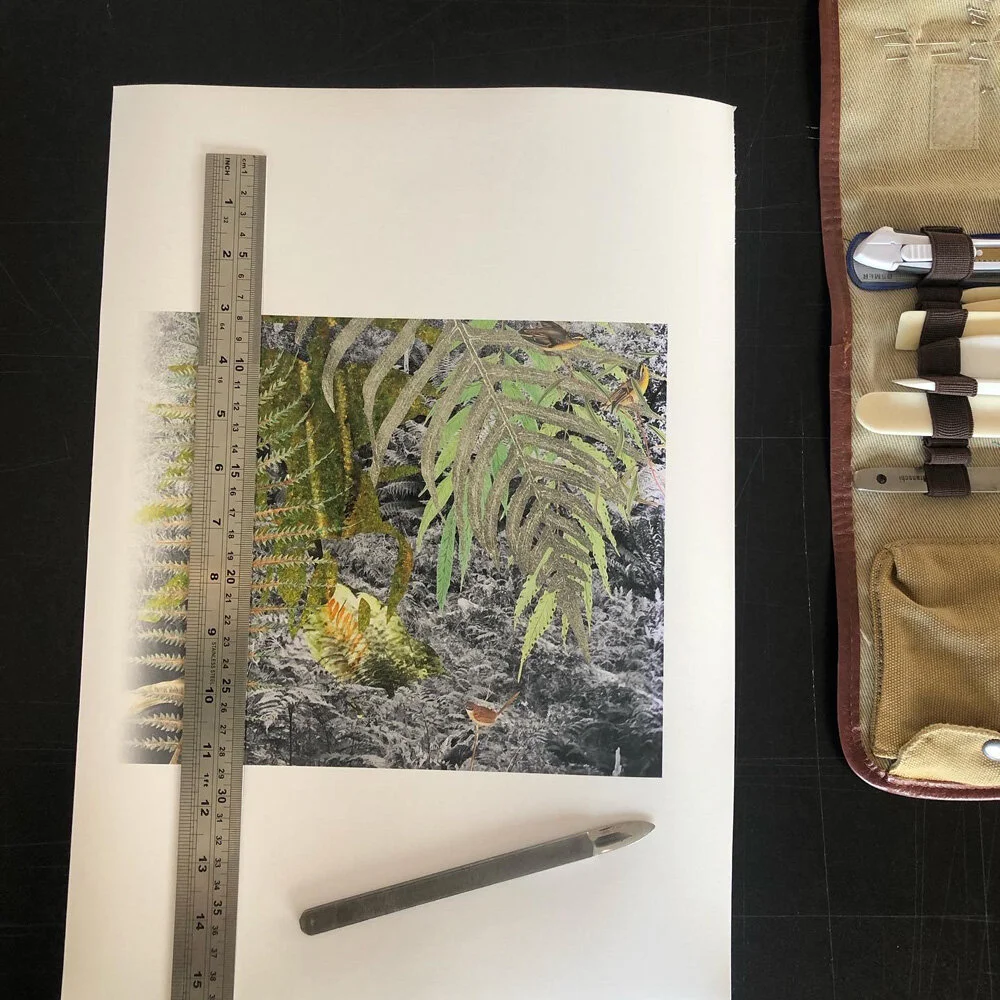

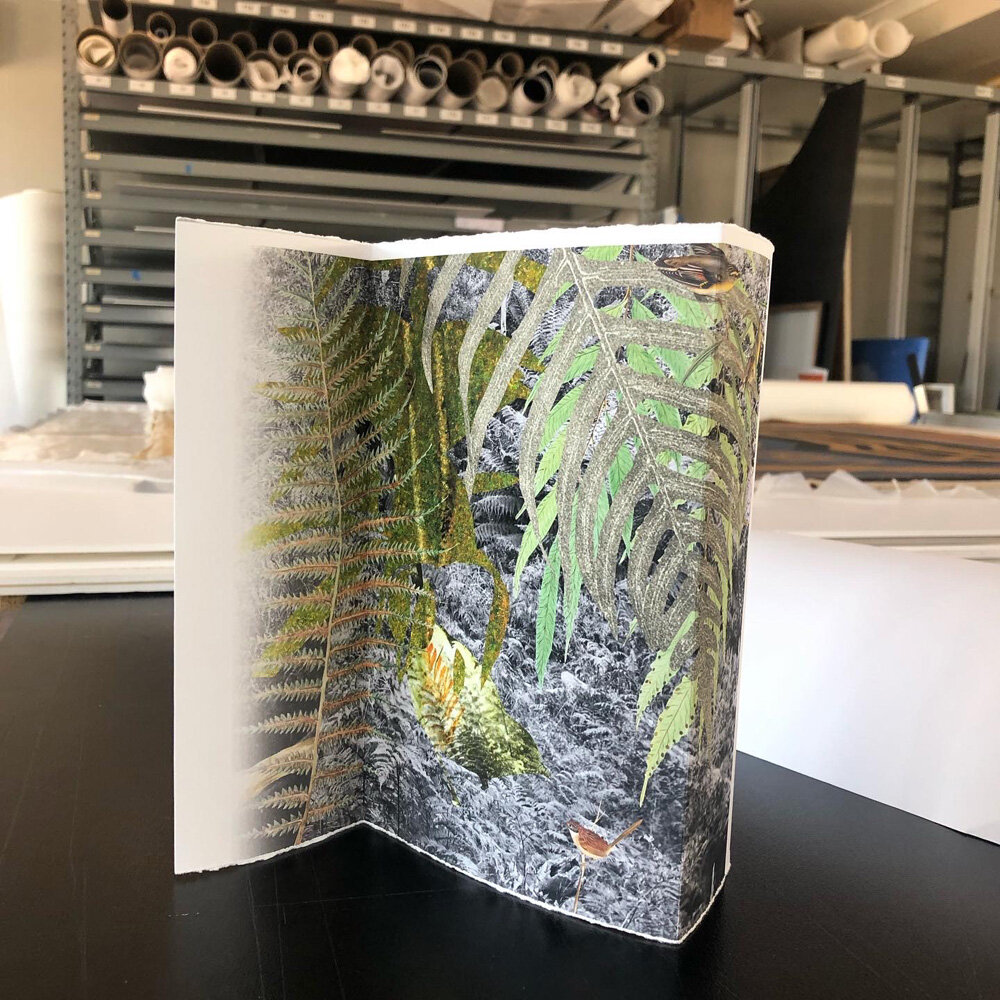

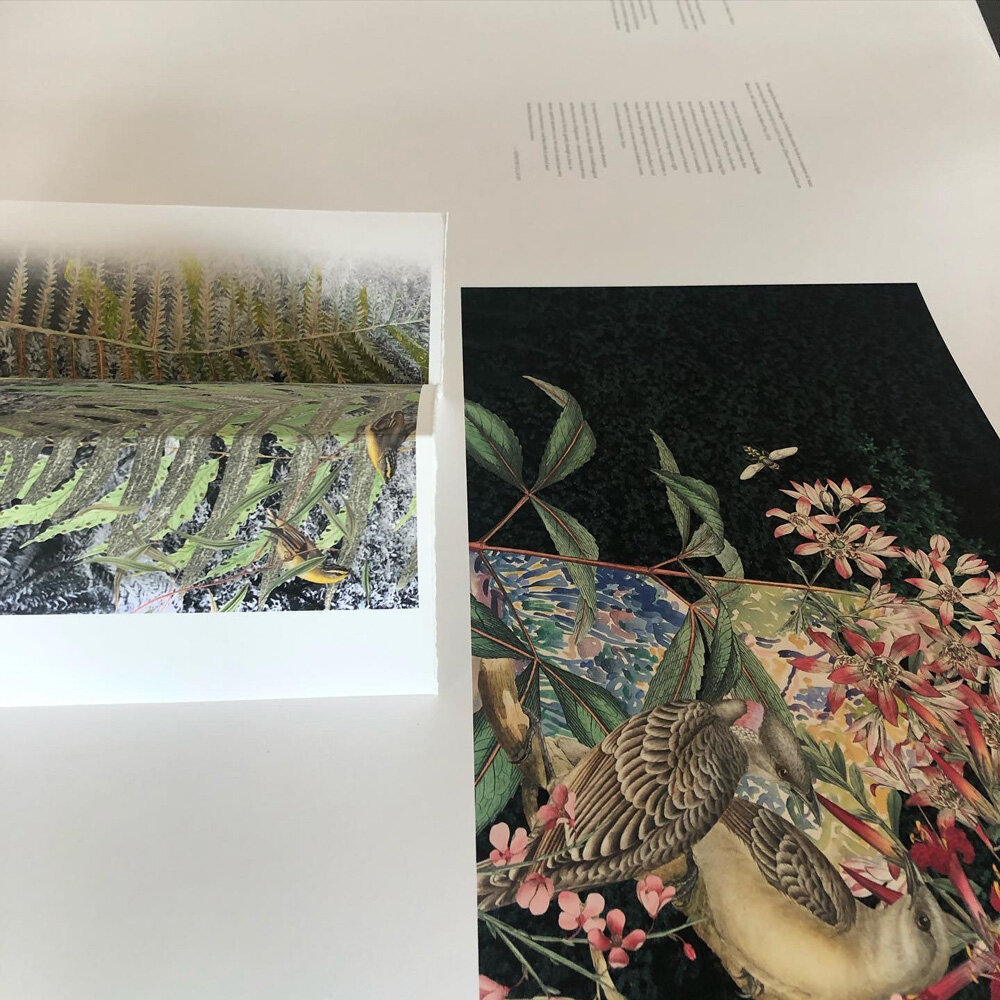

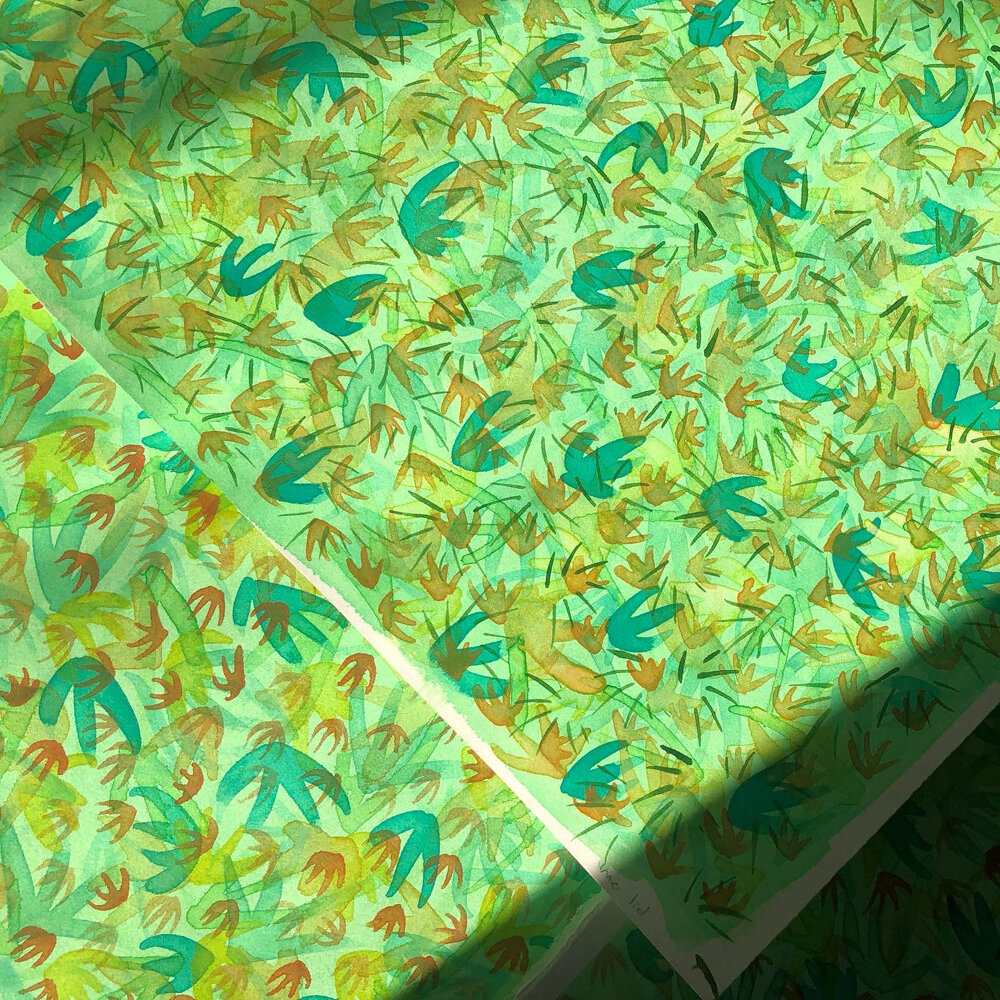

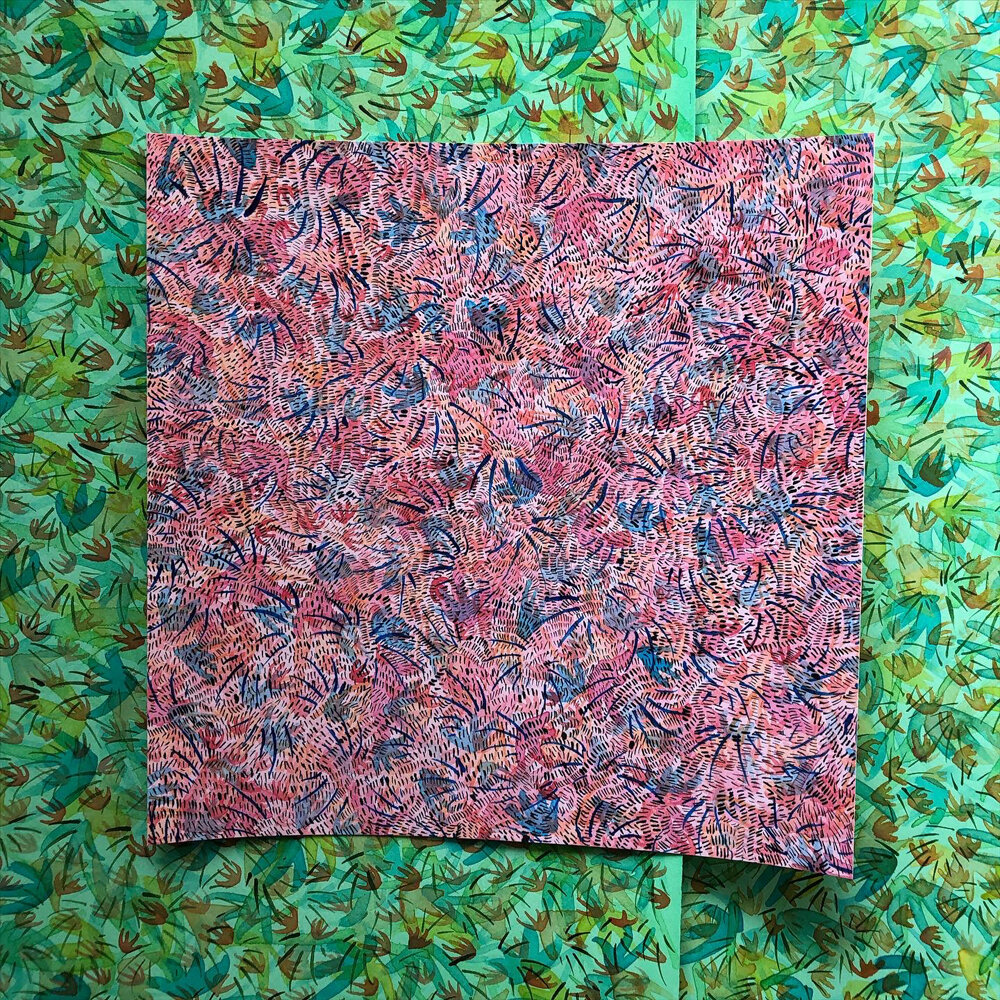

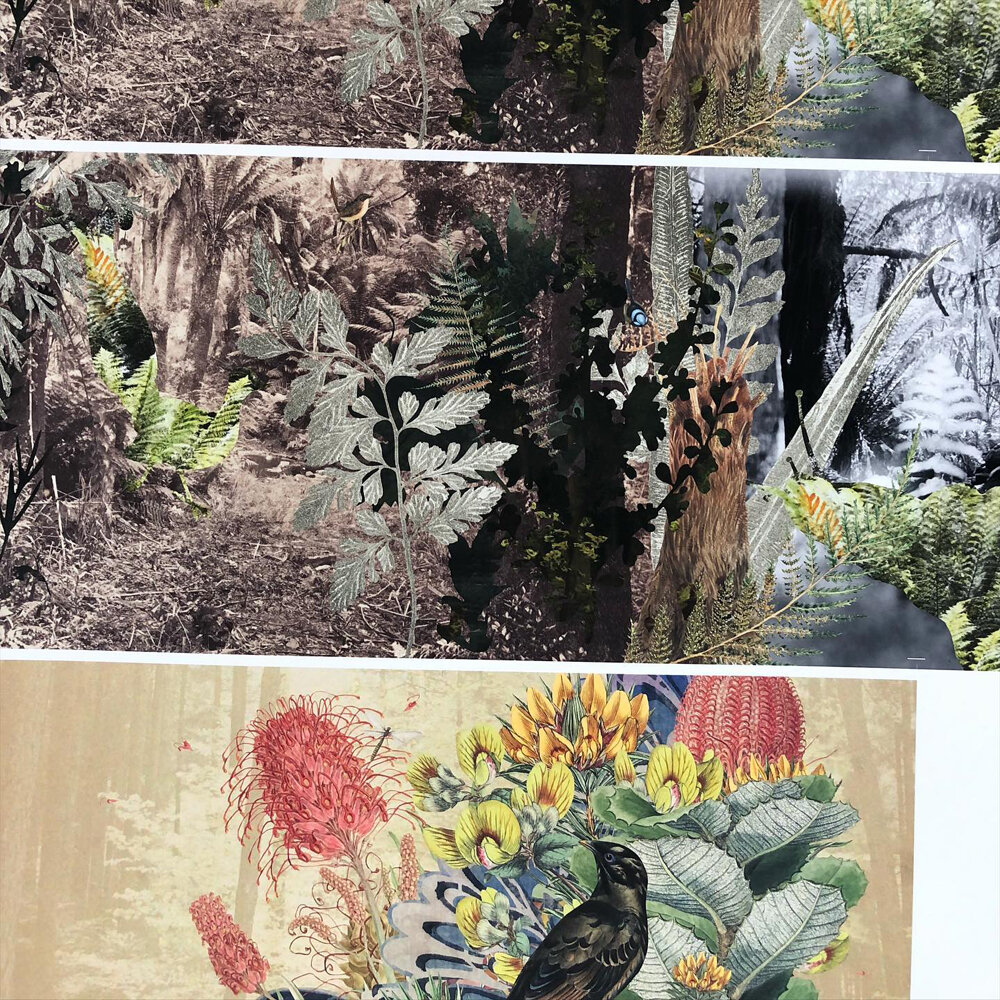

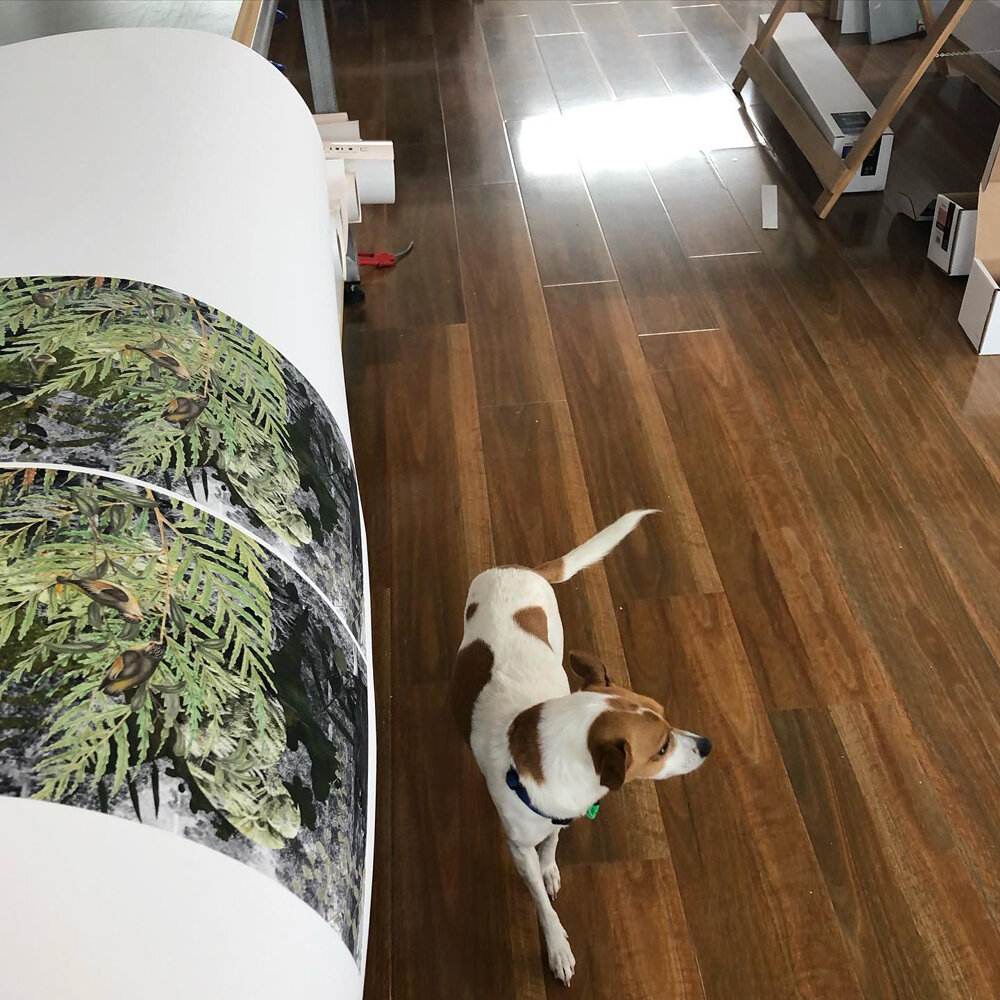

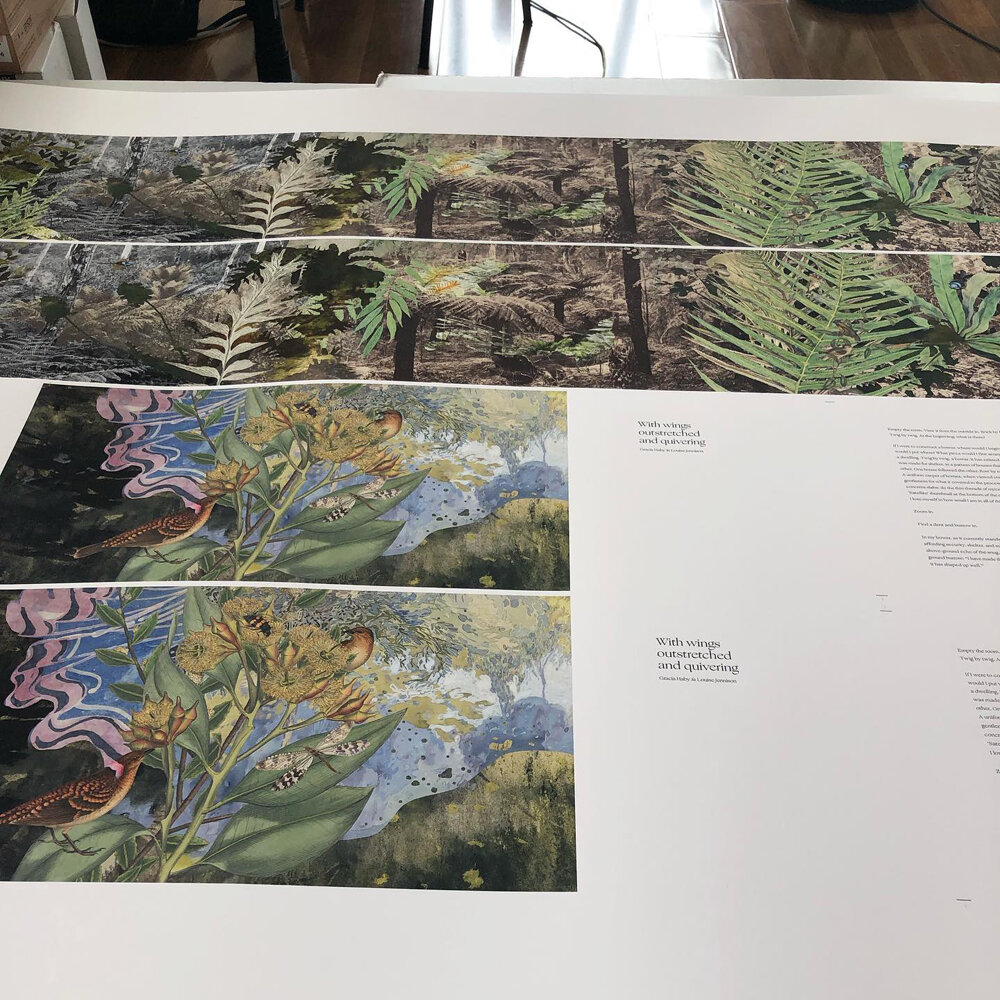

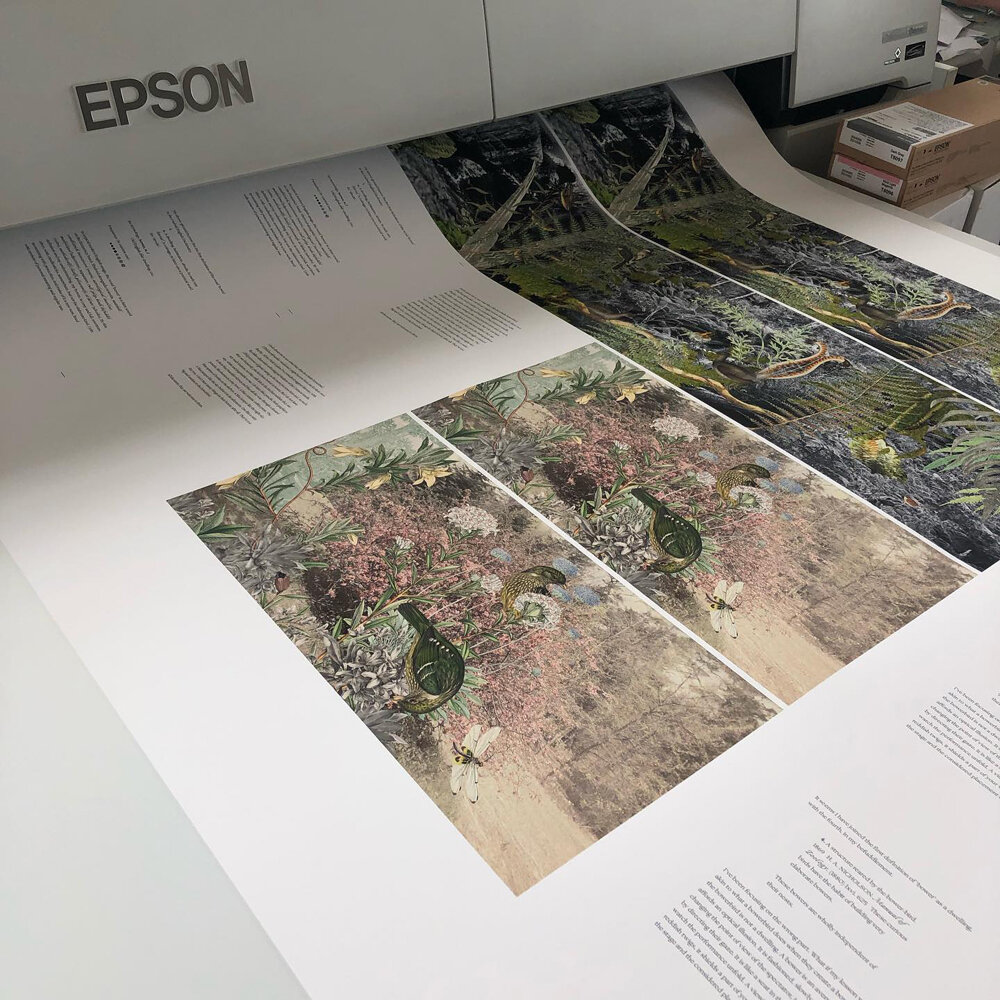

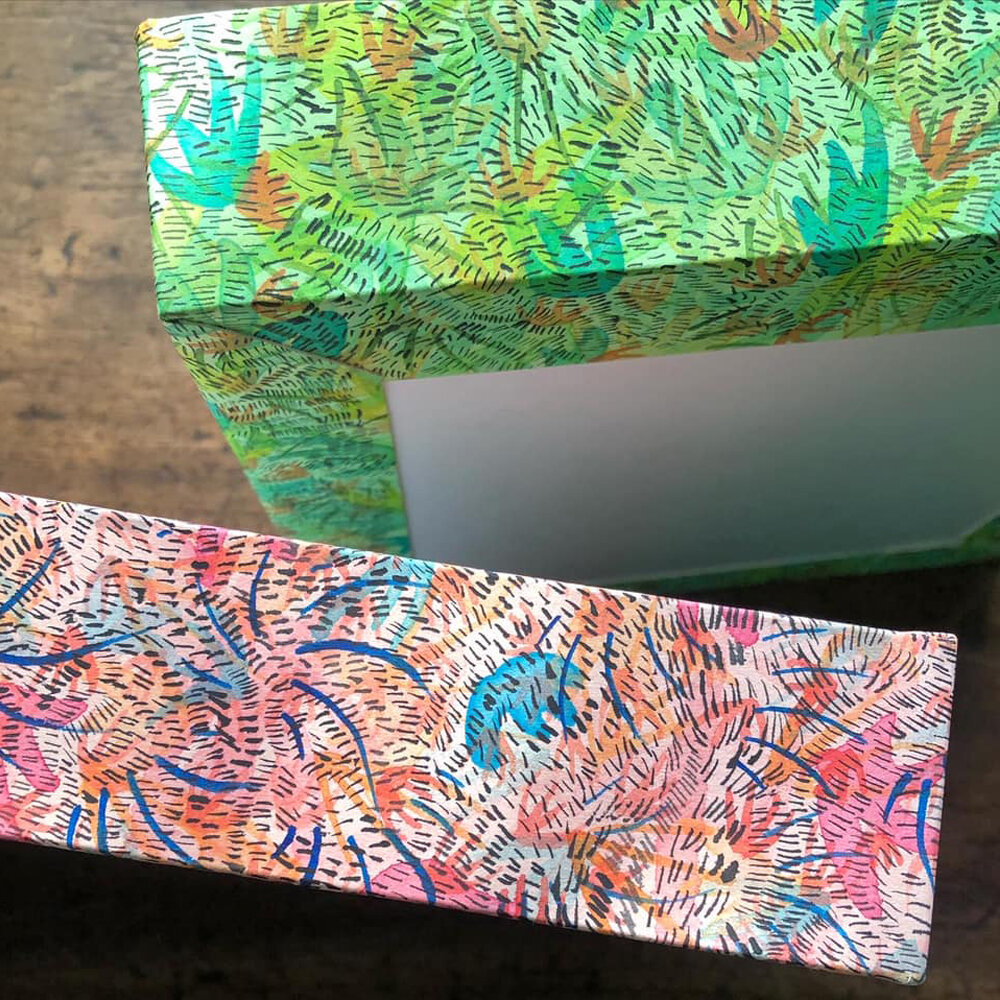

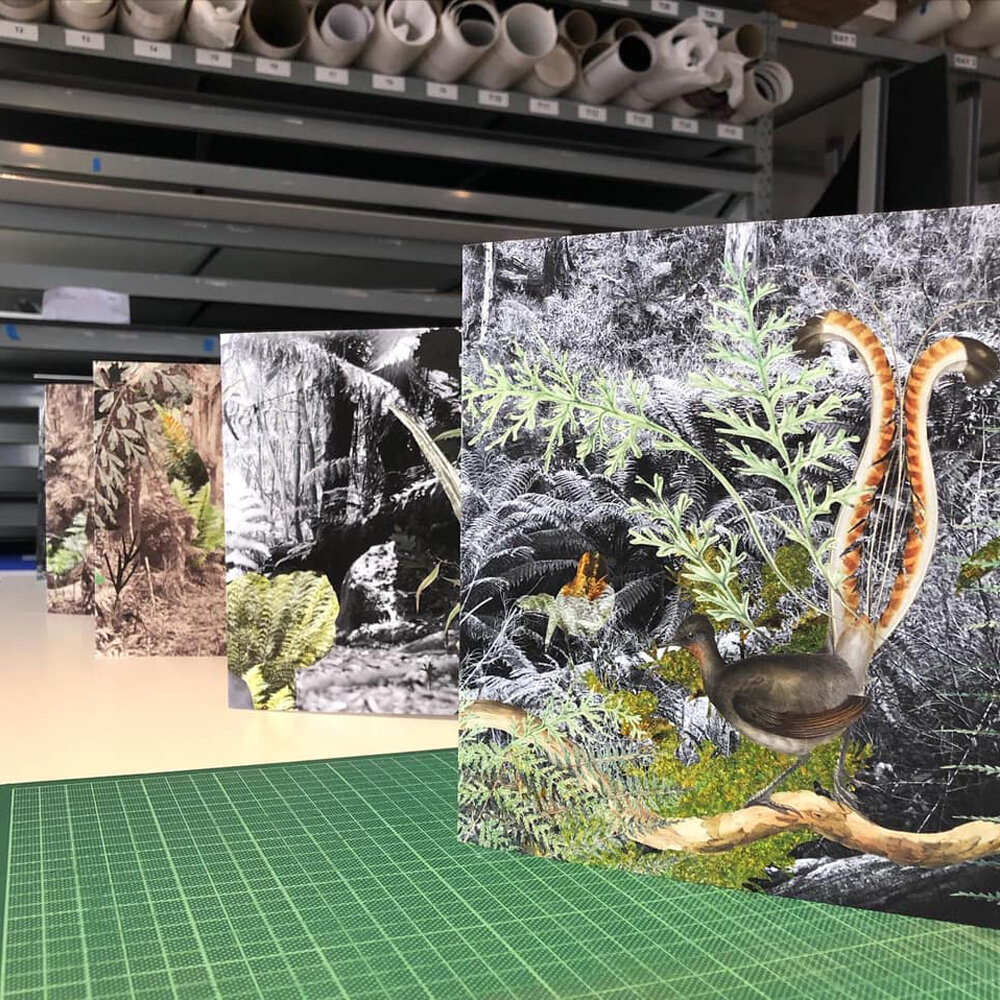

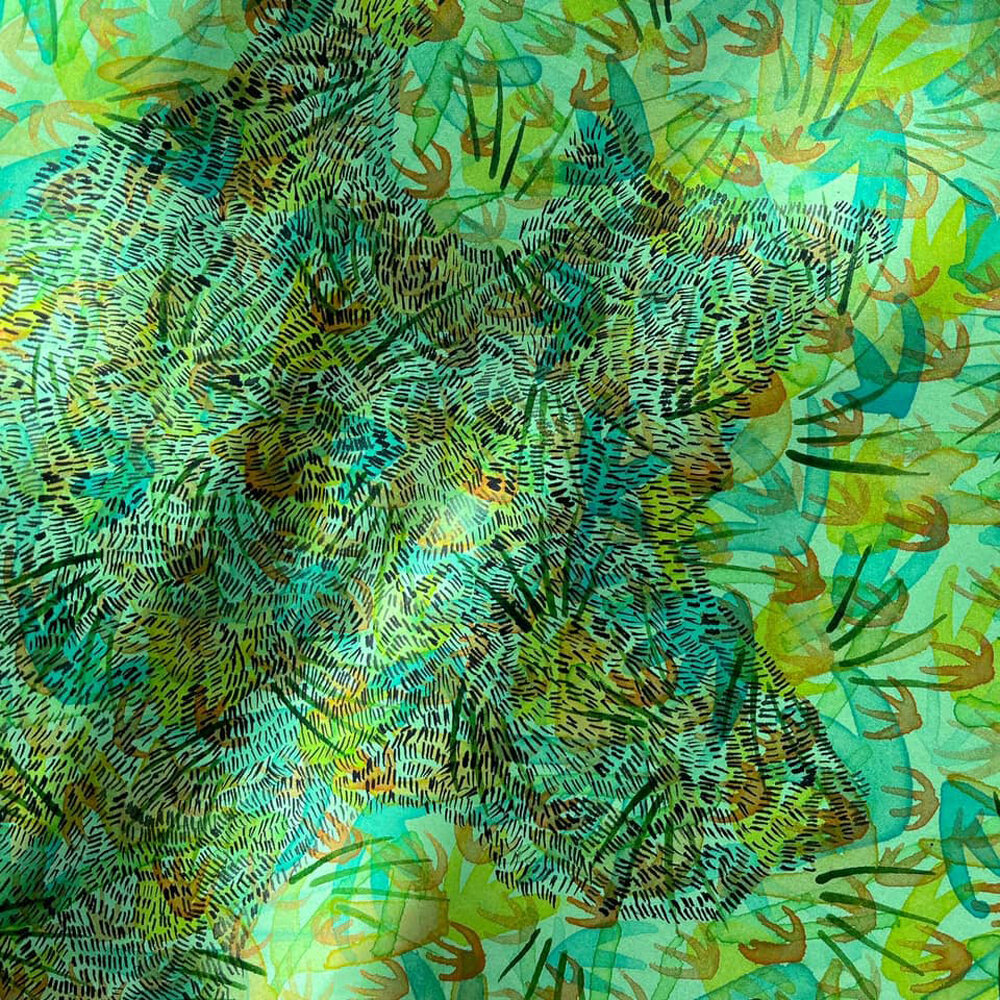

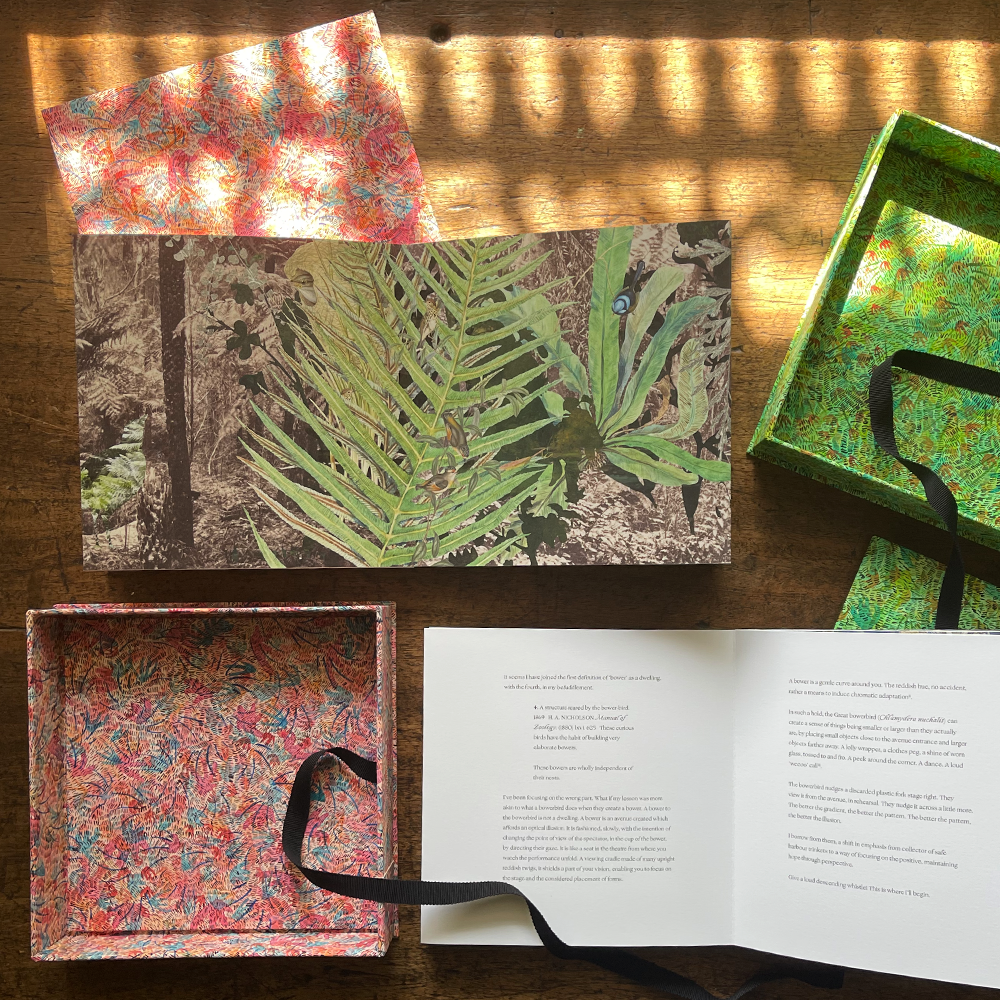

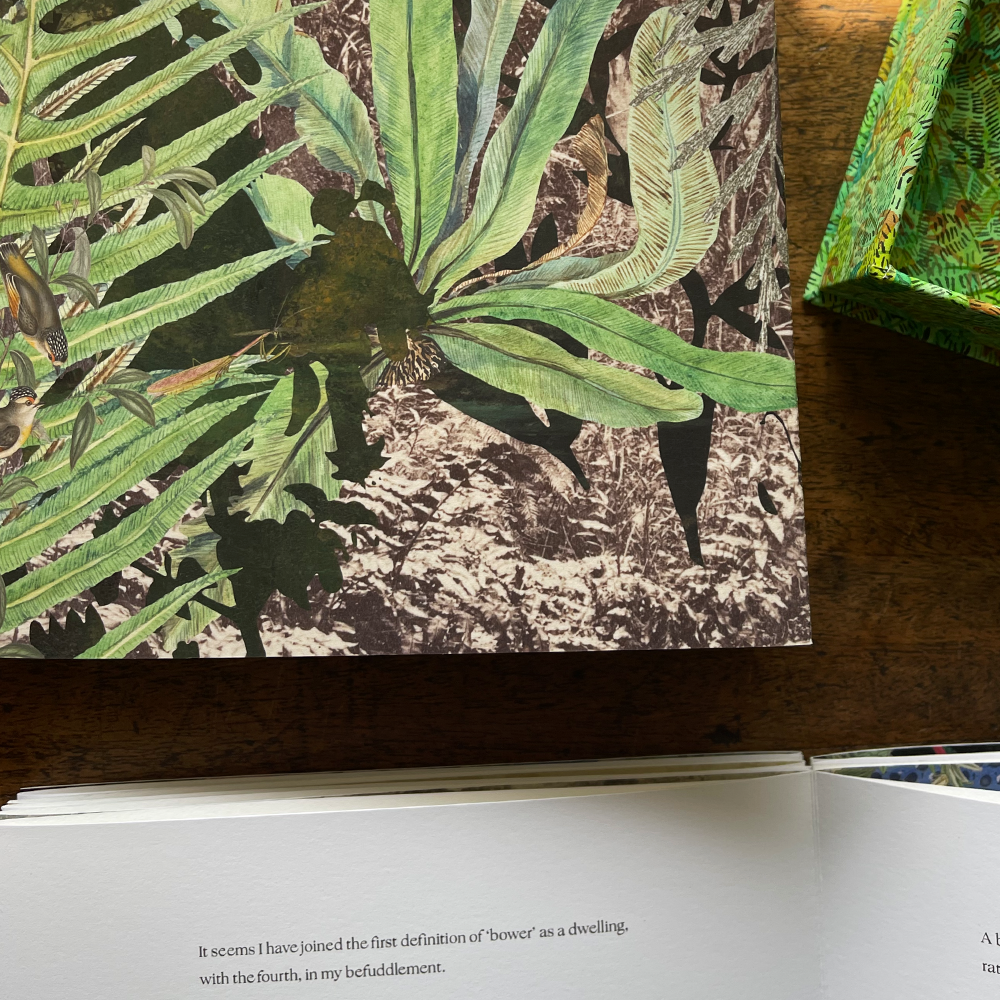

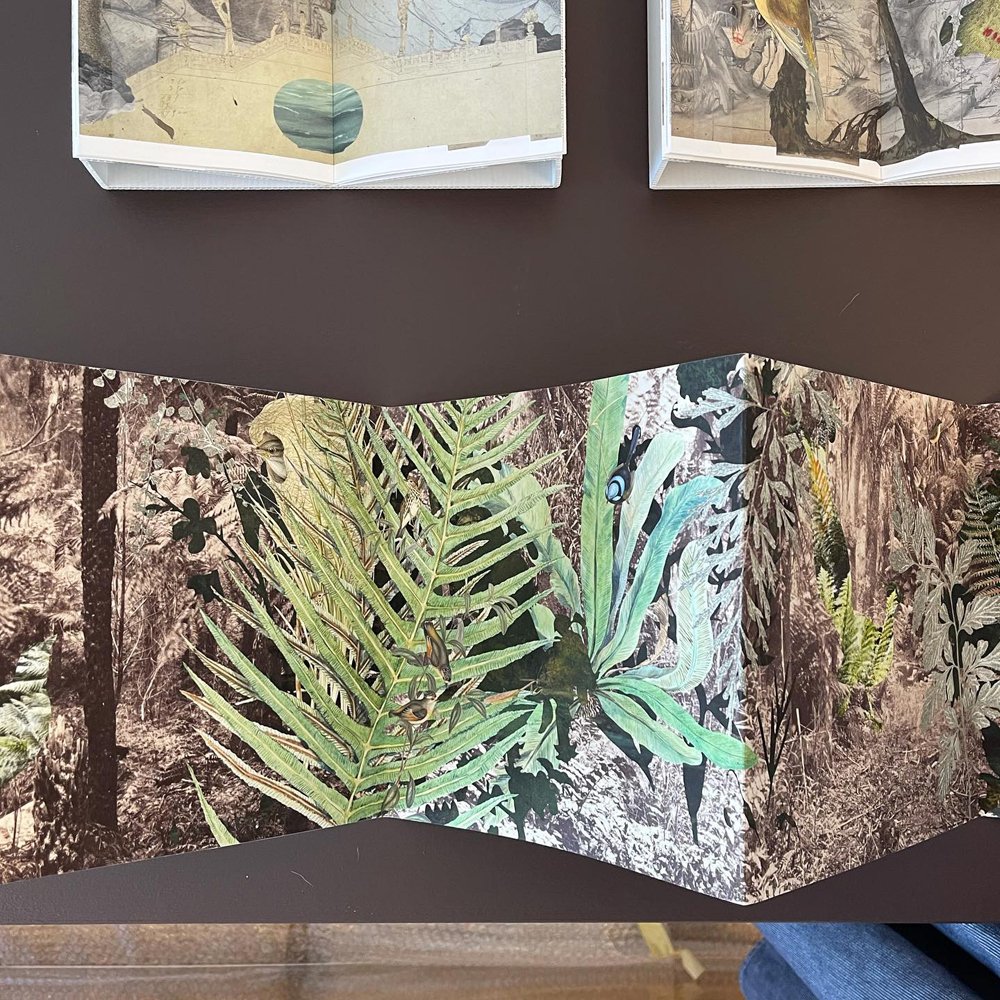

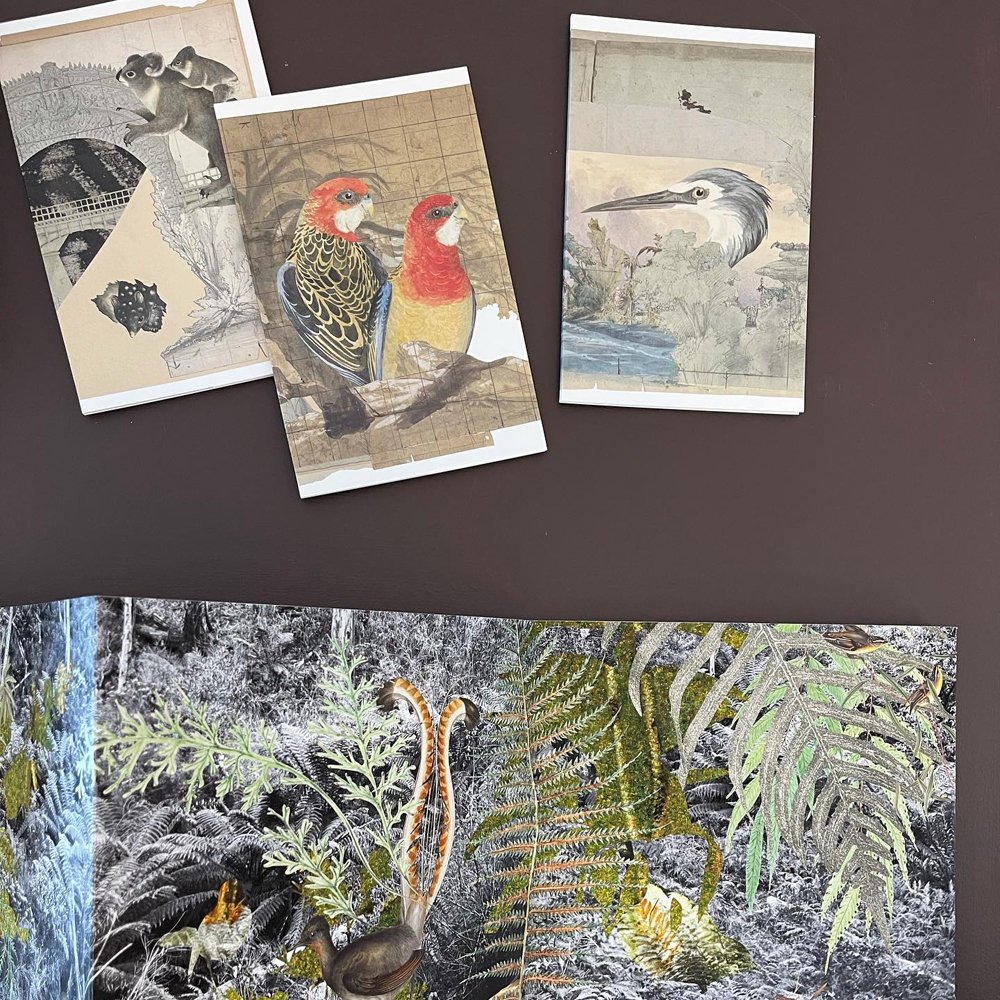

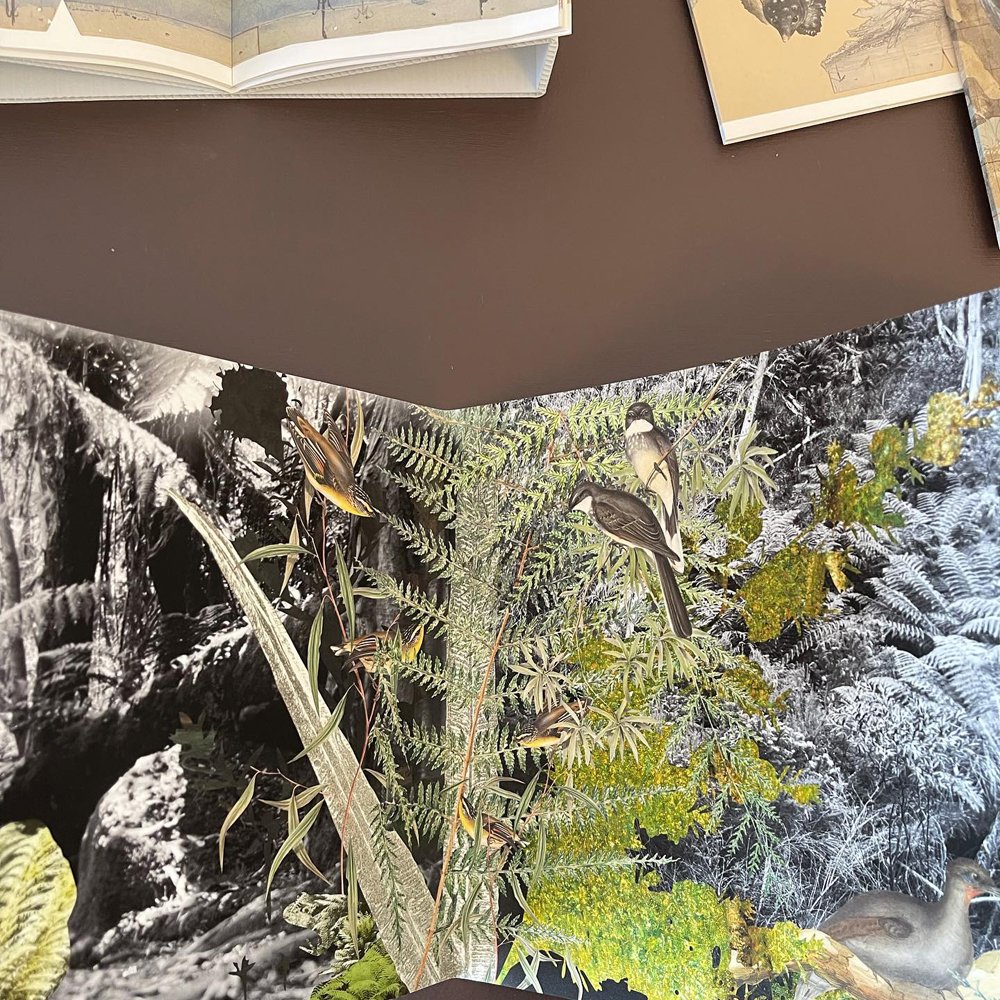

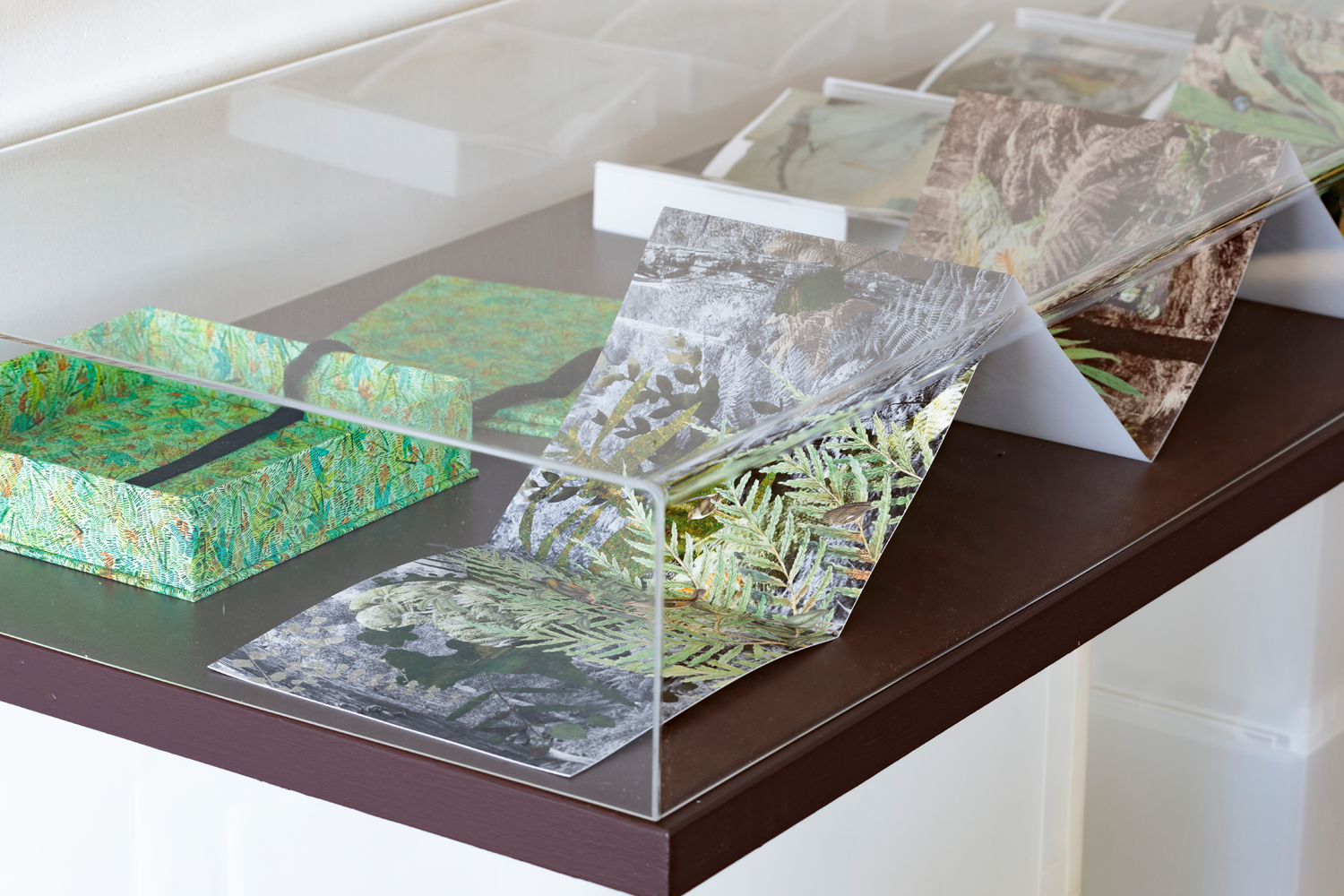

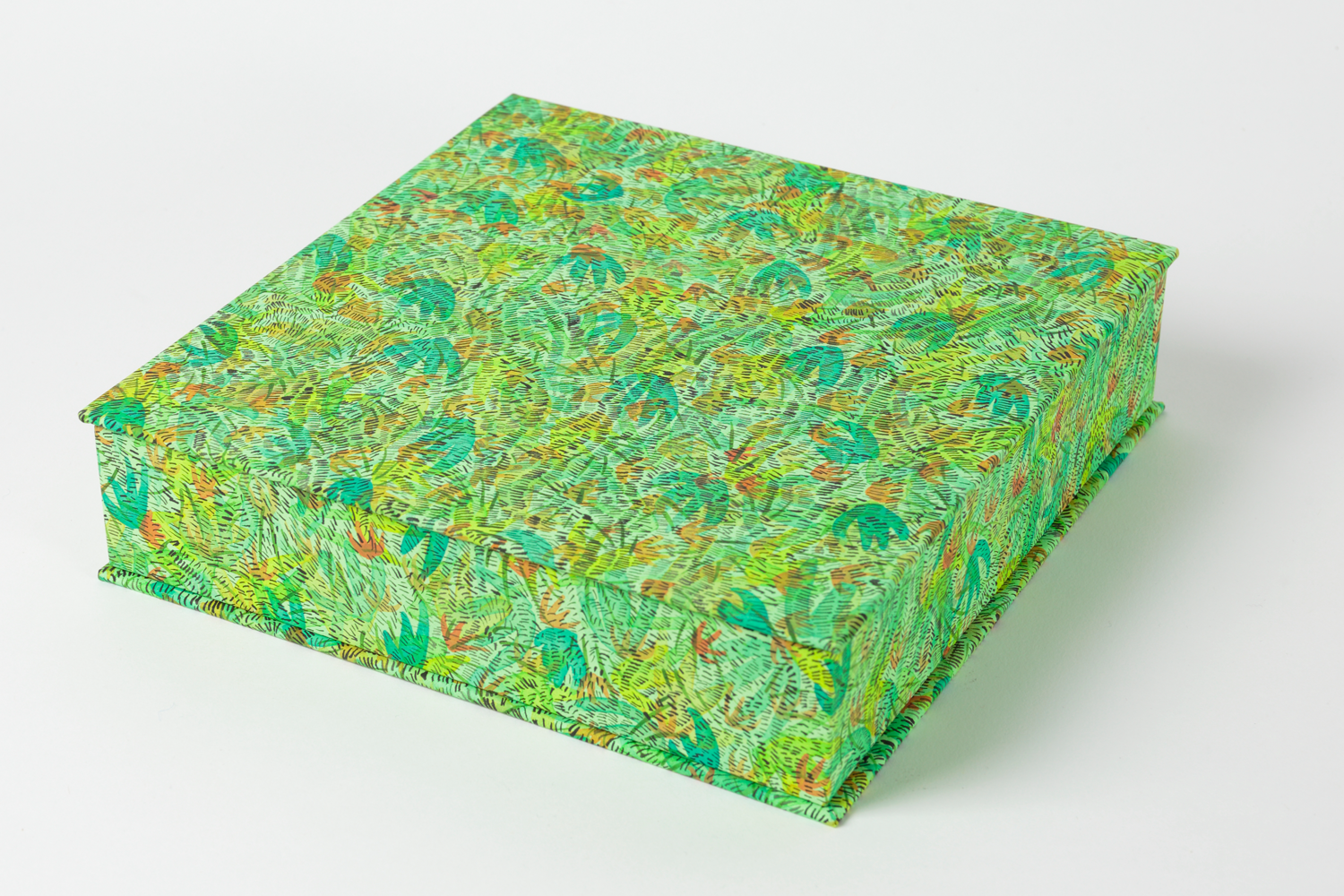

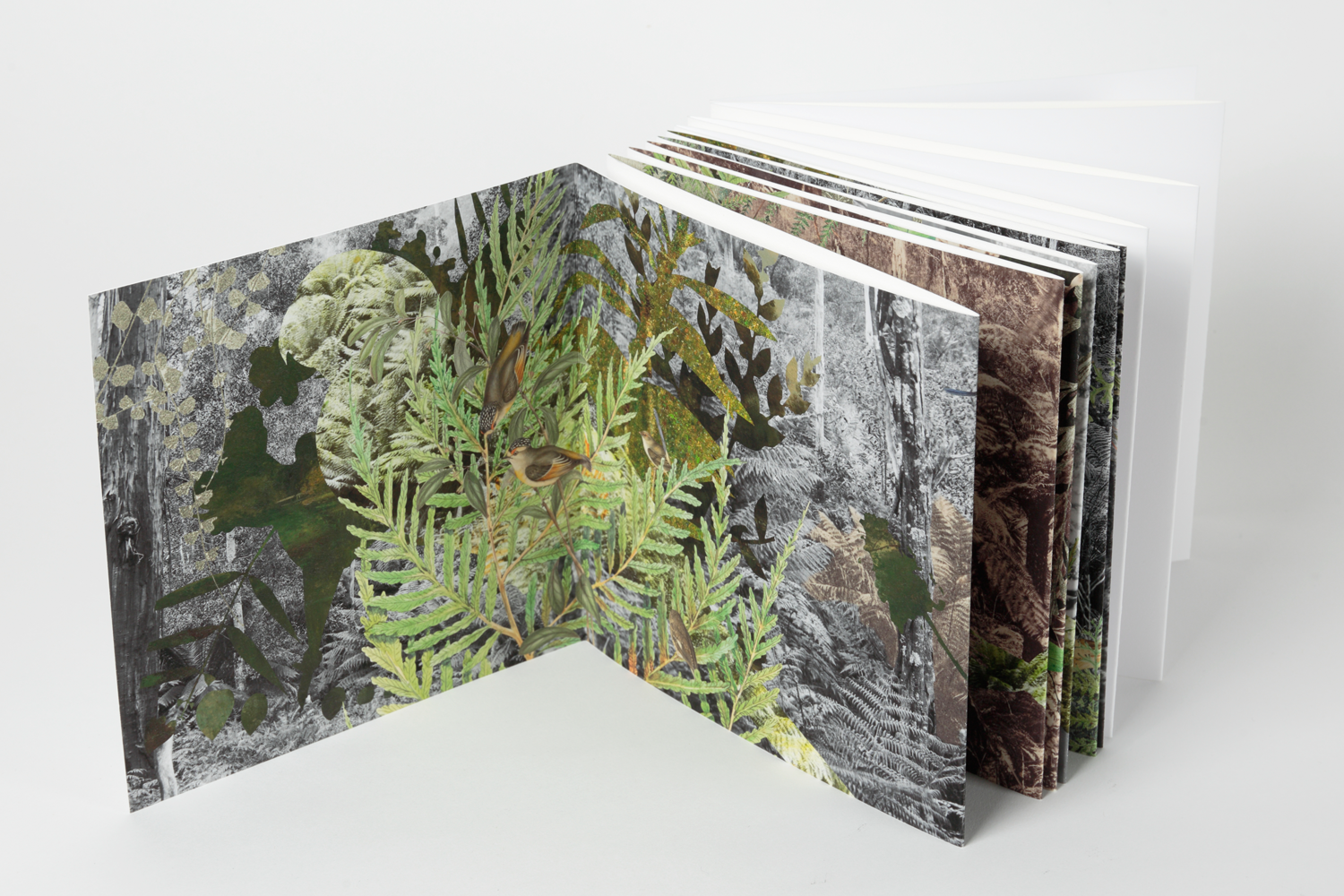

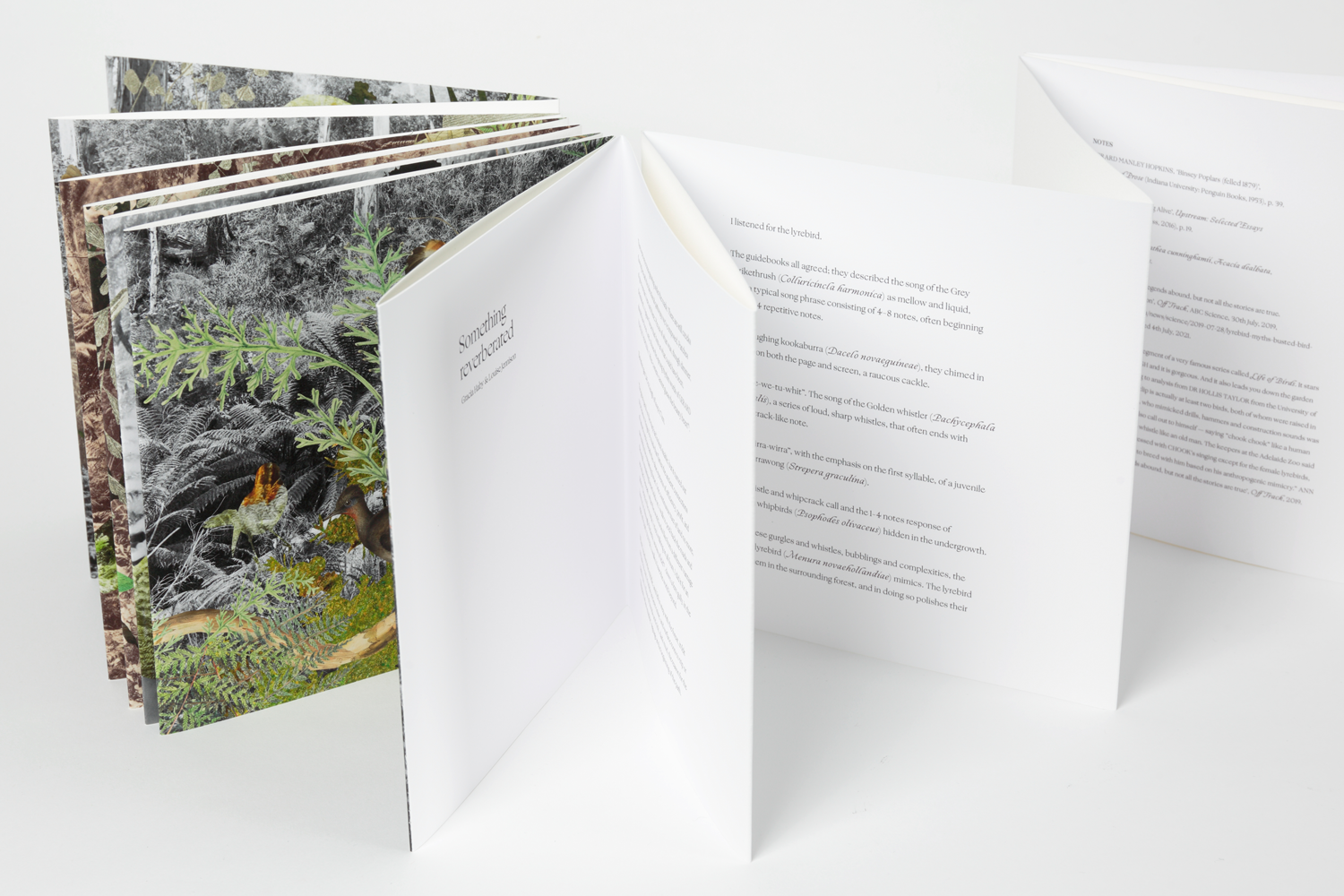

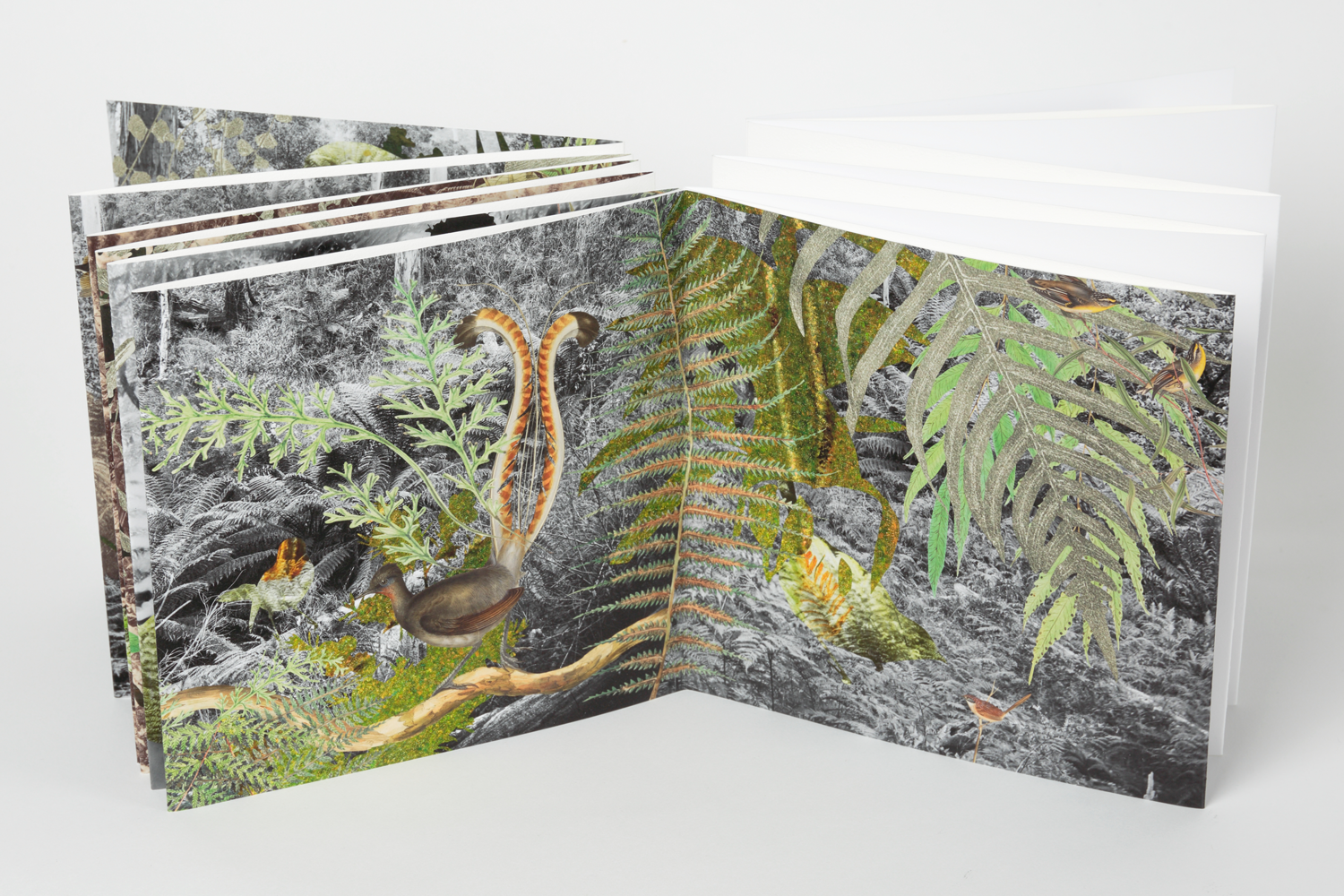

20 page concertina artists’ book, inkjet print on Canson Arches 88 310gsm, with accompanying narrative (by Gracia Haby), housed in a box (by Louise Jennison) with original watercolour cover on Saunders Waterford Aquarelle 300gsm white hot-press paper

Printed by Arten

Edition of 2

An artists’ book created especially for Biosphere, a group exhibition, curated by Felicity Spear.

The two editions of this artists’ book have been acquired by State Library Victoria and the State Library of NSW.

●

Biosphere — a sense of belonging

GRACIA HABY & LOUISE JENNISON, HARRY NANKIN, FELICITY SPEAR, DEBBIE SYMONS, ROSIE WEISS

WEDNESDAY 3RD OF NOVEMBER – SATURDAY 20TH OF NOVEMBER, 2021

AN EXHIBITION CURATED BY FELICITY SPEAR

STEPHEN MCLAUGHLAN GALLERY, ROOM 816, NICHOLAS BUILDING, 37 SWANSTON STREET, MELBOURNE

Enveloping the enormous mass of our planet is the Biosphere, a razor thin membrane supporting all life. Also called the ecosphere, it is the world-wide sum of all ecosystems. Essentially we are organisms within these systems, absolutely dependent on, and interdependent with other organisms. The interplay of the climatic system and biological diversity determine the effectiveness and resilience of this shield, the Earth’s biosphere, air, land, and water. Considering ourselves rulers of the biosphere however, we humans believe we are entitled to do anything to the rest of life that we wish.

Cumulative human culture has now become a significant global force, imposing an unprecedented impact on the operation of the Earth system. So much so that the current geological era has been proposed as the Anthropocene. Our planet’s 7.6 billion people represent just 0.01% of all living things, but since the dawn of civilisation humanity has caused the loss of 83% of all wild mammals and half of the plants. As human activity scales down Earth’s ecosystems and life becomes progressively less biodiverse, the biosphere becomes less resilient to changing circumstances and more difficult to maintain. It is in the self- interest of humanity to avoid pushing ecosystems or the entire Earth system across tipping points.

Nature’s surfaces are seductive. But beneath them lies a deep sense of pathos revealed in the destructive power of humanity. The artists represented in Biosphere — a sense of belonging, reflect on the wonder, complexity and the interconnected diversity of life within the biosphere. They reflect on the unfolding tragedy revealed in the fragility of life forms, indicators of ominous changes within ecosystems. They invite us to think about our sense of belonging within the natural world and the role which empathy might play in the future. Examples of empathy in other animals would suggest a long evolutionary history leading to this capacity in humans. The challenge of maintaining the resilience of the biosphere in the 21st century and beyond relies on our understanding that we are all connected. We belong to the biosphere. It does not belong to us.

Felicity Spear

﹏

RELATED LINKS,

WITH WINGS OUTSTRETCHED AND QUIVERING

MELBOURNE CITY OF LITERATURE WRITERS IN RESIDENCE, 2021

A HEMLINE OF SKY, FOREST, AND WATER THROUGH SMOKE

RELATED POSTS,

COLLECTION BOUND

HIDDEN IN THE UNDERGROWTH

FOR THE READING

SOMETHING REVERBERATED

COLLAPSE IN FOLDS LIKE THOSE OF A CONCERTINA

A HIGHLY THEATRICAL DISPLAY

LYREBIRDS AND BOWERBIRDS

WALK. FLY. BE.

ANOTHER COAT ON THE SHEETS OF PAPER WHICH WE WILL USE AS FABRIC

TRYING TO KEEP PACE WITH THE CALLS OF THE GALAHS AND THE BOWERBIRDS

Something reverberated

There were once trees growing under the roads. There are still creeks flowing beneath the directional pathways we’ve imposed. Patches of green remain, here and there. Pieces of what was, though dimmer, diminished. A jigsaw forest that hints at what could have been, should have been, and echoes the sprung rhythm words of Gerard Manley Hopkins, “After-comers cannot guess the beauty been”[i].

Elevation gain 243 m; length of loop 6.7 km.

The green patch on the map had looked sizable, but it turned out to be less so. Ringed by roads that flatten the ancient connections of nature’s web beneath the value systems of efficiency, profit, and ownership: the remaining forest. One continuous tract of land no more, the small, remaining forest holds on. I walk to peel back the roads and see what’s beneath, what the world looks like from a different vantage point. “Deep in the woods, I tried walking on all fours. I did it for an hour or so, through thickets, across a field, down to a cranberry bog”[ii], in the spirit of Mary Oliver. I walk to lose the world beyond.

When I reached the middle, and fell in step with the forest, it felt to have no end. It holds ancient noise, and surface roots to trip or catch you. A floor of fronds and rich, dark mud, the reason for the ‘Slippery when muddy’ signage at the beginning of the path. Here the world is different, if you let it be. An Eastern yellow robin (Eopsaltria australis), the ‘dawn harper’, flitted in the gloved green hush of Slender tree fern, Silver wattle, Small leaf bramble[iii]. When I loosened my focus, their movements alerted me to their presence all around me. The forest was inhabited by all sorts of birds, darting, calling, neatly punctuating sentence after sentence.

I saw the trees that had fallen in a recent storm lying long and flat against the earth. In this state of change, at their bright yellow ends, it was possible to count their inner rings. The smell of resin was strong. Next time I pass, they’ll be darker and damper and in the process of being claimed by lichens and mosses. Long logs at right angles to their kin, the Mountain ash, still reaching skyward.

I looked for display mounds of bare scratched earth. I looked at my own limbs, and wondered what musical instrument they might resemble if I were removed from this setting and seen lifeless elsewhere, just as European taxidermists once thought the tail feathers of the lyrebird formed the stringed instrument from which their English common name is derived. In the shape of the letter U? Why?

‘Berry lid’ is an anagram for ‘lyrebird’. Thoughts, like the forest tracks, lead to places I don’t always expect.

I listened for the lyrebird.

The guidebooks all agreed; they described the song of the Grey shrikethrush (Colluricincla harmonica) as mellow and liquid, with a typical song phrase consisting of 4–8 notes, often beginning with 2–4 repetitive notes.

The Laughing kookaburra (Dacelo novaeguineae), they chimed in unison on both the page and screen, a raucous cackle.

“We-we-we-tu-whit”. The song of the Golden whistler (Pachycephala pectoralis), a series of loud, sharp whistles, that often ends with a whipcrack-like note.

The “wirra-wirra”, with the emphasis on the first syllable, of a juvenile Pied currawong (Strepera graculina).

The whistle and whipcrack call and the 1–4 notes response of Eastern whipbirds (Psophodes olivaceus) hidden in the undergrowth.

All of these gurgles and whistles, bubblings and complexities, the Superb lyrebird (Menura novaehollandiae) mimics. The lyrebird hears them in the surrounding forest, and in doing so polishes their melody of mimicry. A forest garland of brilliant twittering they learned firstly from their parents, “like a genetically inherited trait”[iv], ensuring little change in the repertoire. Their song is one passed down the line. Their song is one learned and constantly finessed.

They can mimic the sound of car alarms, the chainsaws of foresters, the barks of canines, and the click-whirr shutter-snap of cameras too. Or rather, Chook[v] did at Adelaide Zoo and since went Sir David Attenborough viral. He hatched at the Healesville Sanctuary, and lived his less-wild life in captivity. As the panda sanctuary was built around him, he learned the call of the hammer and drill. A lyrebird is a superb mimic. But I needn’t worry that they’ll add my sound to their composition next time I pass through the forest[vi]. Their green reflection, in this regard, is complete without my intrusion. They can, after all, replicate “the chuckle of a flock of Crimson Parrots”[vii].

Manna gum, Blackwood, Tree everlasting[viii], teeming. The forest was bordered by roads, but it was still ancient, deep down, in the parts we allowed to remain.

When we hew or delve:

After-comers cannot guess the beauty been.

Notes:

[i] Gerard Manley Hopkins, ‘Binsey Poplars (felled 1879)’, Poems and Prose (Indiana University: Penguin Books, 1953), p. 39.

[ii] Mary Oliver, ‘Staying Alive’, Upstream: Selected Essays (New York: Penguin Press, 2016), p. 19.

[iii] Common names for Cyathea cunninghamii, Acacia dealbata, and Rubus parvifolius.

[iv] Ann Jones, ‘Lyrebird legends abound, but not all the stories are true. Let’s sort fact from fiction’, Off Track, ABC Science, 30th July, 2019, https://www.abc.net.au/news/science/2019-07-28/lyrebird-myths-busted-bird-calls/11342208, accessed 4th July, 2021.

[v] “This is a very famous segment of a very famous series called Life of Birds. It stars David Attenborough and it is gorgeous. And it also leads you down the garden path a little, using the magic of television. According to analysis from Dr Hollis Taylor from the University of Sydney, the bird in this clip is actually at least two birds, both of whom were raised in captivity. The main one, who mimicked drills, hammers and construction sounds was Chook…. [He] would also call out to himself — saying “chook chook” like a human might say, and he’d also whistle like an old man. The keepers at the Adelaide Zoo said everyone was very impressed with Chook’s singing ... except for the female lyrebirds, who never once agreed to breed with him based on his anthropogenic mimicry.” Ann Jones, ‘Lyrebird legends abound, but not all the stories are true’, Off Track, 2019.

[vi] “To observe him you must study his movements, learn of his runways, the position of his dancing and scratching mounds, and you must learn to crawl on the ground like a beetle and wriggle along like a snake; but above all you must have plenty of time and patience.” James R. Kinghorn, ‘The Lyre Bird at Home: A New Gallery Group for the Museum’, The Australian Museum Magazine, Volume 4, No. 1, January–March 1930, pp. 2–7.

[vii] From a listing on Antipodean Books, New York, a 1932 recording, The History and Song of the Lyrebird, Australia’s Greatest Songster is described as “‘....the first record of the Lyre Bird ever made in the native haunts of Australia’s premier songster’. Recorded by Herschells Pty Ltd. Sound Picture Producers Melbourne in the Sherbrooke Forest, Victoria, Australia under the supervision of Mr. Ray Littlejohns, member of Royal Australasian Ornithologists Union. Dialogue by Mr. Alfred L. Samuel. Record in fine condition in very good printed yellow/orange jacket, illustrated with a drawing of a lyrebird. From the wrapper — ‘His mimicry is almost uncanny and in addition to his wonderful repertoire you will hear above the roar of the wind in the forest, perfect imitations of — the Butcher Bird, the Kookaburra, the Australian Thrush, the Whip Bird, the chuckle of a flock of Crimson Parrots, the Pilot bird, the Black Cockatoo, the Honeyeater.... You will also distinguish what appears to sound like a man hammering a fence, a water pump in action, a Dog barking the warning cry of a White Cockatoo, the chuckle of a domestic Fowl and a man whistling for his Dog.’ From the library of Theodora Cope, one of the founders of the Cornell Ornithology Laboratory, who photographed birds throughout the Southern Hemisphere with her father Francis Cope in the late 1920s. Jacket with some corner bends otherwise very good.”

[viii] Common names for Eucalyptus viminalis, Acacia melanoxylon, and Ozothamnus ferrugineus.

References:

Jennifer Ackerman, The Bird Way: a look at how birds talk, work, play, parent, and think (Scribe Publications: Brunswick, Victoria, 2020)

Walter E. Boles, The Robins and flycatchers of Australia (Angus & Robertson Publishers: Sydney, 1988)

Alexander H. Chisholm, Mateship with Birds (Scribe Publications: Brunswick, Victoria, 2013)

Nicholas Day and Ken Simpson, Field Guide to the birds of Australia, 8th edition (Penguin Books Australia: Camberwell, Victoria, 2019)

Peter J. Higgins, John M. Peter, and William K. Steele, Handbook of Australian, New Zealand and Antarctic Birds, Volume 5, ‘Tyrant-flycatchers to Chats’ (Oxford University Press: Melbourne, 2001)

Ronald Strahan, Cuckoos, Nightbirds and Kingfishers of Australia (Angus & Robertson Publishers: Sydney, 1994)

Peter Wohlleben, The Inner Life of Animals: Surprising Observations of a Hidden World, trans. Jane Billinghurst (Vintage: London, 2018)

Earlier, as part of our Melbourne City of Literature’s writers in residence, from 9am until 9pm, on Friday the 28th of May, 2021, we shared how our lockdown 5km radius walks inspired the making of this artists’ book and led us to become wildlife carers, further greening our connection to nature. We revealed the making of this artists’ book, from every dash to splice, on our Reels, and though the collage and accompanying words feature the Eastern Sherbrooke Forest, you, the reader, are invited to feel the forest on the page to be one you are personally connected to and feel you know, leaf by twig. Where we hear a lyrebird, perhaps you may hear something else.

Biosphere — a sense of belonging

Penelope Gebhardt

February 2022

Biosphere — a sense of belonging comprises six artists whose practices share an empathy and concern with the natural world and the impacts of climate change. In this exhibition their work spins a sobering story of destruction and loss whilst also suggesting tentative threads of hope.

The symbiosis between living organisms and their environment creates the biosphere. The rapidly altering shape and patterns of the Earth’s living systems through human-induced climate change has put the Earth as we know it in peril.

By definition ‘belonging’ refers to a secure relationship, an affinity. The primary meaning of ‘belong’ however, is to be the property or possession (of). This duality can represent different philosophies of being. When applied to the biosphere, the first meaning implies interconnection and care. The second represents human exceptionalism and the systemic proprietorial principles of colonisation, the root cause of climate change.

Rosie Weiss’s works on paper reference Gippsland after the devastating bushfires of 2019/20. The artist recalls, ‘It was overwhelming to find places…where no thing stirred, places of absolute silence, without a single green shoot, insect or bird.’[1] A drawing of charcoal debris on a hot-pink background is like a siren or a call to arms. The symbols evoke shorthand messages of care – a kiss and hug at the end of a message which may be offered as a heartfelt gesture or a hackneyed one. The title Do you still love me? (Asked the earth) is a question of care and ultimately, of belonging. It implies that there was once an affinity that is now in doubt. On the opposite wall are detailed drawings of couch grass on metallic ink titled Breath Fracture and Do you still love me? Asked the earth (couch). Listed as the second most significant weed in the world[2], couch is highly invasive and causes widespread degradation of native species’ health and diversity. There is irony in the artist’s vision of couch being the lone survivor in the wake of an environmental catastrophe. On approach, light reflects on the drawings’ metallic surfaces, withholding sections of the image, suggesting truths we cannot see or perhaps refuse to see.

A cluster of forms suspended from a tree branch emits bird calls — a shimmer of aural movement in the quiet space. Debbie Symons references the nest of the Yellow-rumped Cacique Cacicus cela in her installation, Sing. The artist encountered the bird on a residency in Manaus, Brazil in 2018. Symons observed the pendulous forms of their nests ‘hanging above waters containing predators that are both mysterious and threatening’[3] Symons has woven nests in imitation of the Cacique, but instead of using endemic Amazonian fibers, Symons’ are constructed from African oil palm fronds. Oil palm is cultivated on an industrial scale, resulting in rapid deforestation across some of the world’s most biodiverse hotspots including the Amazon Rain Forest. Secreted in Symons’ nests are speakers releasing a recording of the Cacique’s song. This work raises ideas concerning ecocide, species adaptability and the liminal space between belonging and extinction.

On the back wall looms Felicity Spear’s larger than life drawing Darkness falls, referencing a black geometrid Melanodes anthracitaria. Due to its colour, the moth’s name derives from ‘anthracite’, a pure form of coal. With charcoal as her medium, Spear draws a connection between the moth and the moth’s namesake - a fossil fuel that when burnt is the single largest contributor to climate change[4]. The moth lies flat, affixed to the wall, cloaked in soft powdery tonal patterns resembling topography. Moths are nocturnal creatures, millions of years older than butterflies. Their fragility and transience are potent reminders of the brevity of life. The moth is oriented towards the luminous moons hanging on the adjoining wall.

The moon is, among a great many things, a sacred symbol, keeper of tides, weather influencer, and signaller to life on Earth. In On reflection — ebb and flow, Spear presents two digital prints of a full moon reflected in a dam. The movement of life in the water agitates the surface, creating ripples that act as a second lens. Suspended like an ovum, this distinctly biological impression of the moon invites ideas of human and nonhuman reproduction, such as the spawning of the Great Barrier Reef when the corals release their egg and sperm bundles after a full moon. The moon is an almost untouched natural environment that in dark moments both literal and metaphorical can be a potent reminder that perhaps not all is lost.

Gracia Haby and Louise Jennison have collaborated artistically for over twenty years. Their artists’ book, Something reverberated was created especially for this project, and grew from a deepening engagement with the natural world that was inspired by walks in remnant forest in and near Melbourne. These encounters generated speculation about the ecologies of place predating colonisation, and the subsequent impacts of land theft and capitalism. Encompassing some 240 layers of collaged elements referenced from the archives of the State Libraries of Victoria and New South Wales, the concertina forest extends and contracts in its book form, creating layers of memory and imagined histories. In sepia tones and black and white, the imagery suggests echoes of past ecologies, traces of which may lie sleeping still, waiting under the roads. ‘The forest was bordered by roads, but it was still ancient, deep down, in the parts we [colonial settlers] allowed to remain.’[5] Meanwhile, fragments of coloured foliage and bird life speak to the still-living bush, the remnants that remain. Perhaps the Something [that] reverberated is the resonance of deep time and knowledge, that life on Earth will go on irrespective of human presence.

Harry Nankin’s pictures tell a story of climate change in Australia’s alpine region. Hung in three tiers, the works span twenty-six years. The central panel, Moth liturgy, is a shadowgram of Bogong Moths Agrotis infusa. Created in 2011, the moths landed on exposed photographic film near their migratory destination at Mount Buffalo, leaving behind their shadows. Nankin enlarged the image and infused it with colour, making the moths more visible to the human eye. The Bogong Moth is known for its astonishing ability to navigate using celestial optical cues and an internal magnetic compass. Each spring this keystone species travels hundreds of kilometers from the lowlands to hibernate in the alpine caves. Above and beneath the moth image are prints of the surrounding alpine landscape. Winter light, Mount Jaithmathang, a large format photograph, depicts the mountain in 1995; the scrub is encased in snow, and alpine peaks rise mythically in the background. In contrast, a series of smaller black and white images titled After the fire document the landscape in the aftermath of the 2019/20 bushfires. The forms and textures of these images are stark — charred sticks and branches appear petrified alongside granite boulders, like exposed bones in the landscape. The Bogong Moth once migrated in great numbers, pollinating plants, and providing an important food source for many species. In 2021 it was declared endangered. As the Earth’s climate changes, beings such as the Bogong Moth struggle to survive. Species extinction degrades the biosphere, inciting a rapid cascade effect on the ecosystems upon which we all depend.

The sphere motif recurs throughout the exhibition. Rich with symbolism, it evokes coming full circle, in the sense of a life cycle. It can also be a void, a nullifying of existence. Or the source itself, a place of mystery, new beginnings, and hope. Scientist and author Robin Wall Kimmerer writes in her celebrated book Braiding Sweet Grass, ‘She [sweet grass] reminded me that it is not the land that has been broken, but our relationship to it.’[6] The survival of the biosphere as we know it depends on the well-being of the networks of mutual care in which we exist. Weighted with sorrow and precarity, the works in this exhibition embody an affinity with the natural world that highlights a critical need to reflect on human belonging as part of a larger network of care.

[1] Biosphere — a sense of belonging, exhibition catalogue, 2021

[2] https://keys.lucidcentral.org/keys/v3/eafrinet/weeds/key/weeds/Media/Html/Cynodon_dactylon_(Couch_Gr ass).htm accessed 1 February 2022

[3] https://debbiesymons.com.au/sing-2020-21/ accessed 1 February 2022

[4] https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/global-greenhouse-gas-emissions-data accessed 15 February 2022

[5] https://gracialouise.com/works/something-reverberated accessed 28 January 2022

[6] Robin Wall Kimmerer (Citizen of the Potawatomi Nation), ‘Braiding Sweet Grass’, (Penguin, 2003), 336.