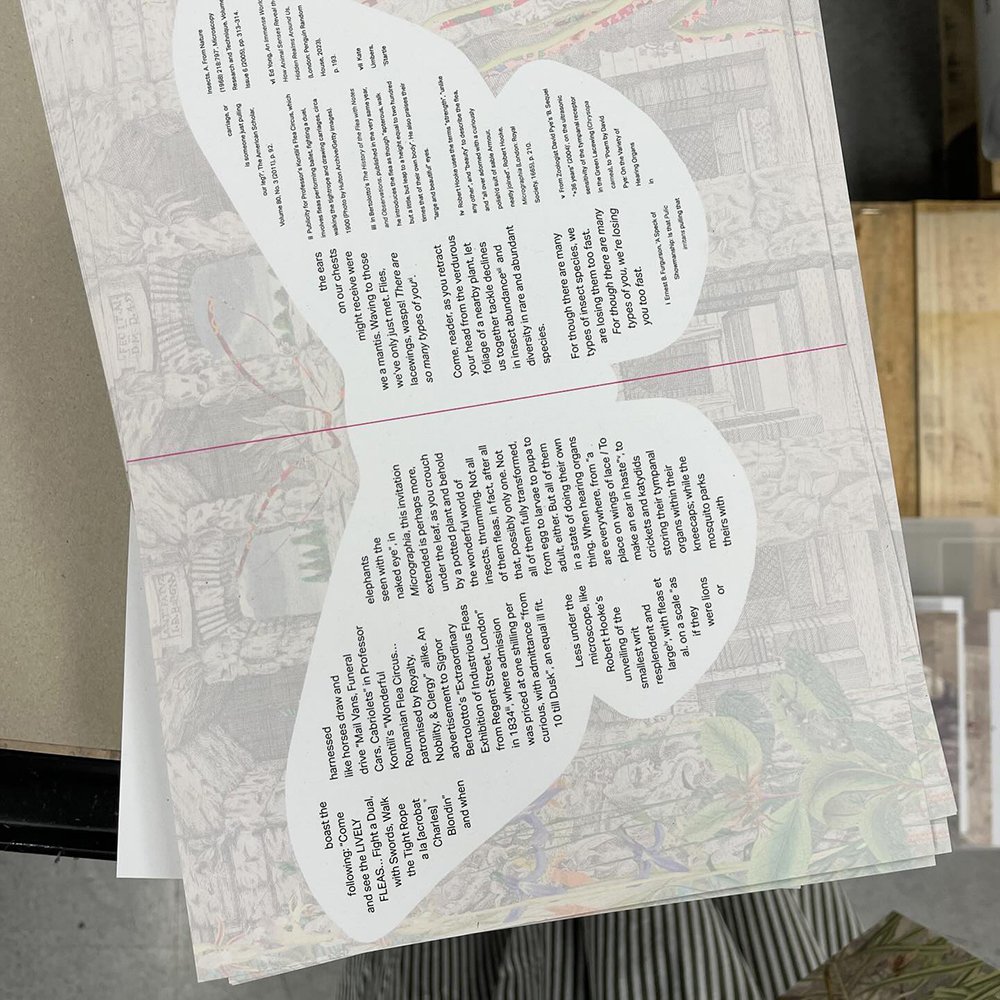

BILATERAL SYMMETRY

This invitation extended is perhaps more, under the leaf, as you crouch by a potted plant and behold the wonderful world of insects, thrumming.

Components within Bilateral Symmetry

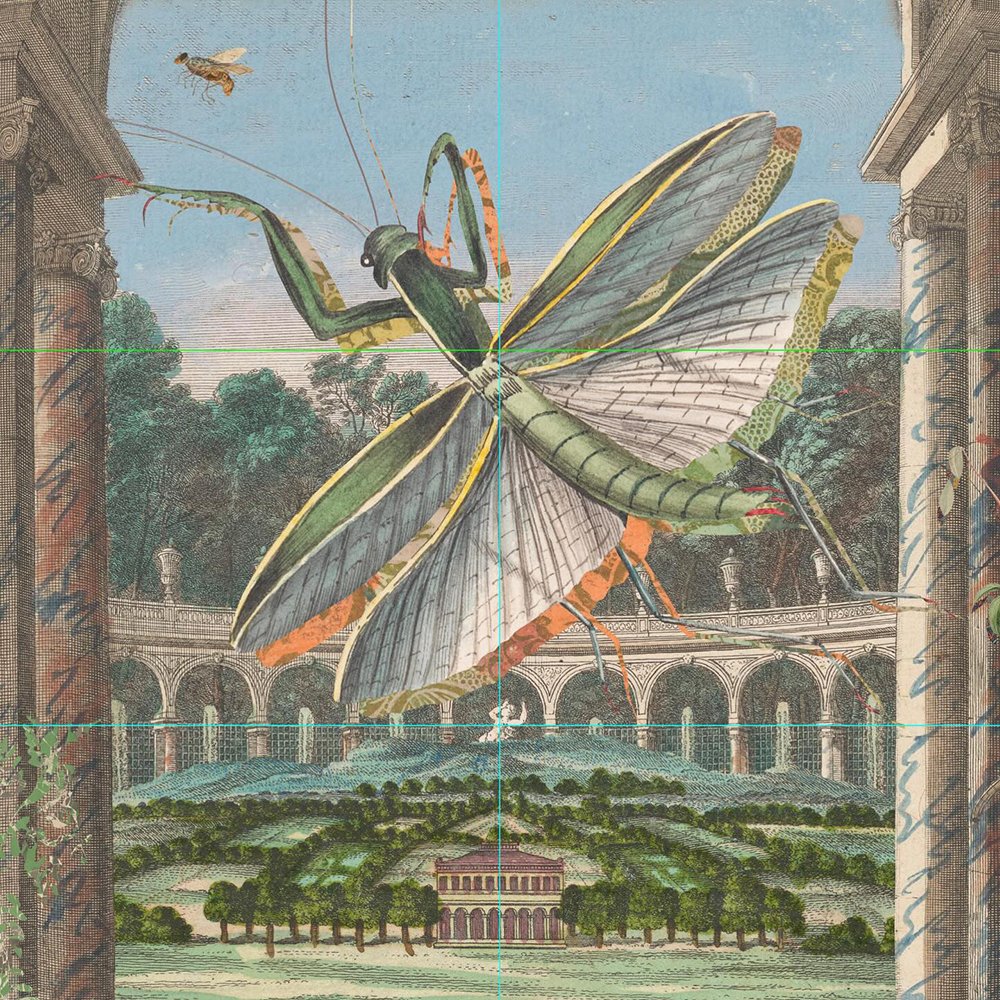

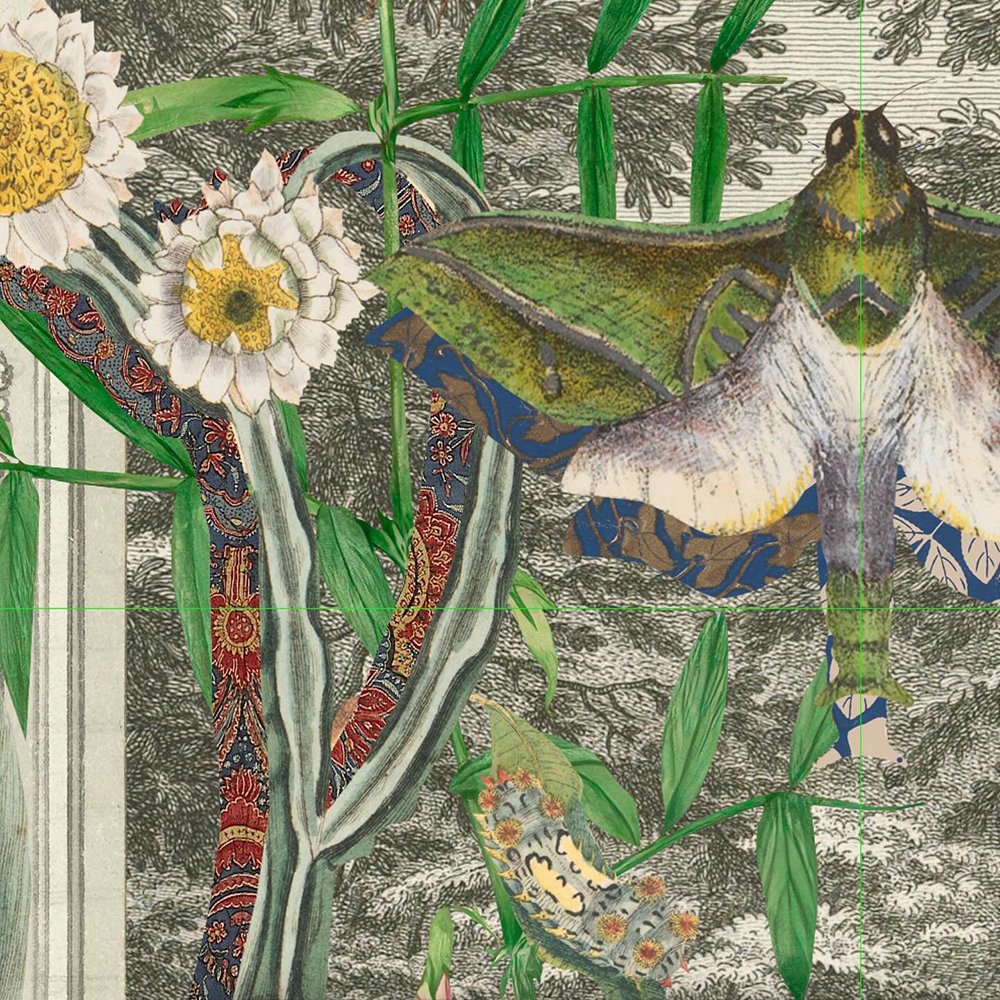

Gloriously Wild, The Lost Island, 2024

Gracia Haby & Louise Jennison

Bilateral Symmetry

2024

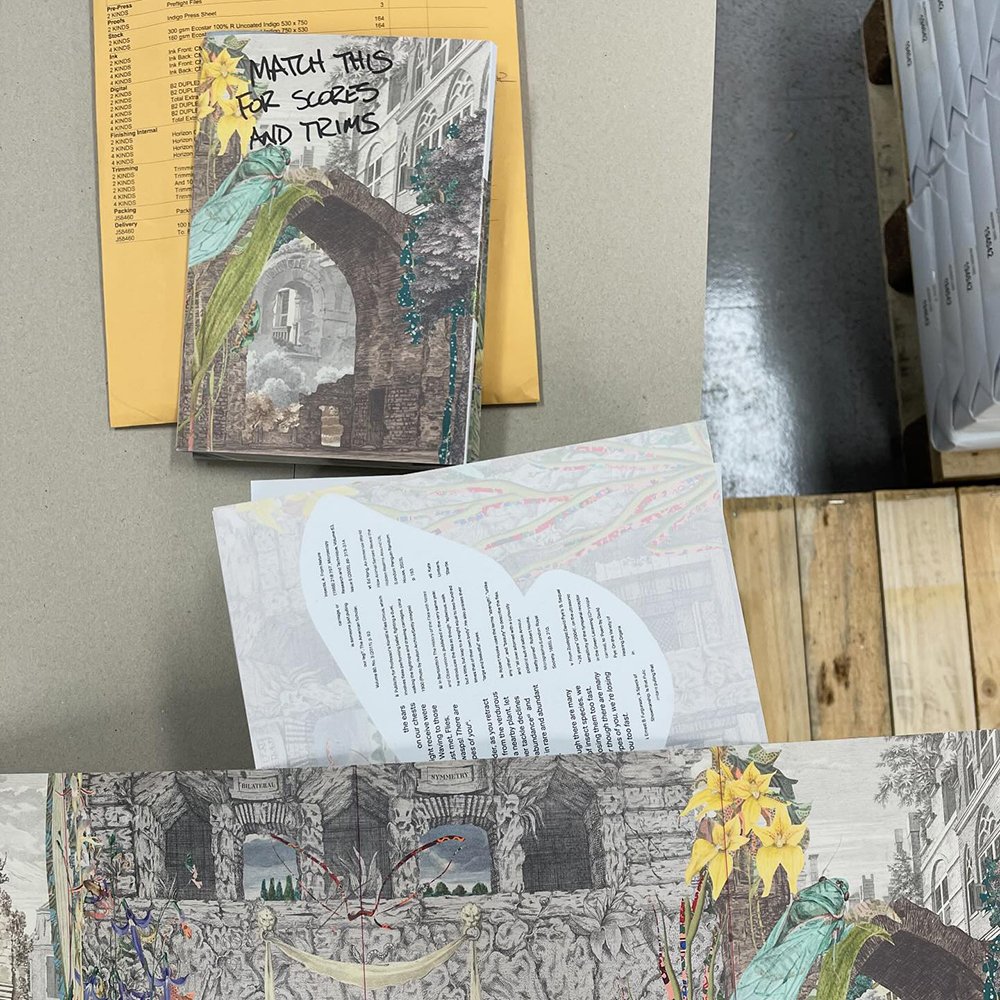

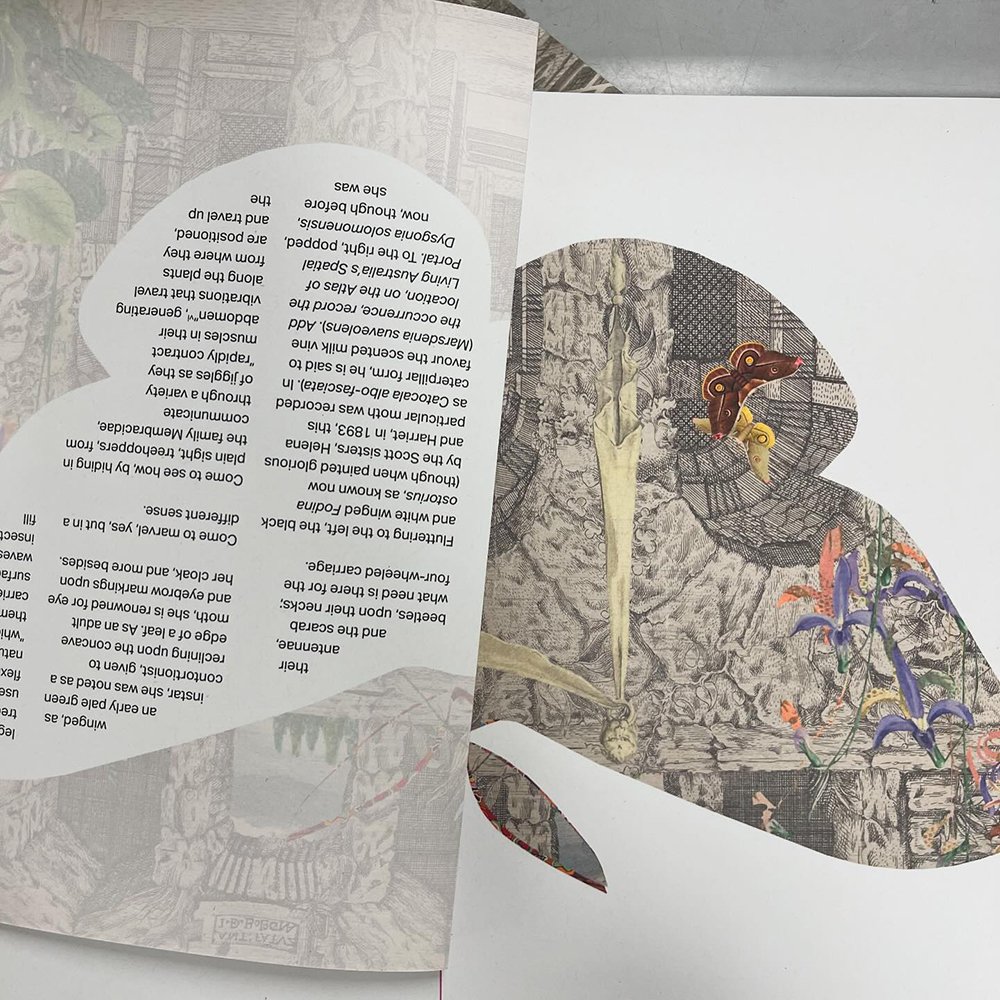

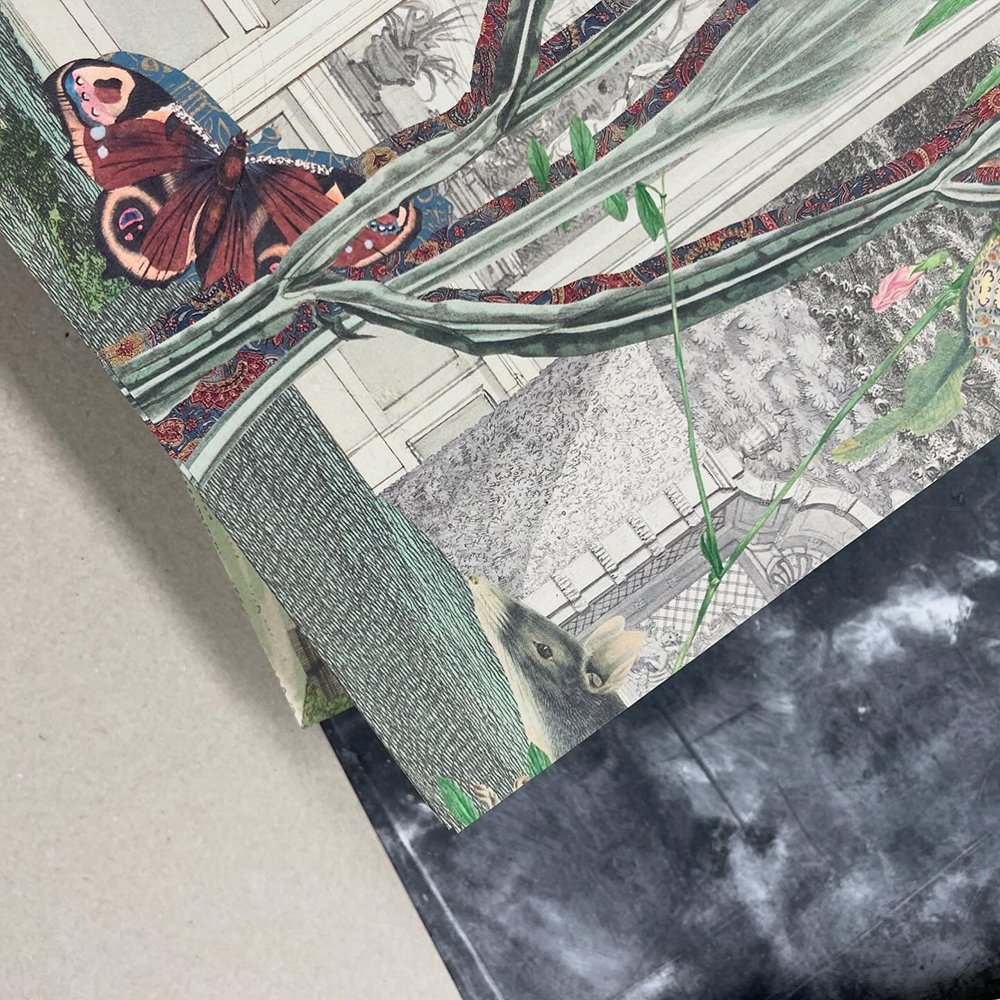

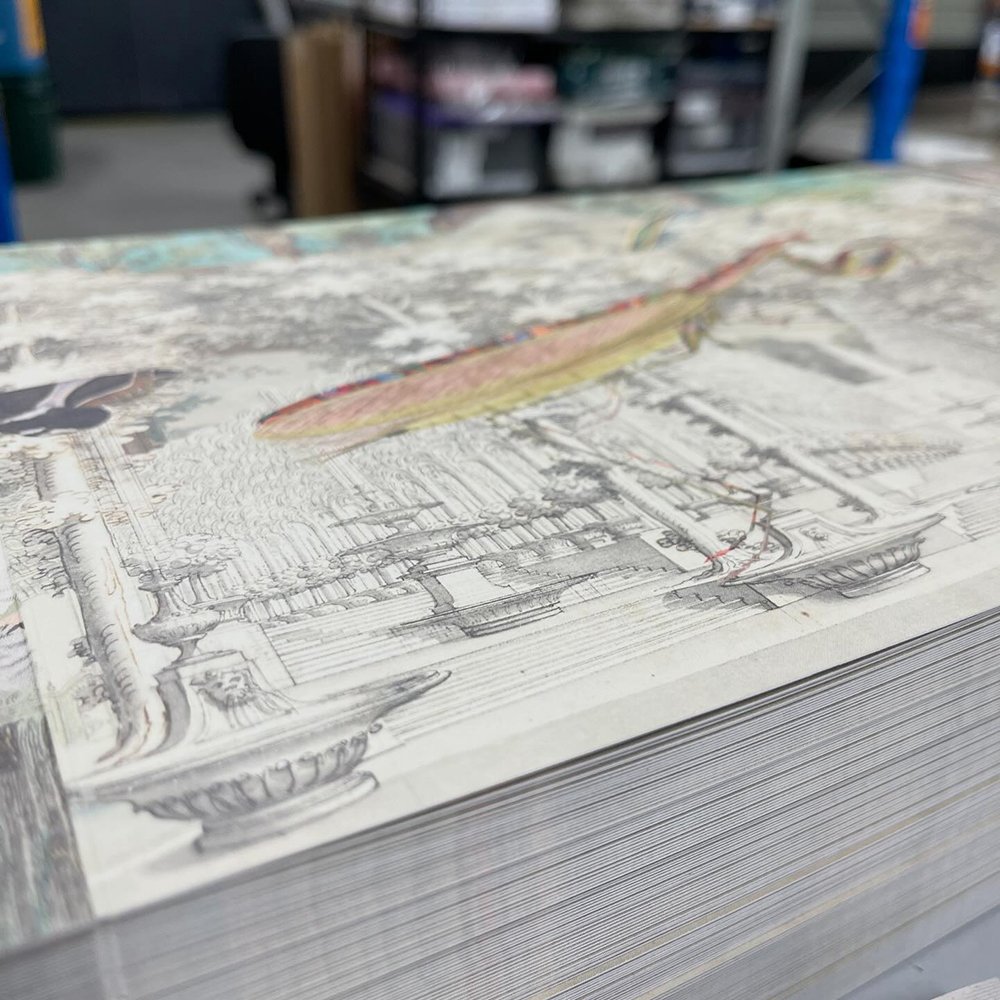

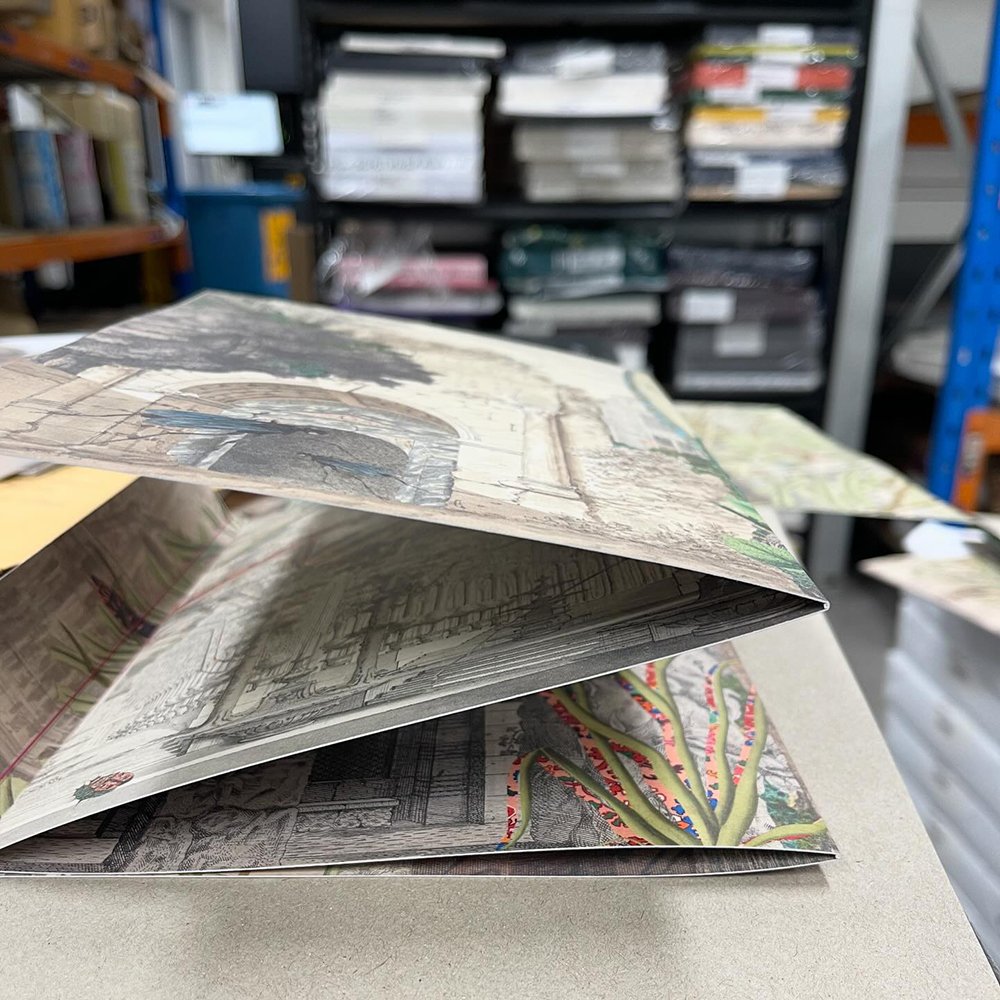

24 page barn fold, pamphlet stitched, artists’ book, with pop up components and narrative (by Gracia Haby), Indigo Digital CMYK on 160gsm ecoStar + 100% Recycled Uncoated, with cover, Indigo Digital CMYK on 300gsm ecoStar + 100% Recycled Uncoated

Printed by Bambra

Bound by Gracia Haby & Louise Jennison, with hand-cut elements

Edition of 100

Bilateral Symmetry was released at this year’s tenth Melbourne Art Book Fair, NGV International (Thursday 23rd of May – Sunday 26th of May, 2024).

Editions of Bilateral Symmetry have been acquired by the Melbourne Museum, the University of Melbourne’s Baillieu Library, State Library Victoria, State Library of NSW, Research Library and Archive of the Art Gallery of NSW, State Library of Queensland, and University of West England (UK).

An edition of Bilateral Symmetry will also be exhibited as part of Plant Life (Saturday 24th of January – Sunday 1st of March, 2026), curated by Rhett D’Costa, Magali Gentris, and Jason Waterhouse, at Stockroom Kyneton.

You can order a copy through our online store, and read but a taste below, or in full treehopper glory in Woolly Bears! Needle Miners! on Marginalia.

●

A miniature lock and key, forged of iron, steel, and brass, gave rise to the flea circus boom, or so the tale goes, when Mark Scalliot, a 16th Century smithy, fashioned to his lock and key, a fine chain of 43 links which he in turn fastened “about the neck of a flea, which drew them all with ease. All these together, lock and key, chain and flea, weighed only one grain and a half.” Created “for exhibition of trial and skill”, it coincidentally highlighted the finesse of a single flea (Pulex irritans), and so we have orchestrated, in our own exhibition of skill with scissors and files, a theatre for insects. Though this time around, our fellow exhibitors, the insects, all, momentarily pressed within our artists’ book, Bilateral symmetry, are untethered and unglued upon the unfolding paper stage. And all weighing no more, it is estimated, than 1662 grains of gold, once bound in book form.

Here, you’ll find no tiny carriages in a show of horological prowess. Not for them an ivory “landau with figures of six horses attached to it — a coachman on the box, a dog between his legs, four persons inside, two footmen behind, and a postillion on the fore horse, all of which were drawn by a single flea[i]”, like that of watchmaker Sobieski Boverick, sparked some two centuries after Scalliot. The handbill, were there one to read, could not, would not, boast the following: “Come and see the LIVELY FLEAS… Fight a Dual, with Swords, Walk the Tight Rope a la [acrobat Charles] Blondin” and when harnessed like horses draw and drive “Mail Vans, Funeral Cars, Cabriolets” in Professor Kontili’s “Wonderful Roumanian Flea Circus… patronised by Royalty, Nobility, & Clergy”[ii] alike. An advertisement to Signor Bertolotto’s “Extraordinary Exhibition of Industrious Fleas from Regent Street, London” in 1834[iii], where admission was priced at one shilling per curious, with admittance “from 10 till Dusk”, an equal ill fit.

Less under the microscope, like Robert Hooke’s unveiling of the smallest writ resplendent and large[iv], with fleas et al. on a scale “as if they were lions or elephants seen with the naked eye”, in Micrographia, this invitation extended is perhaps more, under the leaf, as you crouch by a potted plant and behold the wonderful world of insects, thrumming. Not all of them fleas, in fact, after all that, possibly only one. Not all of them fully transformed, from egg to larvae to pupa to adult, either. But all of them in a state of doing their own thing. When hearing organs are everywhere, from “a place on wings of lace / To make an ear in haste”[v], to crickets and katydids storing their tympanal organs within their kneecaps; while the mosquito parks theirs with their antennae, and the scarab beetles, upon their necks; what need is there for the four-wheeled carriage.

[i] Ernest B. Furgurson, ‘A Speck of Showmanship: Is that Pulic irritans pulling that carriage, or is someone just pulling our leg?’, The American Scholar, Volume 80, No. 3 (2011), p. 92.

[ii] Publicity for Professor's Kontili's Flea Circus, which involves fleas performing ballet, fighting a duel, walking the tightrope and drawing carriages, circa 1900 (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images).

[iii] In Louis Bertolotto’s The History of the Flea with Notes and Observations, published in the very same year, he introduces the flea as though “apterous, walk but a little, but leap to a height equal to two hundred times that of their own body”. He also praises their “large and beautiful” eyes.

[iv] Robert Hooke uses the terms “strength”, “unlike any other”, and “beauty” to describe the flea, and “all over adorned with a curiously polish’d suit of sable Armour, neatly joined”. Robert Hooke, Micrographia (London: Royal Society, 1665), p. 210.

[v] From Zoologist David Pye’s ‘B. Sequel “+36 years” (2004)’, on the ultrasonic sensitivity of the tympanal receptor in the Green Lacewing (Chrysopa carnea), to ‘Poem by David Pye: On the Variety of Hearing Organs in Insects, A. From Nature (1968) 218:797’, Microscopy Research and Technique, Volume 63, Issue 6 (2005), pp. 313–314.

﹏

RELATED LINKS,

PLANT LIFE, 2026

NGV MELBOURNE ART BOOK FAIR 2024

RESTORING CORRIDORS COLLAGE WORKSHOP

RELATED POSTS,

LOOK CLOSER

MARVELS, WINGED AND TAILED

MICROSCOPIC RECREATIONS

UNDERSTORY

BOOK FAIR HIGH SPIRITS

WOOLLY BEARS! NEEDLE MINERS!

THERE BE BEETLES, AND THERE BE POSSUMS

TAKING FORM

TINY BUT WILD

WILDLINGS

FROM DREAMWEAVER

Bilateral Symmetry features elements from several collections, including the following from State Library of New South Wales.

Flying Squirrel (Plate 6)

Ringtail opossum (Ringtail possum) (Plate 22)

and a Dragonfly (Plate 28) from:

Natural history and botanical drawings, ca. 1849-1872

[attributed to Louisa Atkinson (1834–1872)]

Part of Atkinson and Cosh family pictorial material, ca. 1842–1973

60 drawings — pencil, ink, wash, and watercolour drawings

3 photographs

Mrs Elizabeth Gould collection of drawings of Australian plants, flowers and foliage, 1838–1842

Elizabeth Gould (1804–1841)

76 watercolour and pencil drawings (hinged into 3 booklets) — 61 x 43.5 cm

Phascogale penicillata [Brush-tailed marsupial mouse] / G. Krefft

[Native rat, possibly brush-tailed rabbit-rat] / G. Krefft, 1858

Hapalotis Arboricola (Macleay) [Type of hopping mouse or rabbit-rat. Arbricola = plant] / G. Krefft, 1861 from:

Series 02: Gerard Krefft album of watercolour drawings, ca. 1857-1858, 1861, 1866

Gerard Krefft (1830–1881)

35 watercolours — 49 x 37 cm or smaller

1 drawing — pencil

Lathyrus and other specimens from:

Botanical sketches of Australian plants, 1803–1806

John Lewin (1770–1819)

265 drawings, on 257 sheets, hinged into booklets — 38–38.5 cm.- 25–28 cm. approx. — watercolour, pen, ink and pencil

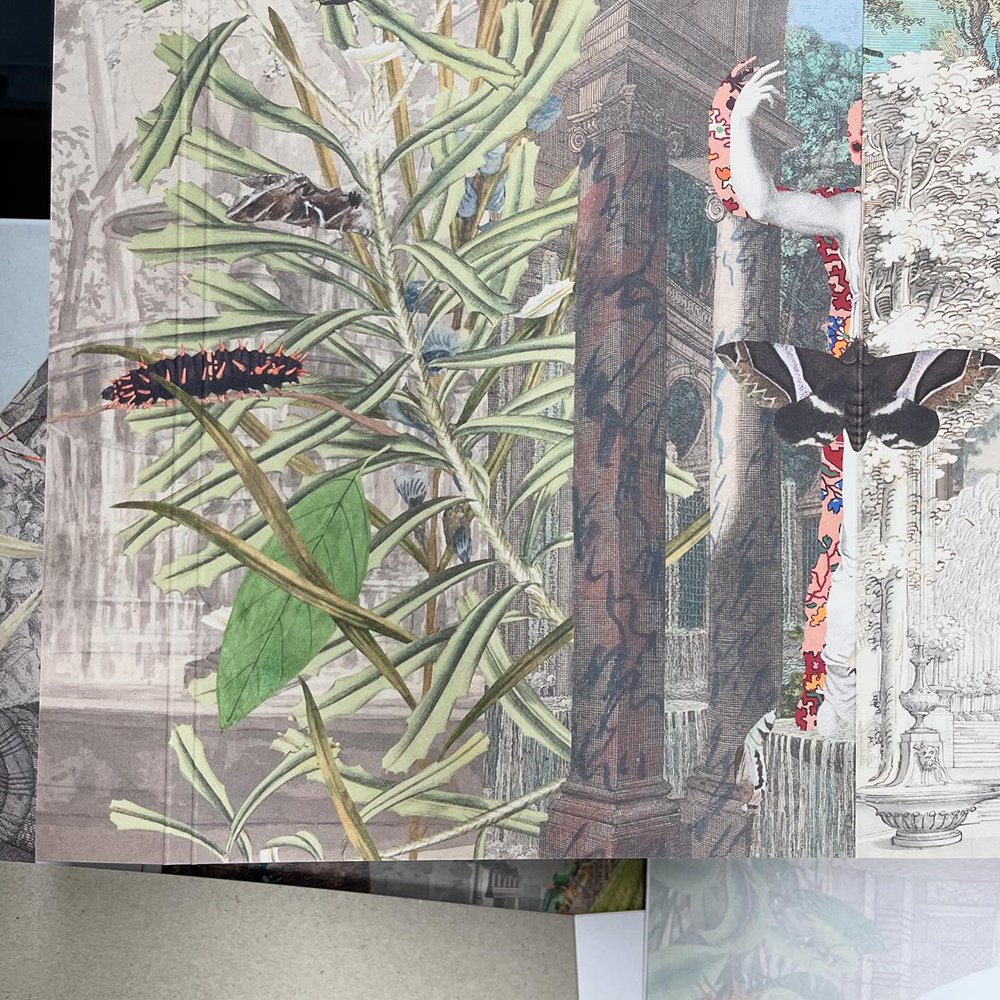

A Chelepteryx Collesi, and pairs of Aglaosoma lauta and Cerura Australis, et al. from:

Australian Lepidoptera and their transformations, drawn from the life by Harriet and Helena Scott

Harriet and Helena Scott (Harriet Scott, 1830–1907; Helena Forde, 1832–1910)

1864, London : John Van Voorst, Paternoster Row

Prints — book measures closed 43.6 x 35 x 1.3 cm — 1 printed book with 30 pages of text and 9 hand-coloured lithographic plates, quarter bound with marbled boards

Gloriously Wild: How artists Gracia Haby and Louise Jennison opened a tiny wildlife shelter in their backyard

Brita Frost

20th of September, 2024

The Lost Island

Gracia Haby & Louise Jennison are Melbourne-based artists. They collaborate to create exquisite artists’ books, zines, installations, collages and prints that address biodiversity loss and conservation. In 2023, their installation The remaking of things was a part of the Melbourne Now exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria. That year they also established Tiny but Wild, a wildlife shelter at their home in North Fitzroy in inner city Melbourne. The shelter allows them to care for injured Grey-headed flying foxes, Ringtail possums, Bush rats and Dusky antechinus until they are fully rehabilitated and can be slowly released back into the wild.

Sometimes nature changes us a little bit — we go for a walk and we feel better, we decide to stop using plastic straws — and sometimes, if we let it, nature can turn our entire life upside down and give it a good shake. Gracia and Louise have allowed nature to restructure their lives and their home, and in turn the animals they care for have taught them about wild lives, the perilous existence of the wild creatures in our cities and about taking action.

I was so inspired by this conversation, I hope you are too.

Brita: Can you tell me how you became wildlife carers and how it works?

Louise: We always wanted to be wildlife carers. We thought it looked amazing, but we didn’t think we could ever do it. And then COVID came along and we were walking a lot up at the Yarra Bend Colony with the flying foxes. That year, I adopted a bat for Gracia’s birthday and I was speaking to the person in Queensland doing the donation and she said, ‘Why don't you become foster carers for bats?’ She gave me the number for Bev from Bat Rescue Bayside and we called Bev up and we all immediately got along brilliantly. And then Bev said, if you get vaccinated, you can come and meet the pups.

We went over to Bev's place and she had two pups. She wanted to see how we picked them up and what our instinct was. We both picked one up. These little pups look up at you with their giant eyes and they look straight through your soul. It's immediate. The connection is so incredible. They're so intelligent. We were there for hours with Bev and we thought, over that summer, that we could go over and help out once a week.

Within a couple days though Bev and Paul called us and asked us if we would like to be foster carers? You need to be invited by somebody with a DEECA shelter license to become a foster carer. And if you want to apply for a shelter license, you need to have at least 12 months foster care experience and training.

Brita: And then you started the wildlife shelter?

Gracia: Around Christmas of last year, we officially launched Tiny but Wild, our little shelter in North Fitzroy. We could have stayed as Bev's foster carers, as we are a great little team, but she kept encouraging us. She wanted us to take the next step. And we’re so glad we did.

Louise: We work alongside Bev and Paul from Bat Rescue Bayside. They have the big flight aviary. When the bats are a bit bigger and need to start having flight time, they can go to Bev's place. And we can look after their animals when they go away, which is a big thing when you're looking after wildlife because you can't always be that mobile. In the summer, when things are busy, we're limited to two hours between feeds, so we never get far.

Brita: How many animals do you care for and for how long?

Gracia: Right now, we currently have Celeste, Lute, Linus, and Sylvie, four Ringtails possums ready for soft-release later this month. Iris, Monty, Betty, Little Lamb, and Stella, five Grey-headed flying foxes, most of whom will be ready to be soft-released in October, with the others to follow suit. And Ginni, Basil, Constance, and Rose, four Ringtail joeys who'll be ready for soft-release in autumn of next year (pictured below, and Bacchus too).

Flying fox pup season is in spring through to the new year. We're looking after them for that intense period and then from early-to-mid January they go to Bat Rescue Bayside where they can be in a larger creché group, socialise together and practise flying.

Louise: It used to be like clockwork. By early March, they were all heading off to the soft-release enclosure. The soft-release enclosure is a huge programme run by many dedicated folk cleaning, feeding and supervising and giving the bats time to acclimatise before the hatch is opened. By late March, they were heading into the wild and by April, everything was starting to wind down and people would have the winter to recover. But with the climate emergency, things are changing for all species. Now, we're getting pups coming in very early October, sometimes even September, and then we are getting youngsters all the way into April. We’ve only just started to slow down in May. We looked after 53 bats last summer. It was massive. And the Ringtail possums used to have a spring group and a late summer group. Now, you're getting ringtails coming into care weeks and weeks earlier.

Gracia: This year different shelters had little joeys coming in in July. Animals that would normally be waiting for spring are like, ‘No! It's spring now’. Patterns are changing. If it's a windy, stormy night, then you can anticipate it will be a busy morning with many rescues. Some of the rescues include flying foxes that may have become trapped on a balcony, collided with something, or clipped a powerline. Our days are flexible, because you never really know what cases might come in. There's always going to be ones that you can’t plan for. You also need to decide how much you can commit to, because this is voluntary.

Brita: Do you form close relationships with the animals?

Louise: You get really close to them, especially a pup who you’ve raised from a week old until they're ready for creché. They come into care at different stages and for different reasons. Some will come into care at only a few days old. And some will come in at around the four- or five-week mark when they're bit too big for the mum to carry. That's when a lot come into care because they accidentally fall off. And then some come into care, we call them river bats, because their mum has not made it safely back to camp. They're coming into care at eight weeks or something like that and those ones are a bit wilder. They've already had eight weeks of wildness and they don't need you quite as much, but they're still bottle fed at that point. They've had that colony experience.

Some will be very tactile and affectionate. Some will, no matter how used to you they get, not want to be held. But they will still want to climb on the ropes and come up and snuggle you on their terms. They're all individuals. The same with the ringtails. They've all got different personalities. There'll be ones that will run up to you and be all chatty and others that are shy. Different personalities, completely individual needs.

Brita: How has being a wildlife carer changed you?

Louise: When you first get to meet them, you're a predator and they're terrified of you. And they will be defensive. But you have to build trust with them as quickly as possible. When they’re an adult you have to be able to open their wing and check all their membrane or change a wound dressing or medicate them with antibiotics. They need to trust you enough to let you do that. Because you can't make a bat do something that they don’t want to do. If they don't want to take the meds, they won’t. You've got to work with a that. With any wildlife, you’ve got to work with them.

Gracia: And you're reading their body language or the situation as well. You get really close to them because you’re observing how they're responding. We always say, never rush a possum.

Louise: It's taught us a lot. It's certainly taught me to be a lot more present. We're both naturally very sensitive people and that helps with wildlife care because you are tapping into their personalities and sensitivities.

And it integrates you into a community of people who care about wildlife. When we release the possums each year, we work with Koala Clancy. It's a group up near the You Yangs (a mountain range west of Melbourne) where we have a soft-release programme for the possums on private property. When the possums graduate to being weaned, that’s when we start to pull back because they don't need us.

Gracia: That’s the reward. The animals that make it to the soft-release enclosure are the lucky ones. The ones who made it. It's the thing you're aiming and hope for, for all of them. We were talking to Janine who runs Koala Clancy and she had a really nice way of phrasing it: they have such proud, wild lives. The release is a beautiful return.

Louise: There are so many big, human-made dangers, but as Janine was saying, their wild life is so extraordinary. When you care for them, everything about their soul is wild. They're smart enough to know, ‘Okay. I'm in this house at the moment. I'm with these people. This is good. We can make this work.’ But as soon as they're back with their kind, they become so gloriously wild. An adult bat will be a softy, so affectionate, you put little grapes in their mouth and they love the pampering (during the recovery period). But the second they're back with the colony, you don't exist.

Brita: Can you talk about how it's changed your relationship with nature?

Gracia: It has on many levels. After this interview, we'll be going to get browse for the possums because we don't have anything for them for tonight. In that sense, when we're driving or walking, you’re always looking. It's changed our knowledge of trees. We know that possums don’t like the bluey grey eucalypt, but they do like the yellowy green ones. So you are wandering around and there’s a whole other world that has opened up. And that smell of eucalypt when they're eating the leaves, it’s really fresh. It's obviously eucalyptus, but it's a peppery smell. Or a lemon myrtle minty smell. They’re small little everyday things, but it’s indicative of how you feel about all the other big things as well. It's more detail, isn't it? Adding more detail into your world.

Brita: How are humans impacting the lives of wild animals and what we can do about it?

Louise: There are so many solutions. It's figuring out what you can do, what your skills are and then making nature a part of your life. Because it already is. It’s just realising that I guess. You can change your super (retirement fund) and your banking so that it's ethical. That's a massive change. You can get solar and do as many things as you can to tread lightly on the planet. Join local planting groups and weeding days, also cleanup days. They’re hugely important because they have an immediate impact on ecosystems and they'll also have an immediate impact on your joy in life.

The hard bit is not doing anything. If you don't participate in the solutions, it’s just all too sad. You have this feeling that you don't make a difference. And we all do, we all make a difference. Some of the biggest changes have been groups of normal people banging at that wall until it tips over. There will be a tipping point when these solutions start to become mainstream. I mean, what's the worst that could happen? We could have healthy soil, we could have fresh air, we could have fresh water. We could have joy in life. We could be reciprocal with nature and be enriched as individuals and as a society.

Read online (The Lost Island)

Read online (Marginalia)