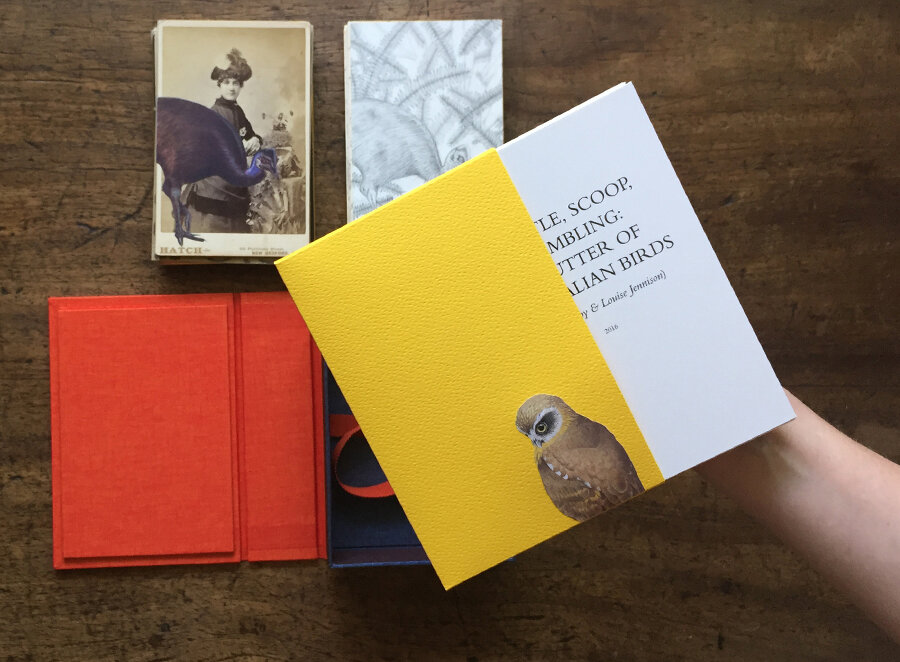

PRATTLE, SCOOP, TREMBLING: A FLUTTER OF AUSTRALIAN BIRDS

From Adelie penguin (Pygoscelis adeliae) to Zebra finch (Taeniopygia guttata) — well, not quite.

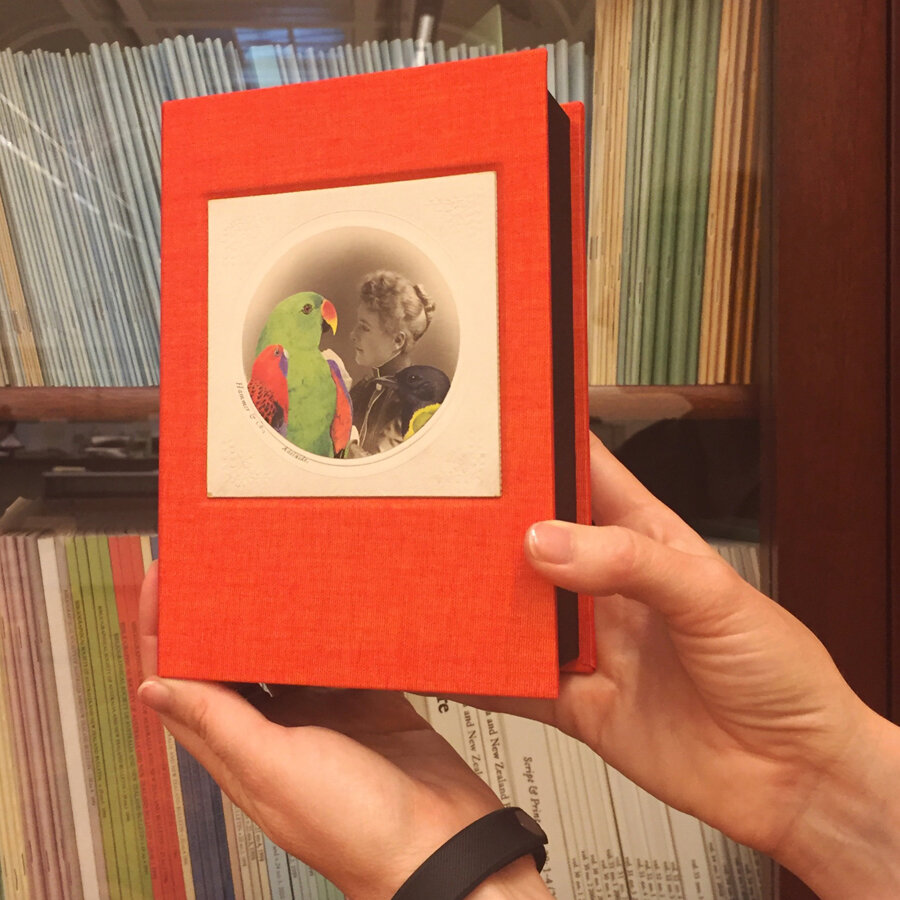

Gracia Haby & Louise Jennison

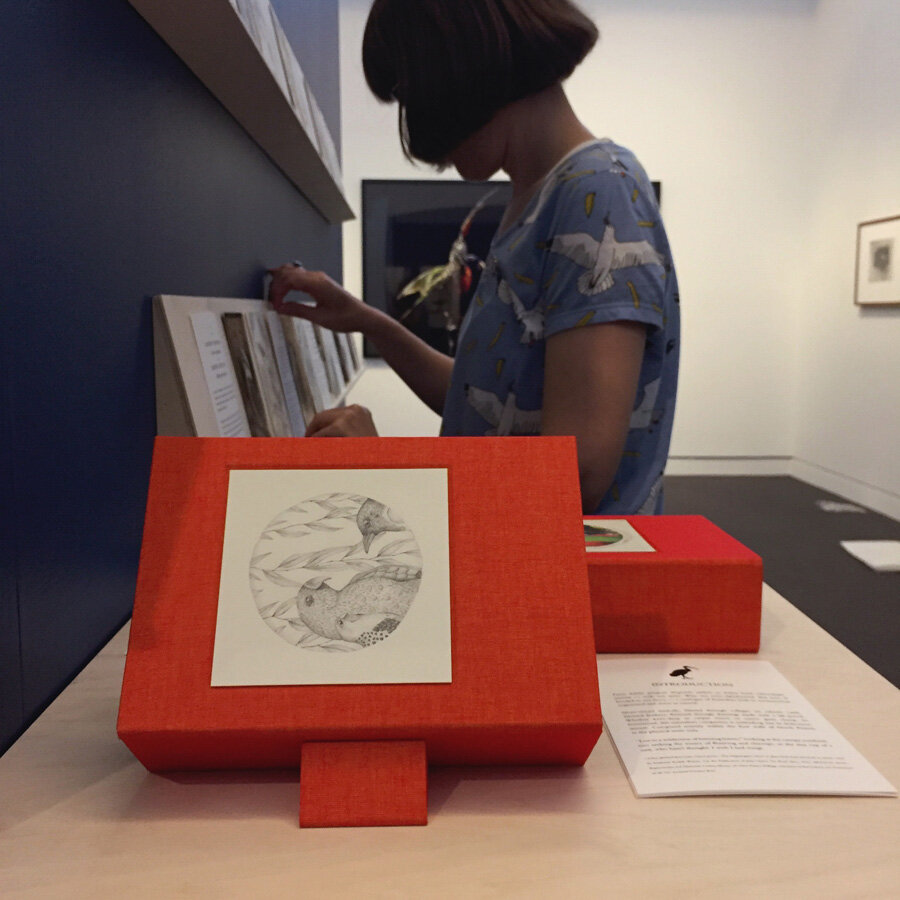

Prattle, scoop, trembling: a flutter of Australian birds

2016

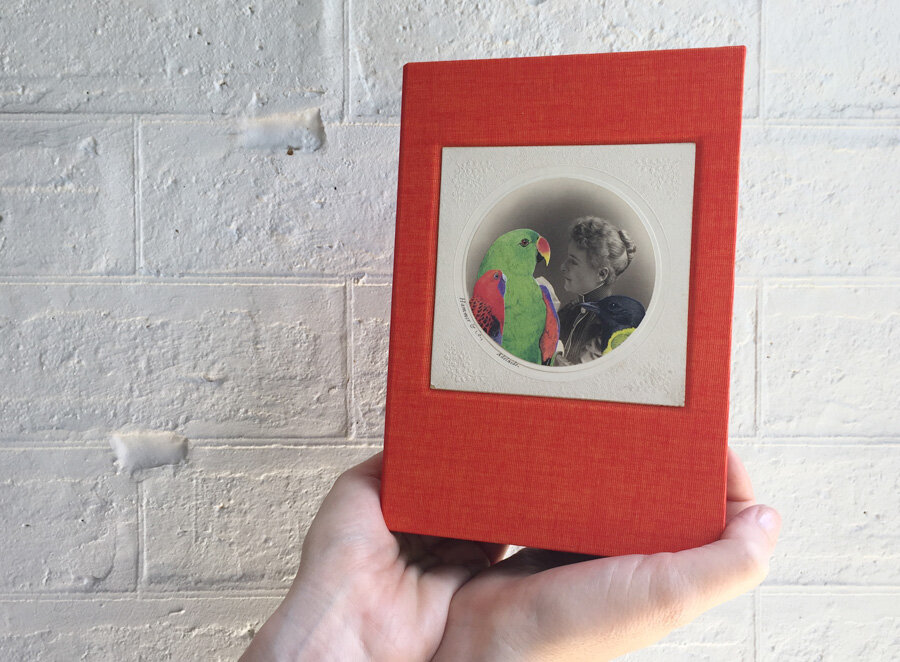

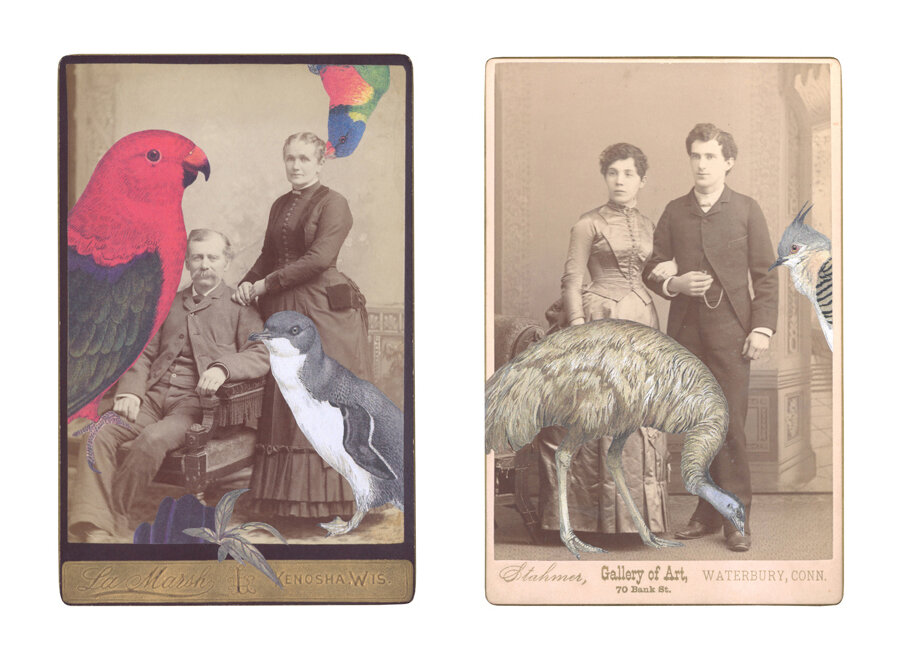

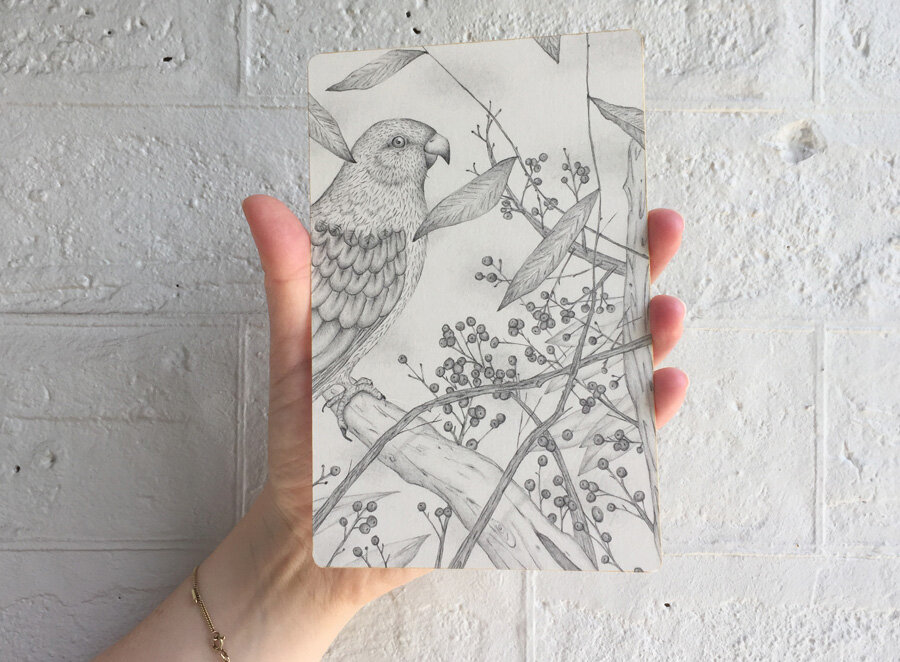

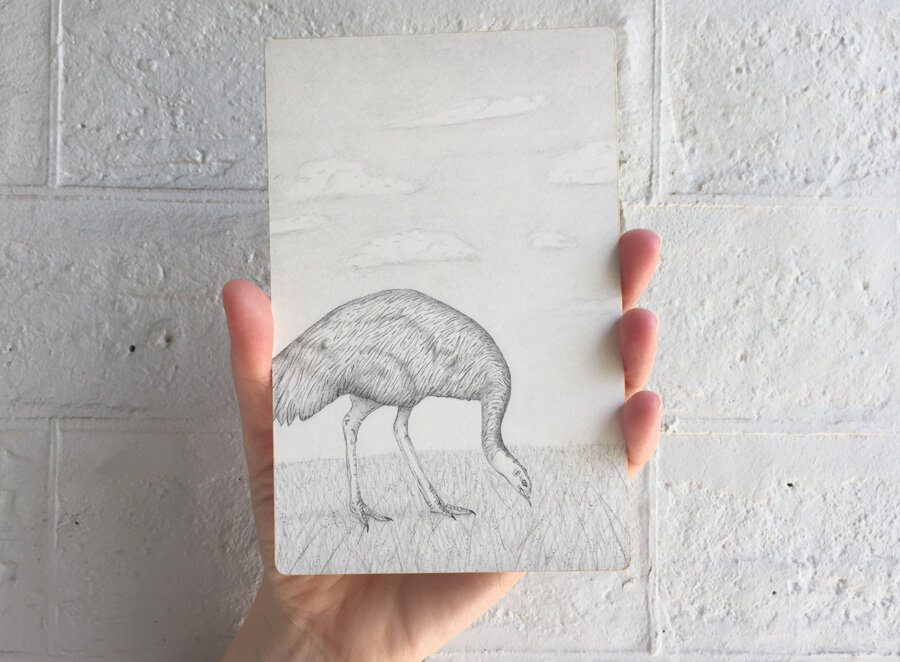

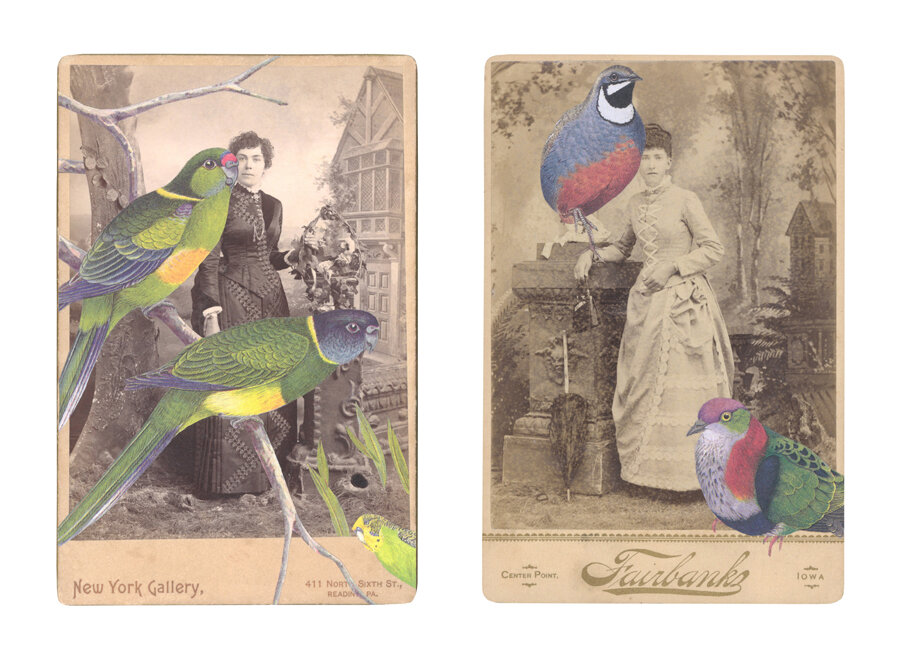

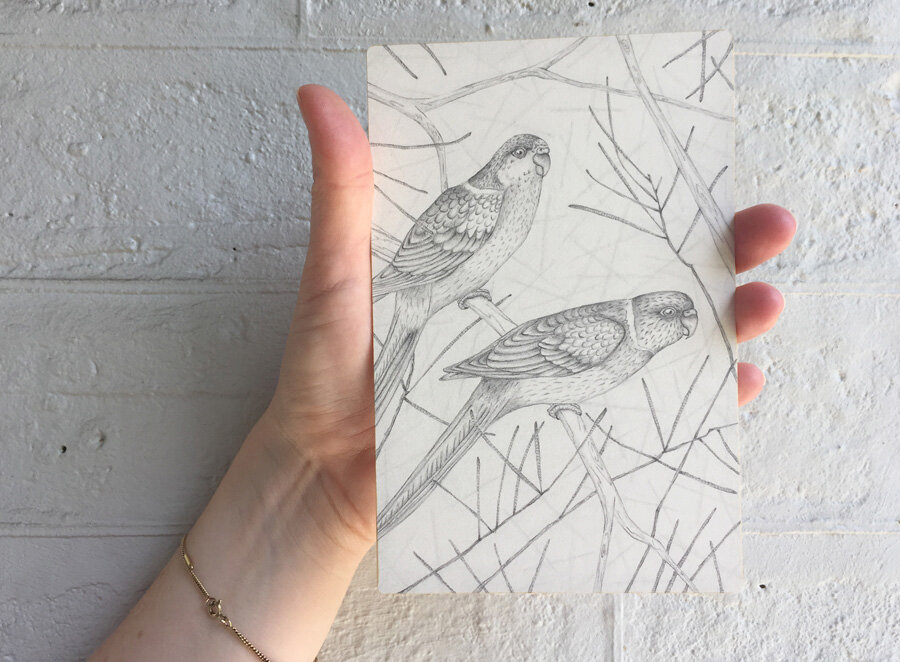

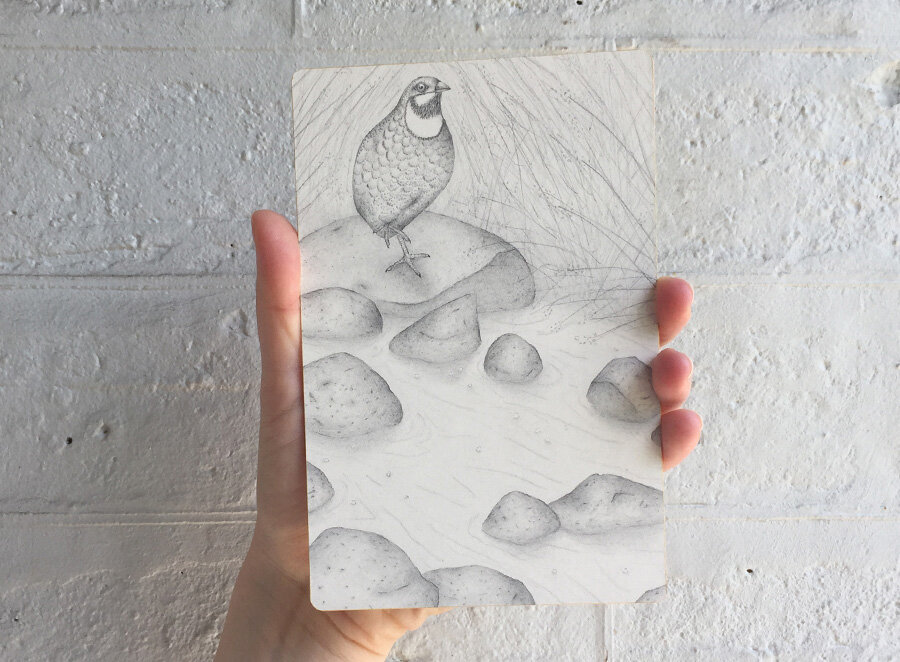

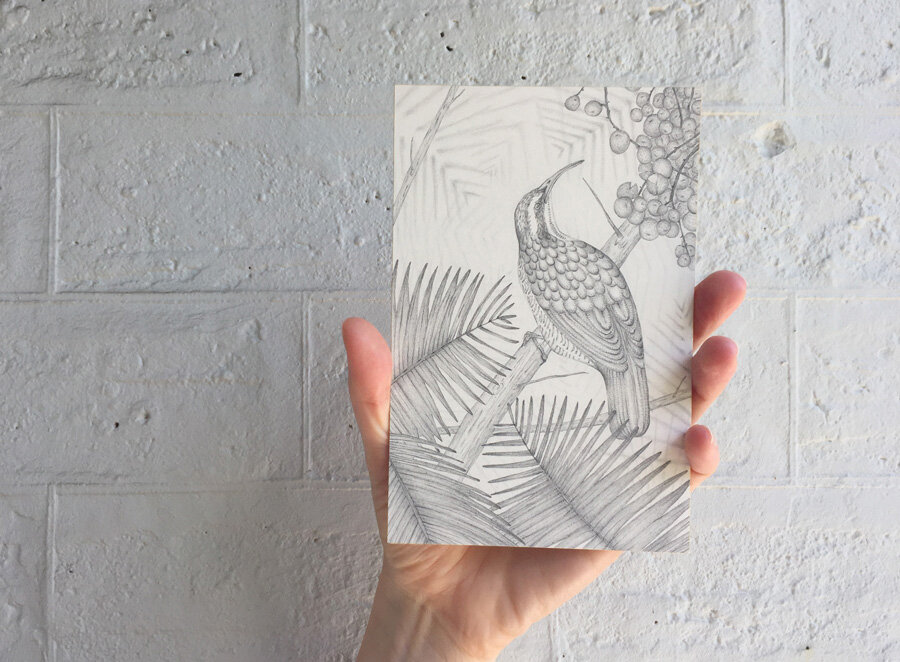

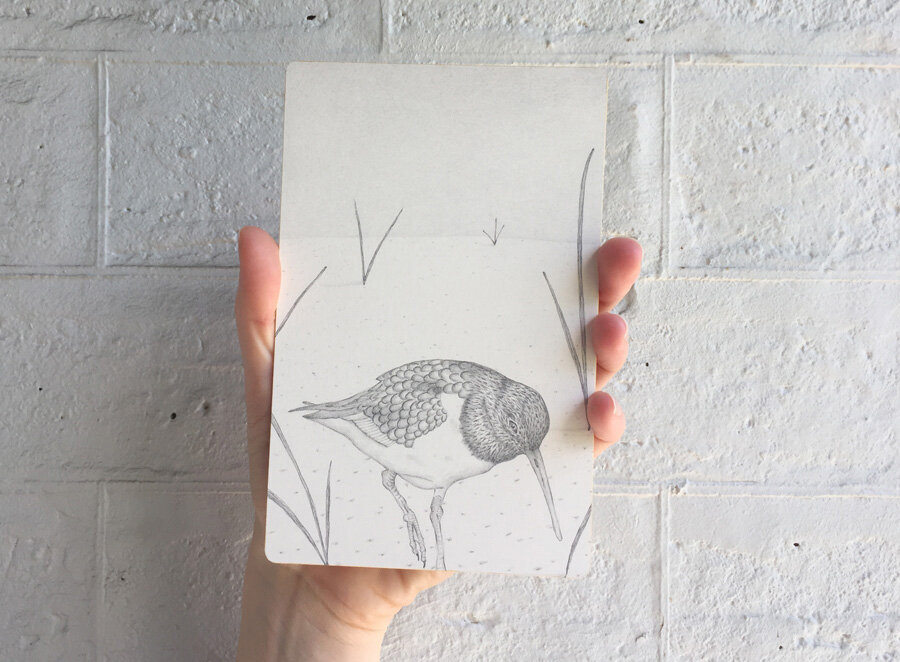

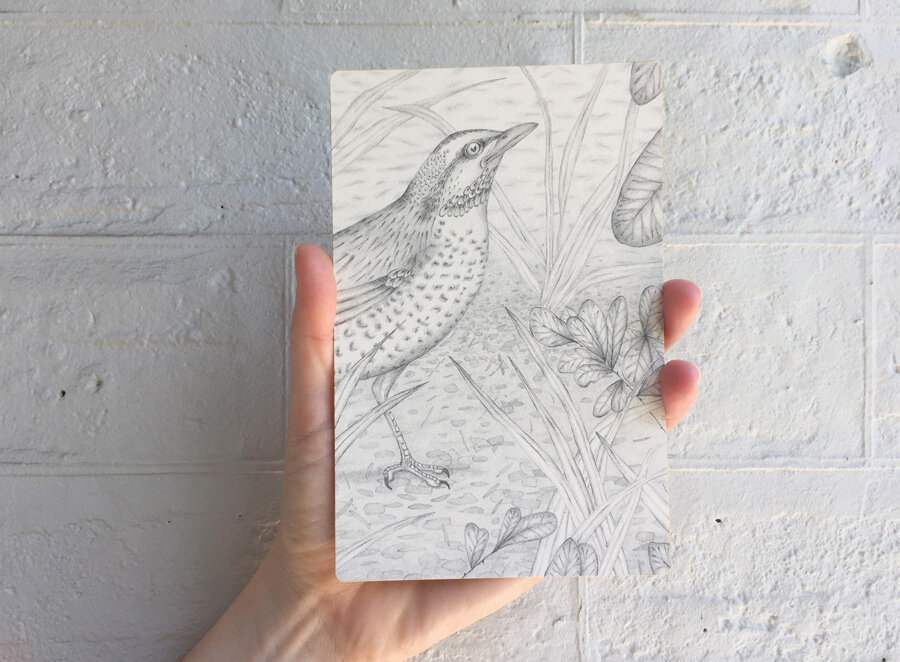

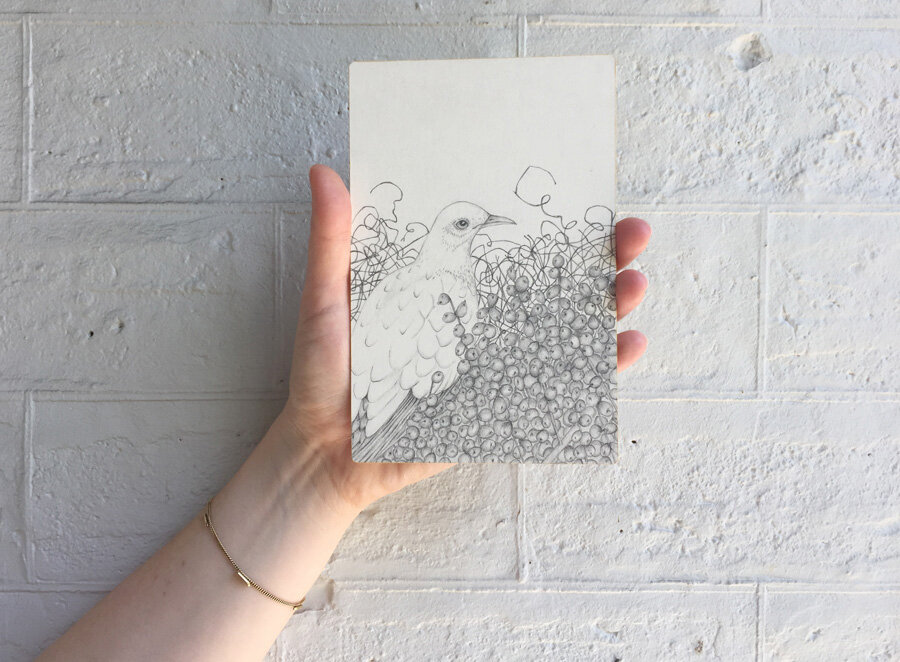

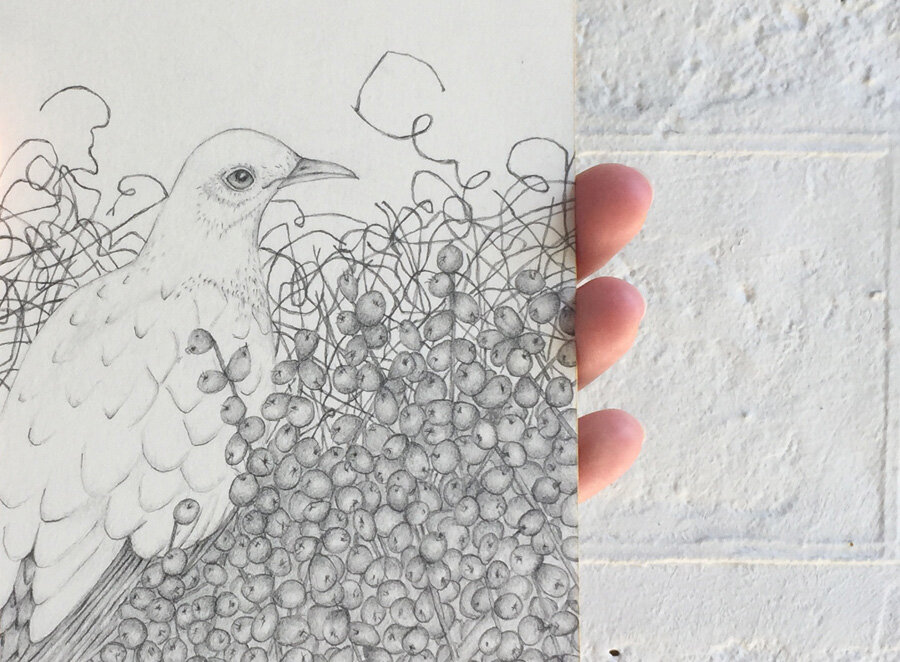

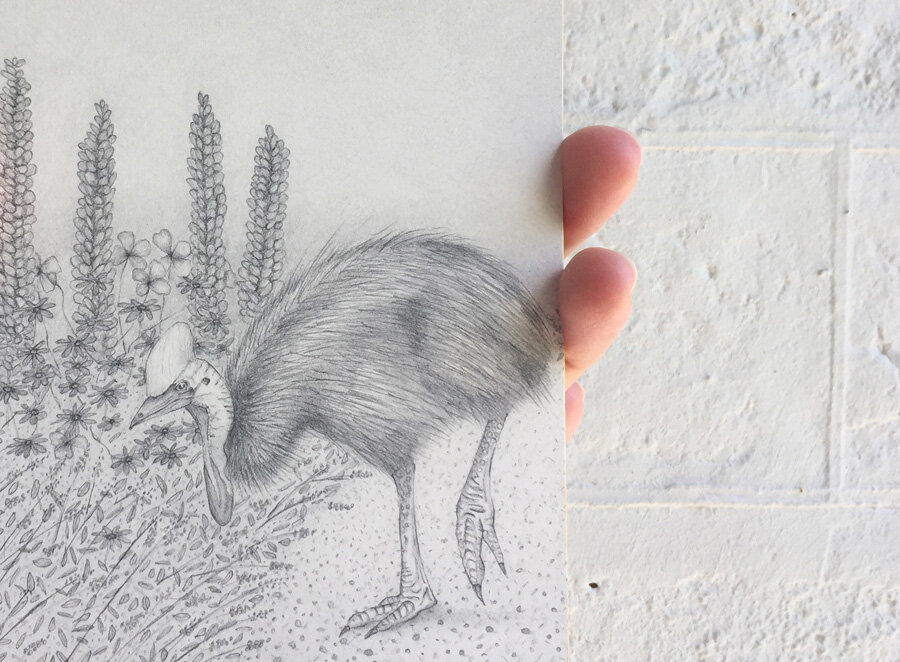

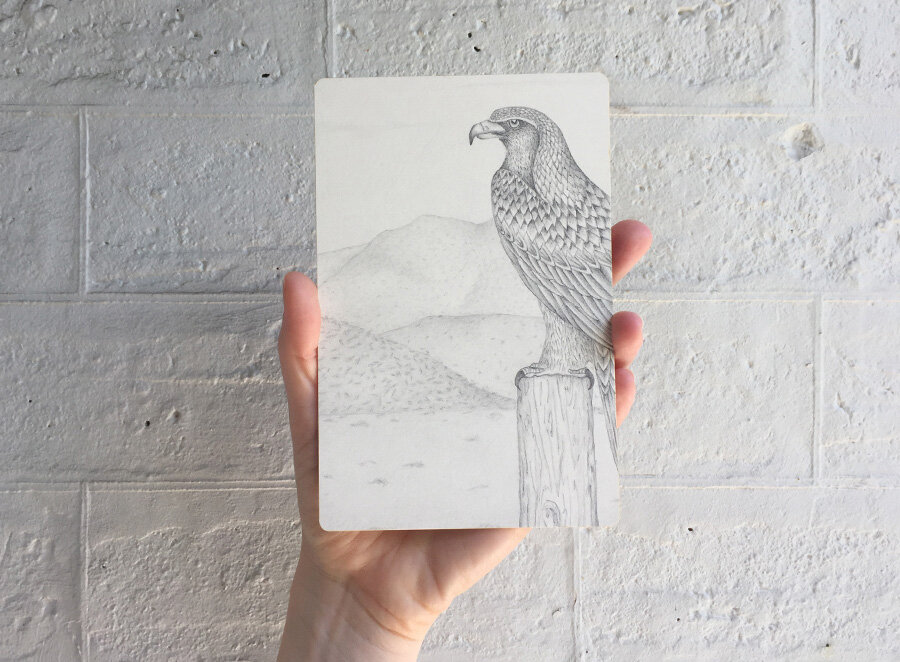

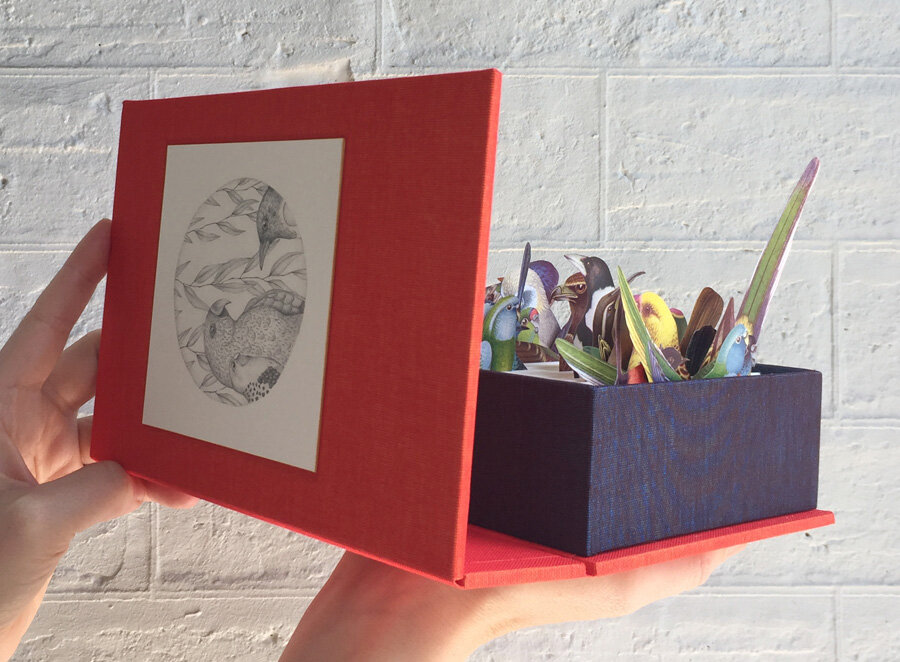

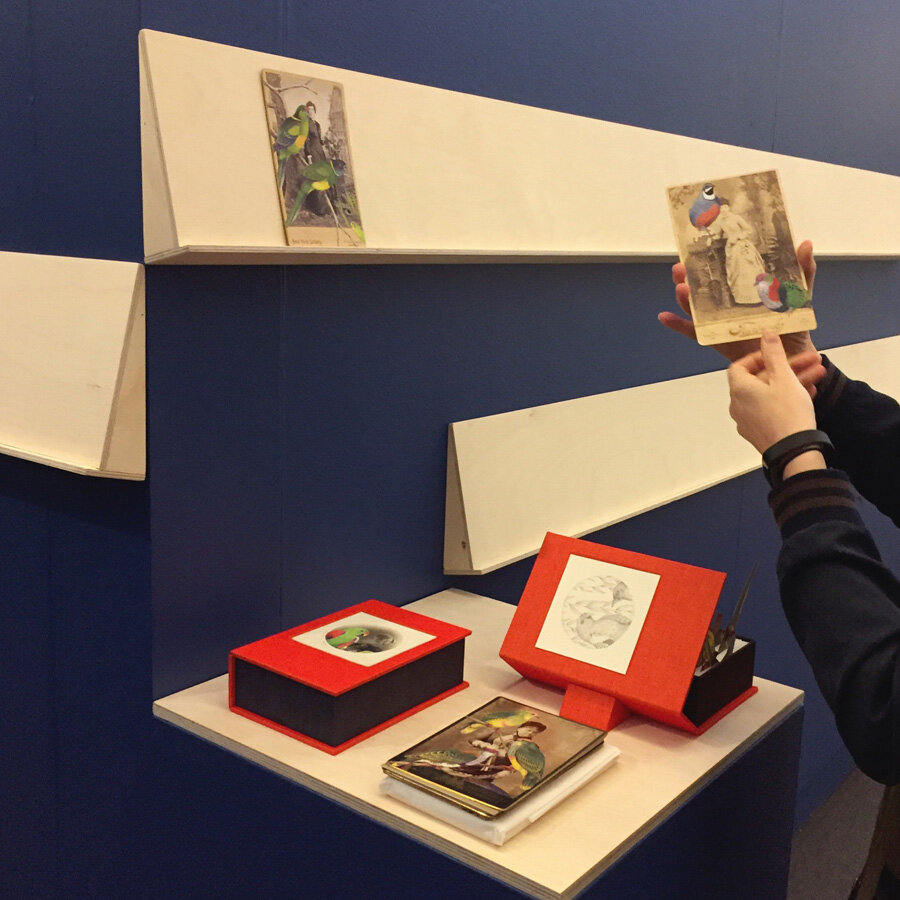

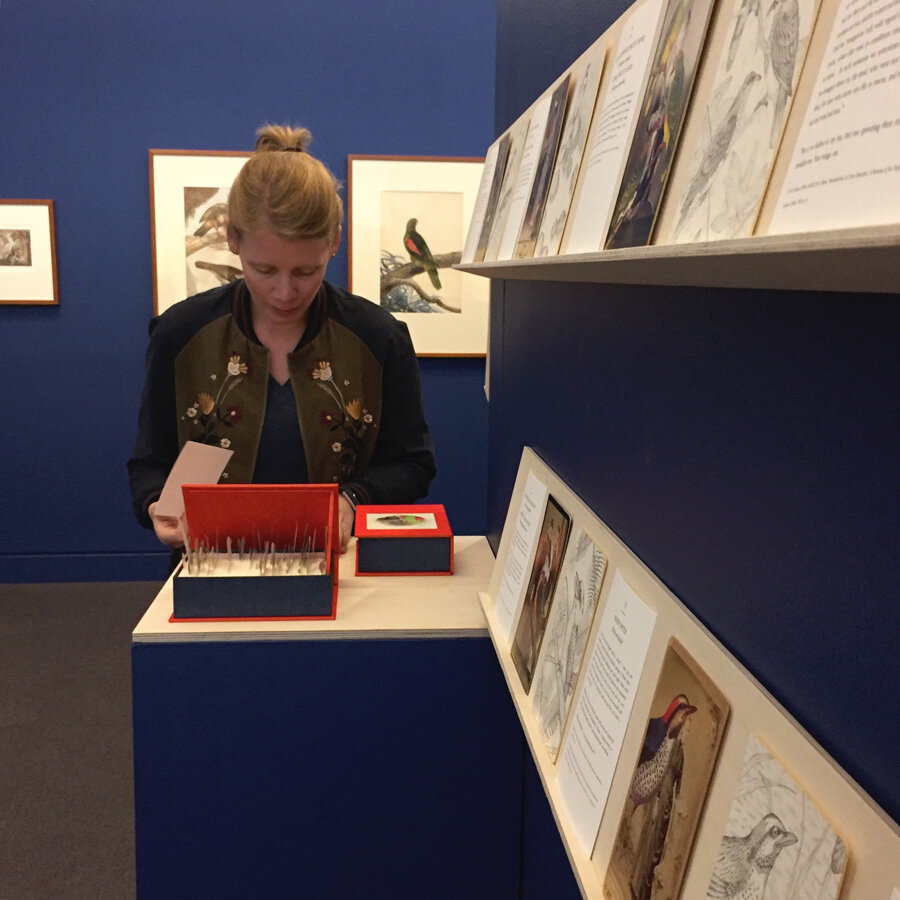

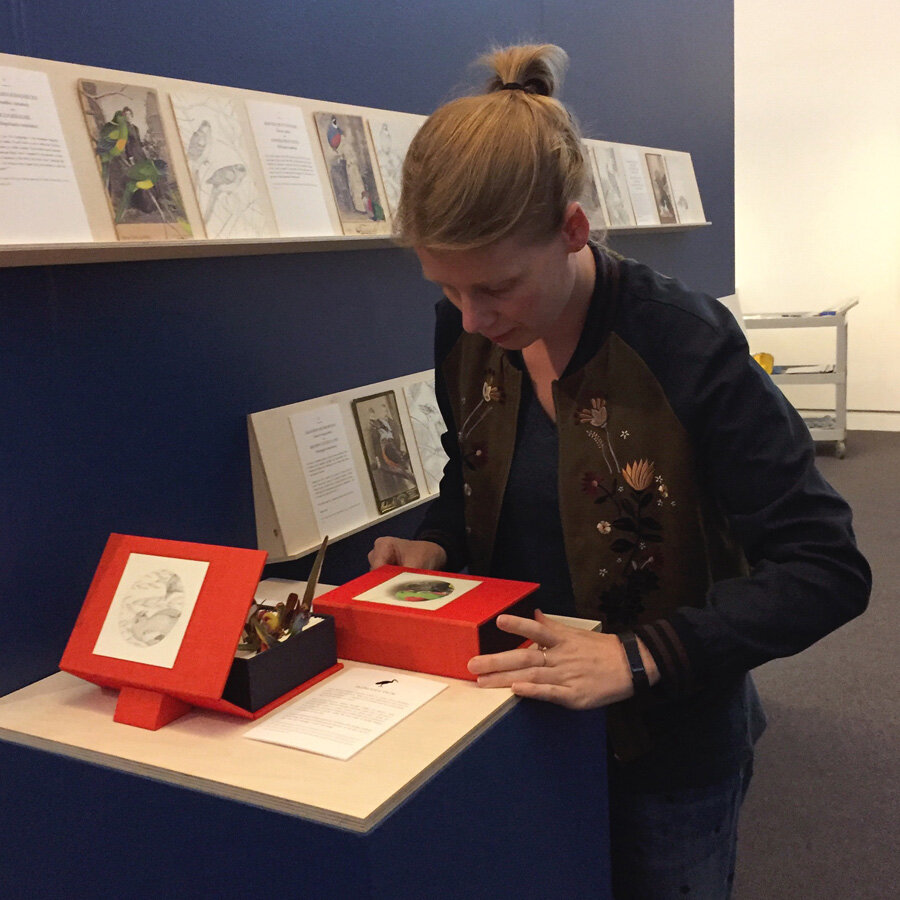

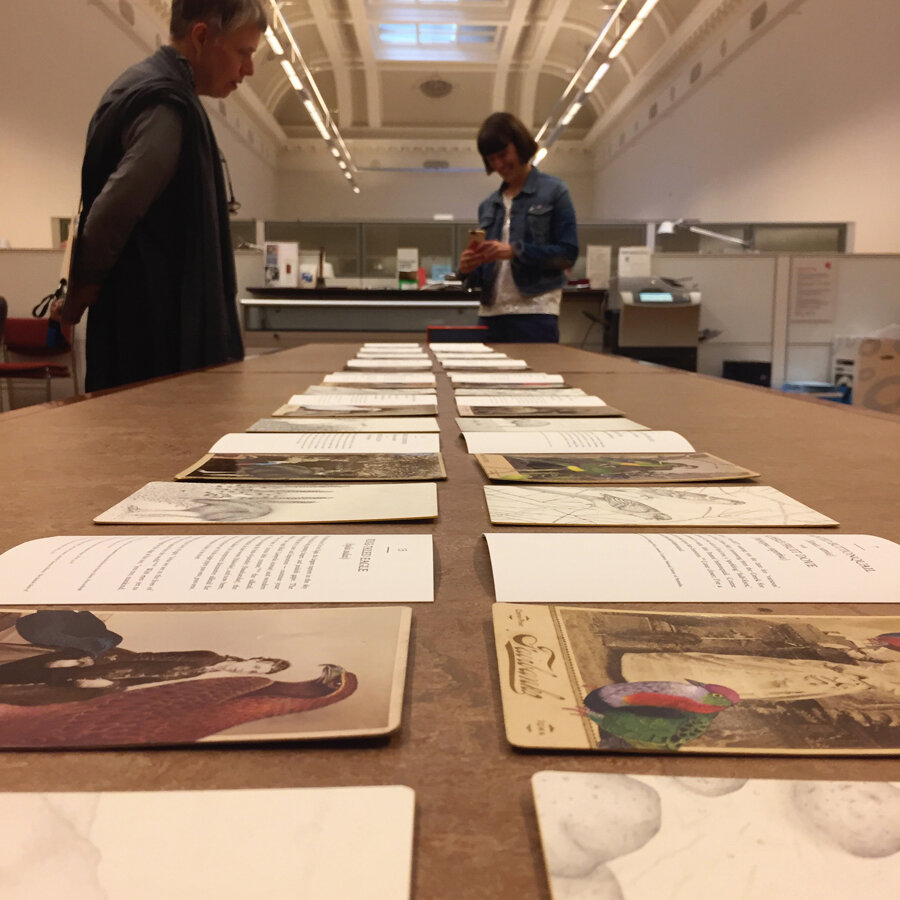

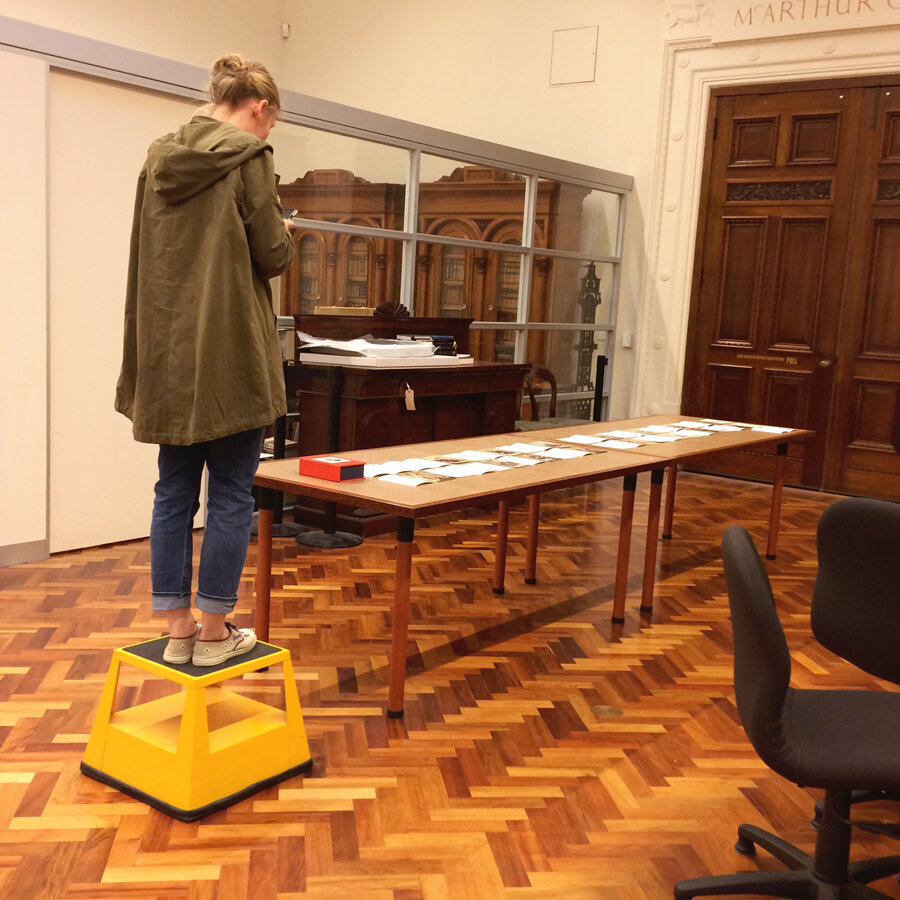

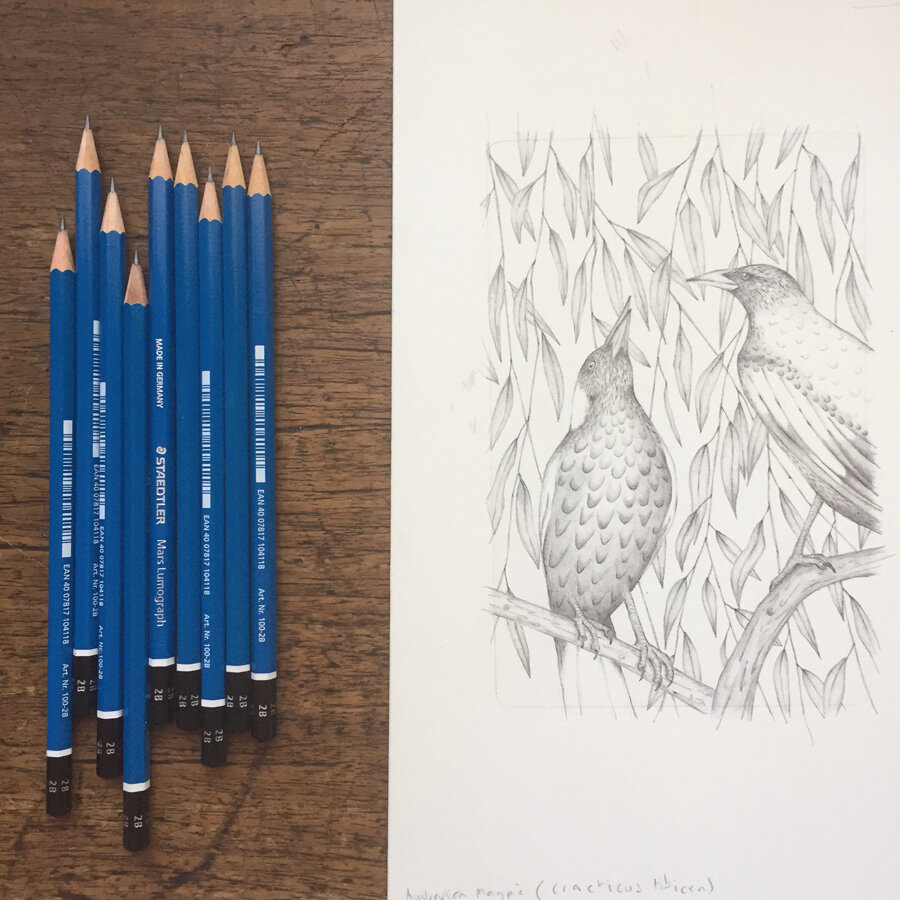

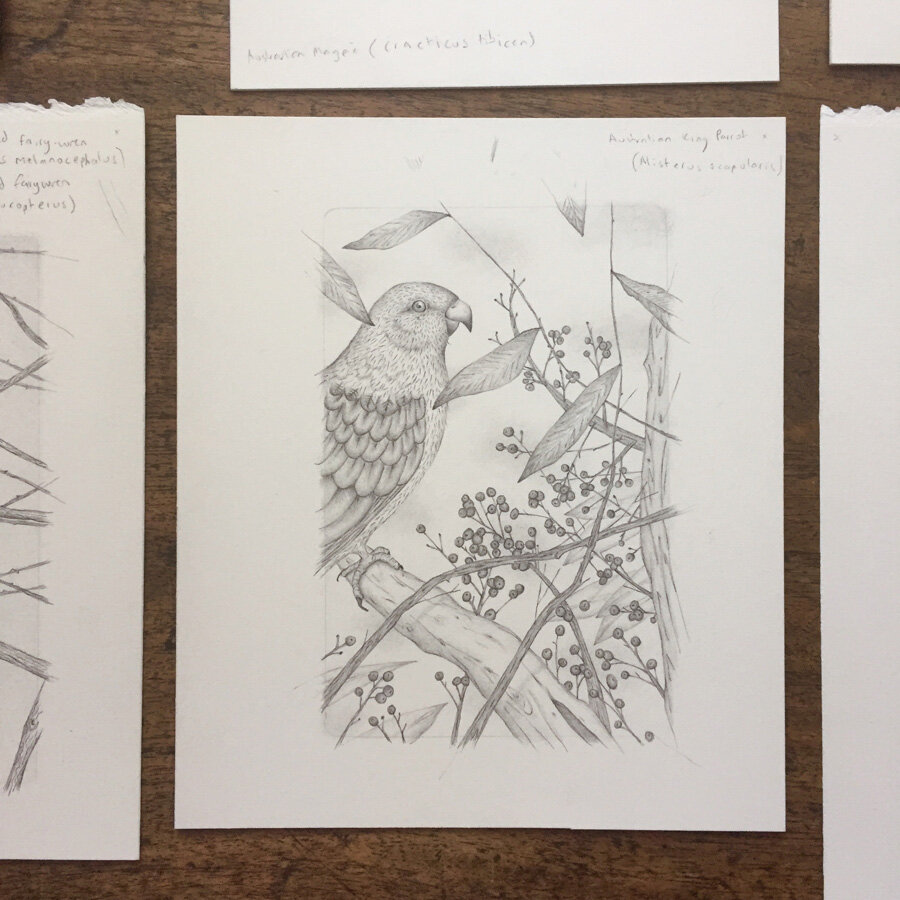

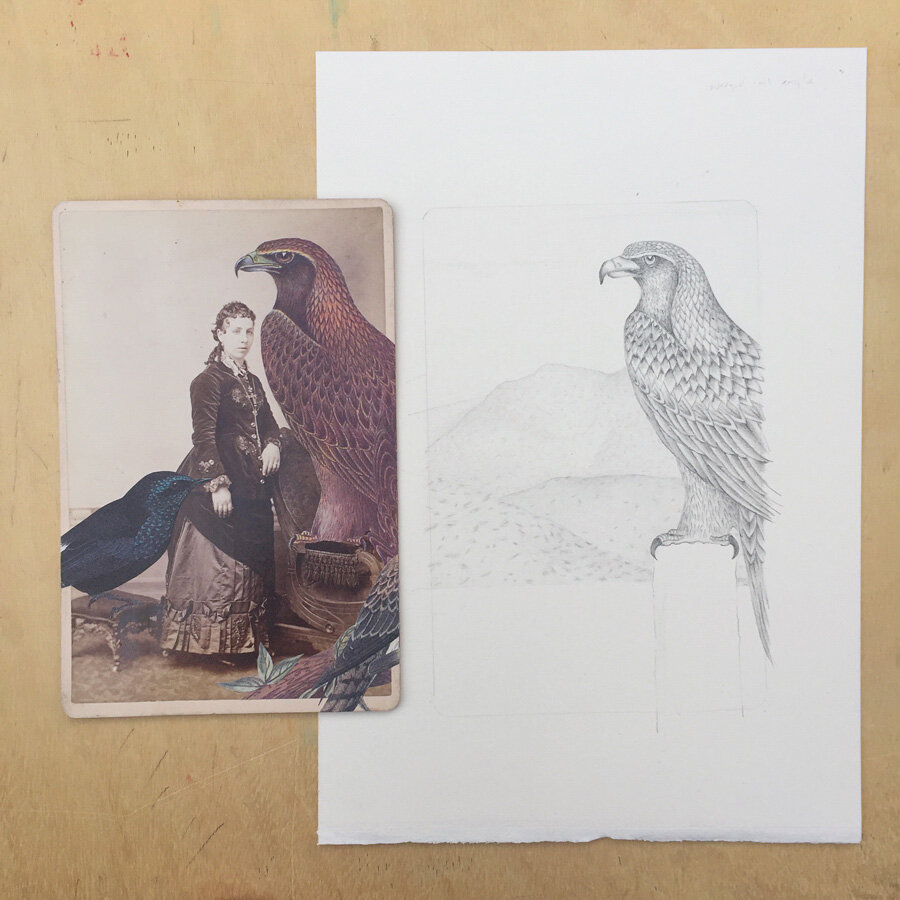

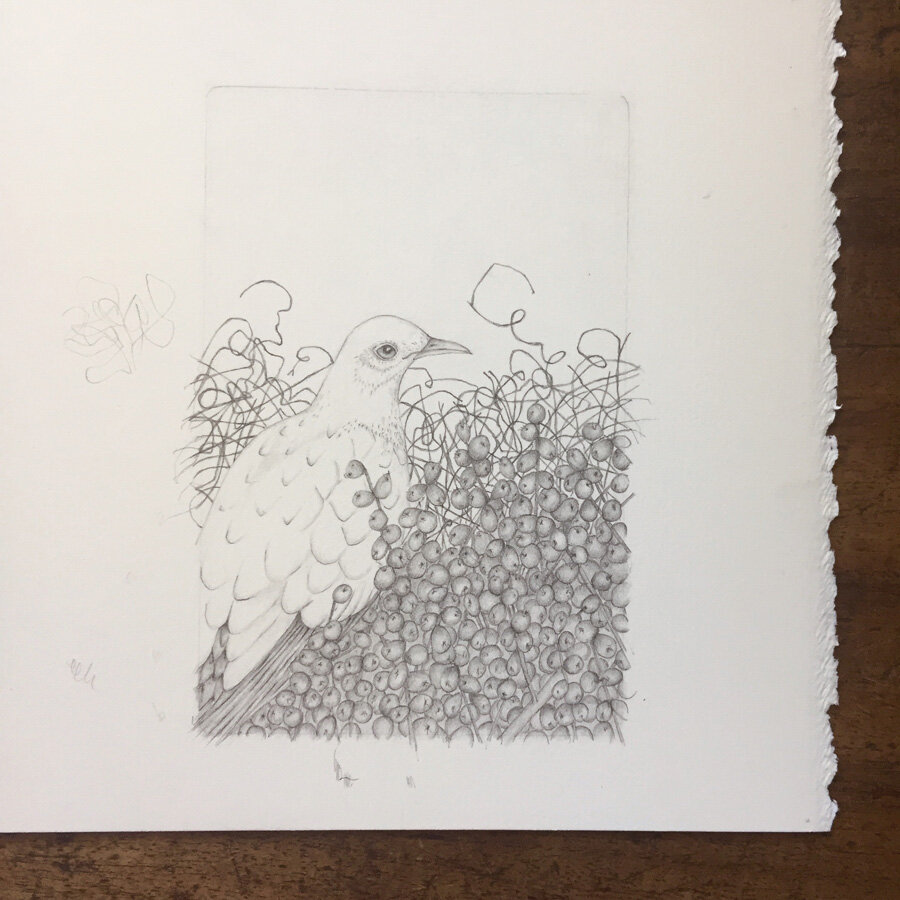

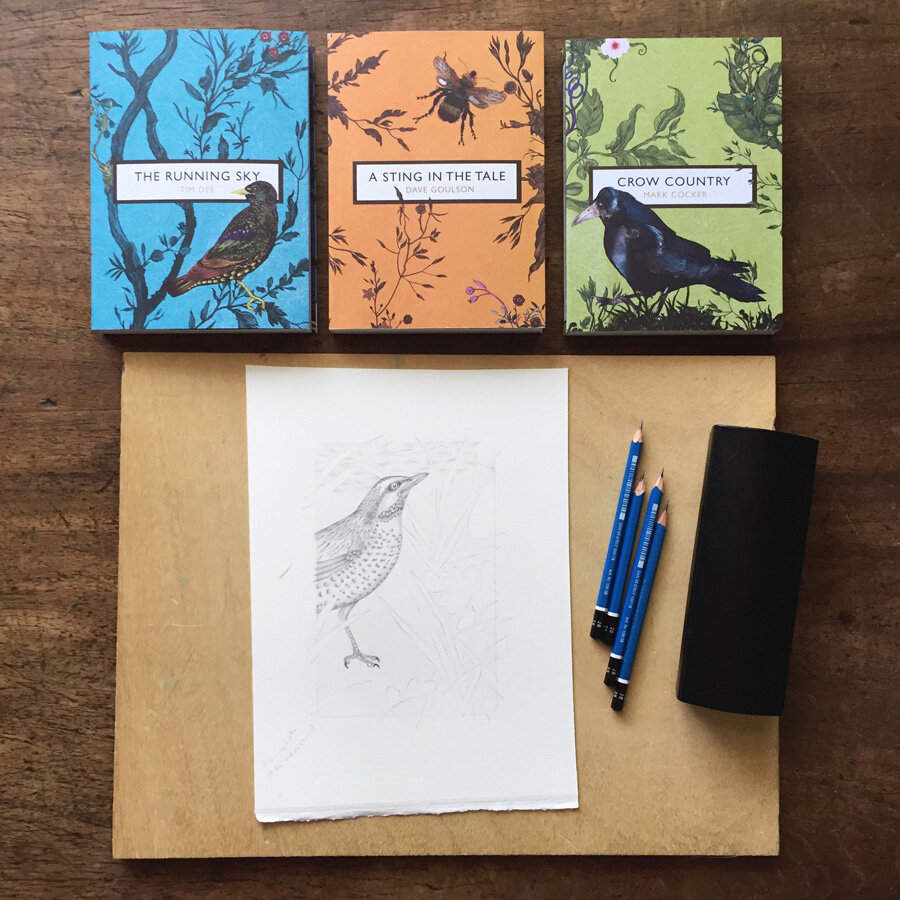

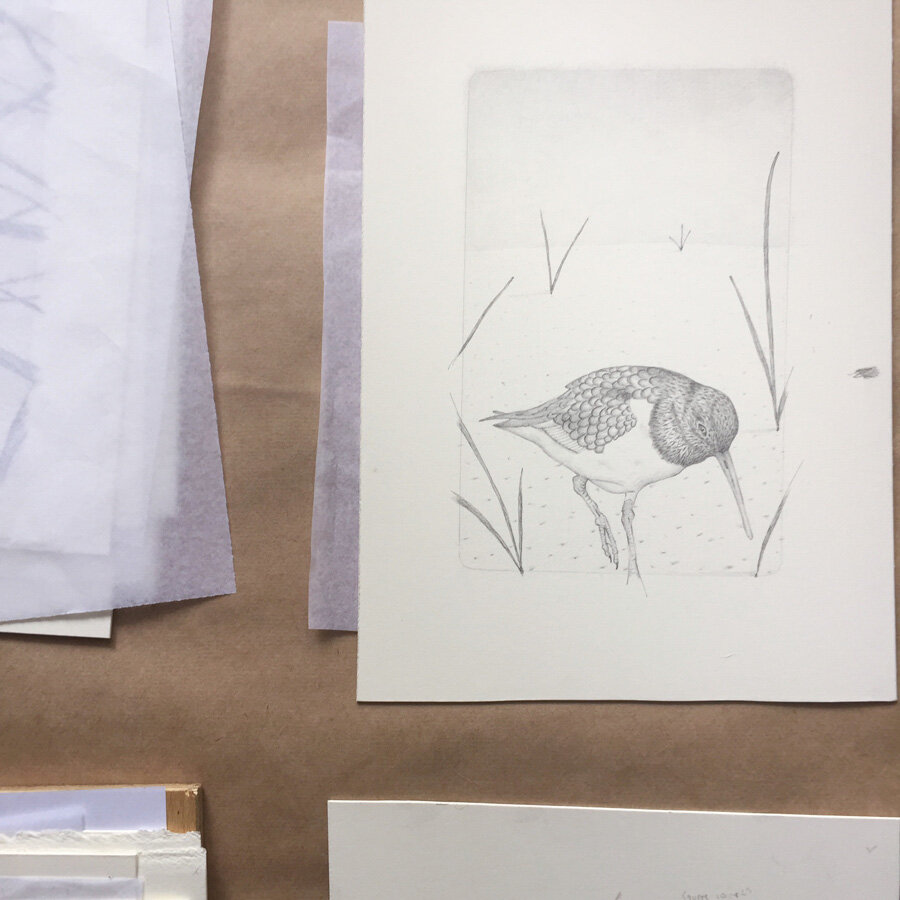

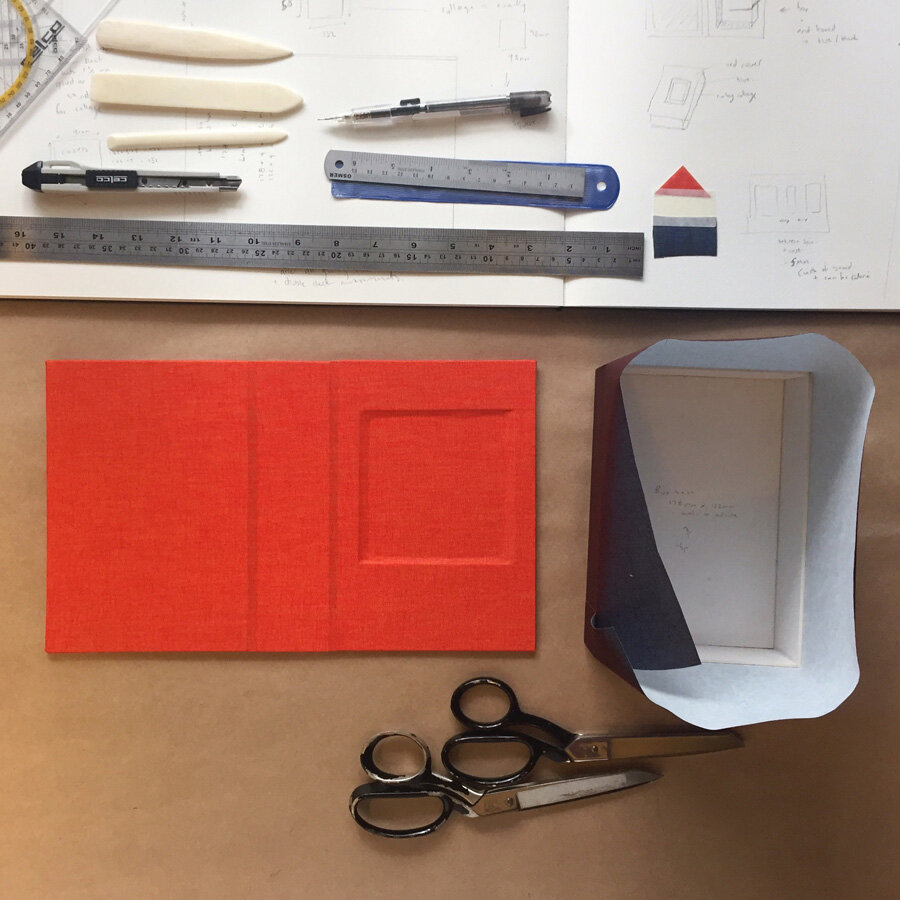

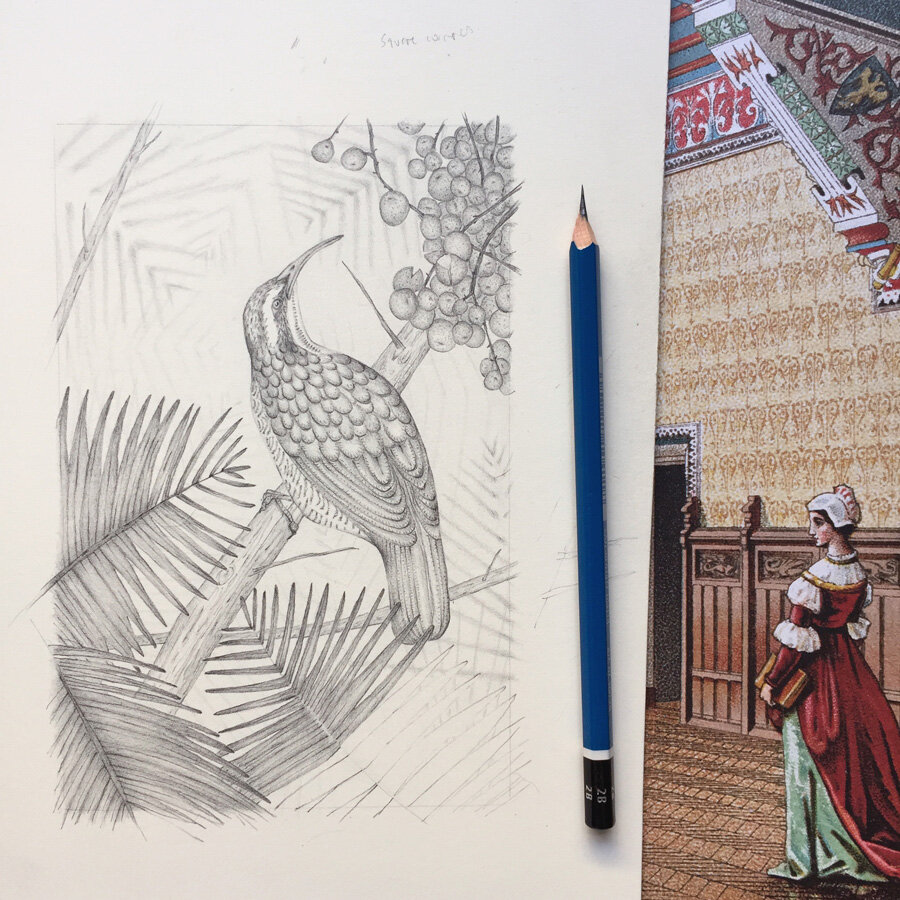

Artists’ book, unique state, featuring 15 individual collages on cabinet cards with pencil additions, and accompanying narrative (by Gracia Haby), 15 pencil drawings on Fabriano Artistico 640gsm traditional white hot-press paper with metallic paint trim

Housed in a cloth Solander box (by Louise Jennison), with inlaid collage

Exhibited alongside

An index box of Australian birds still fluttering

2016

Collage housed in a cloth Solander box, with inlaid drawing

From Adelie penguin (Pygoscelis adeliae) to Zebra finch (Taeniopygia guttata) — well, not quite. Why, not even alphabetised. But true, if bended to suit fancy — a catalogue of Australian birds in environments augmented and closer to natural. Silver-voiced bird calls, filtered through collages on cabinet cards. Silvered feathers, fluttered through drawings made with a 2B pencil. Whether knee-deep in carpet weave or native grass clump, this naturalist's companion is misleading, but its dedication, sincere.

“Lost in a wilderness of listening leaves,”[i] looking at the canopy overhead, eyes seeking the source of flittering and chirrups, or the tiny cup of a nest, who hasn’t thought: I wish I had wings.

Note:

[i] A line plucked from John Clare’s poem, ‘The Nightingale’s Nest,’ to place both bird and book in nature, quoted by Stephanie Kuduk Weiner, ‘On the Publication of John Clare’s The Rural Muse, 1835,’ BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History, ed. Dino Franco Felluga, extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net, accessed October 2016.

●

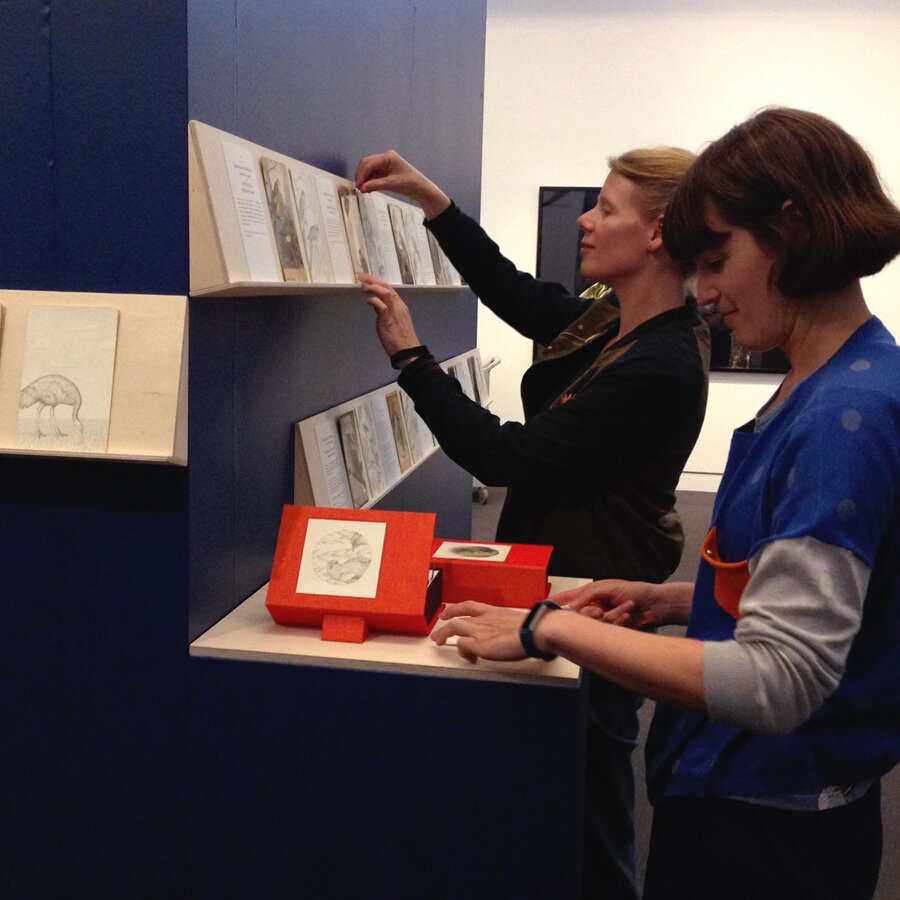

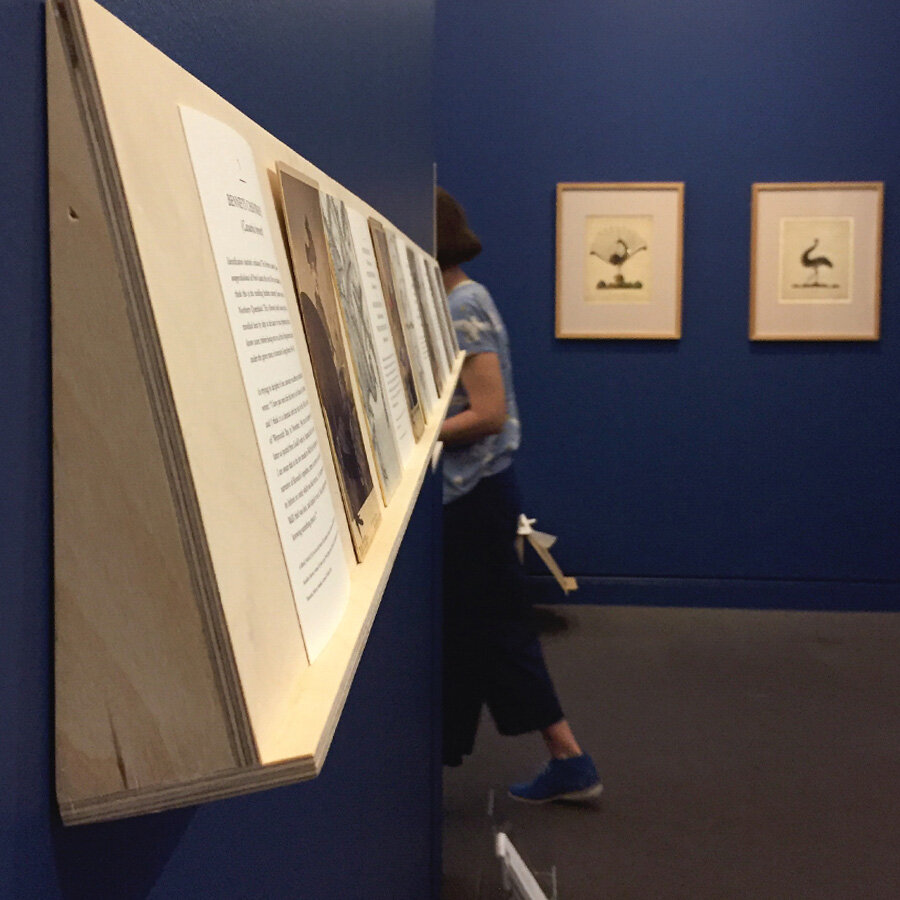

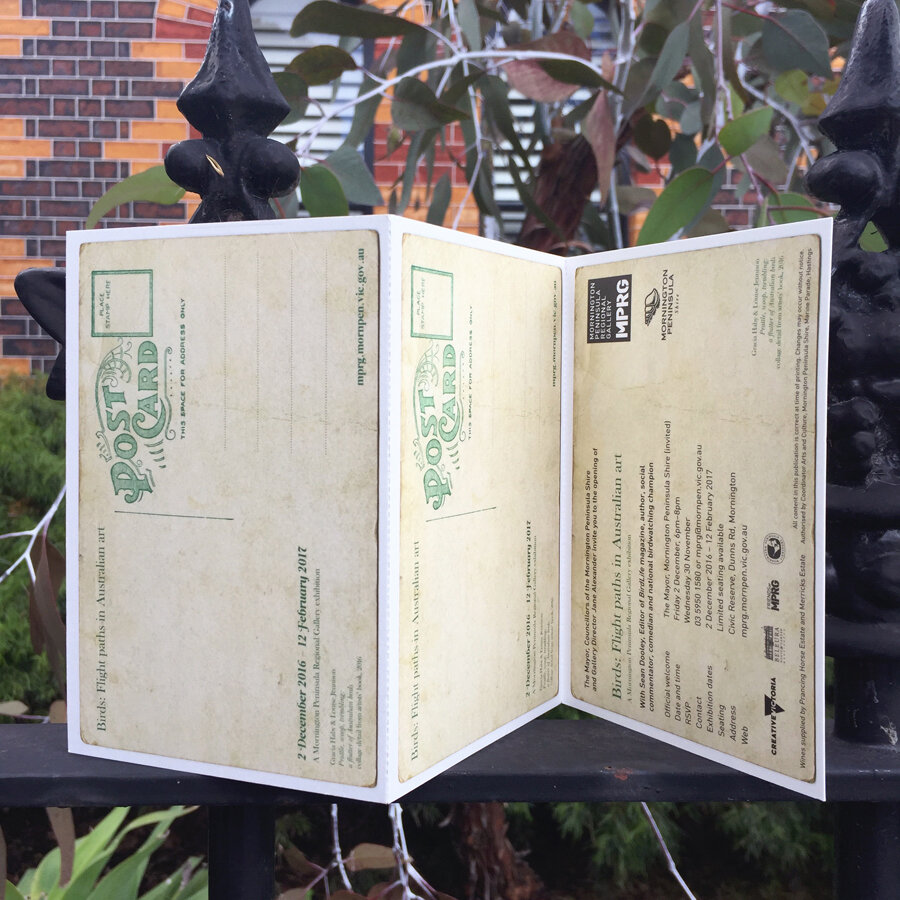

Birds: Flight paths in Australian art

Prattle, scoop, trembling: a flutter of Australian birds was created especially for and exhibited in its entirety as part of Birds: Flight paths in Australian Art at Mornington Peninsula Regional Gallery. Also included in the exhibition, alongside John Lewin’s Squatter pigeons and a decorated emu egg, was our print, Underneath Soane’s ‘star-fish’ ceiling, the library at No. 12 proved anything but quiet (2016), and around the corner, A Flight of Twelve Southern Hemisphere Birds (2013).

Birds: Flight paths in Australian art

Friday 2nd December, 2016 – Sunday 12th February, 2017

Mornington Peninsula Regional Gallery

Civic Reserve, 350 Dunns Road (corner of Mornington-Tyabb Road and Dunns Road), Mornington, Victoria

Brook Andrew; Arthur Boyd; Richard Browne; Penny Byrne; Kate Daw & Stewart Russell; Adrienne Doig; Marian Drew; Juan Ford; Gracia Haby & Louise Jennison; Fiona Hall; Treahna Hamm; Hans Heysen; Patrina Hicks; Judy Holding; Clara Ngala Inkamala; Judith Pungarta Inkamala; James Stu; Leila Jeffreys; Martin King; John William Lewin; Sydney Long; Joseph McGlennon; James Morrison; Munduwalawala; David Noonan; Jill Orr; Trent Parke; Kenny Pittock; Ben Quilty; Kate Rohde; Heather Shimmen; James Smeaton; Valerie Sparks; Henry Steiner; Tjunkaya Tapaya; Claudia Terstappen; Rover Thomas; Christian Thompson; Albert Tucker; Louise Weaver; Guan Wei; Fred Williams; John Wolesley; Salvatore Zofrea

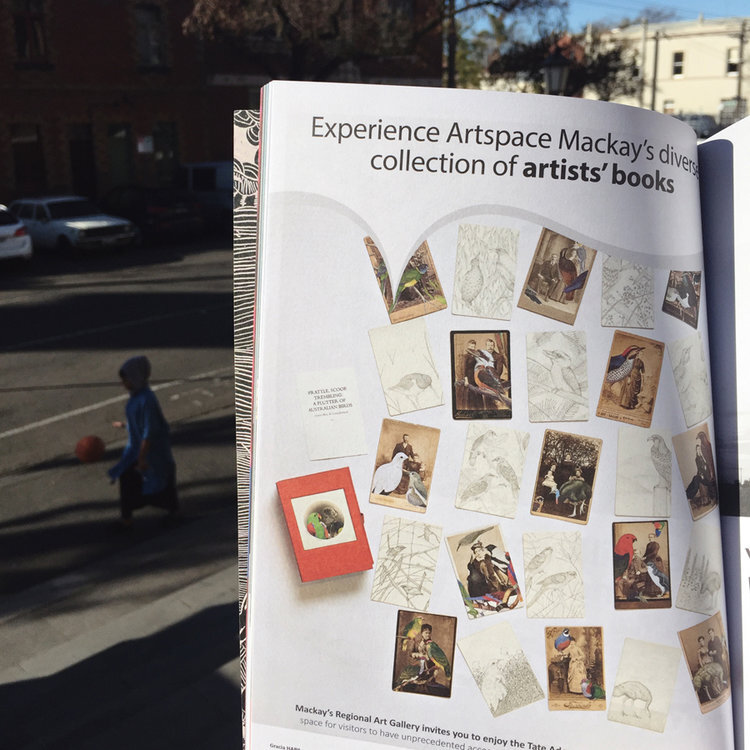

Prattle, scoop, trembling: a flutter of Australian birds, alongside Closer to Natural, has been acquired by Artspace Mackay.

As part of Artspace Mackay’s “diverse collection of artists' books,” which you can “enjoy in the Tate Adams Reading Pod, a purpose-built space for visitors to have unprecedented access to the collection” (Art Guide), turn the pages, get up close, and enjoy.

Artspace Mackay

Civic Centre Precinct, Gordon Street

Mackay, Queensland

Prattle, scoop, trembling: a flutter of Australian birds has since been exhibited as part of Focus on the Collection: Gracia Haby & Louise Jennison in the Foyer Gallery of Artspace Mackay (Friday 30th of November, 2018 – Sunday 3rd of February, 2019). The exhibition, drawn from the Mackay Regional Council collection, also included our artists’ books Find your place (2007); Small collection (2008); Postcards from... a key to make your own world visible (2009); A vagary of impediments & a sneak of weasels (2009); Tumble & fall (2009); This evening, however, I am thinking of things past (2009); Closer to Natural (2016); and Paw Pad Path (2018).

﹏

RELATED LINKS,

SEE PRATTLE, SCOOP, TREMBLING: A FLUTTER OF AUSTRALIAN BIRDS AS IT DEVELOPED, ON THE WORKING TABLE

THE INNER HEARTBREAK OF BIRDS IS REVEALED BY FLIGHT PATHS IN AUSTRALIAN ART, FINANCIAL REVIEW, SATURDAY 25TH OF NOVEMBER, 2016

LOUISE JENNISON, HOW TO BIND A CONCERTINA, WORKSHOP FOR VCE ART AND STUDIO ART STUDENTS AS PART OF FOLIO DEVELOPMENT, IN CONJUNCTION WITH BIRDS: FLIGHT PATHS IN AUSTRALIAN ART

PRATTLING AND CHIRRUPING,

IN CONVERSATION WITH SARA SAVAGE, PARALLEL LINES, RRR, WEDNESDAY 7TH OF DECEMBER, 2016

AND

IN CONVERSATION WITH STEFANIE KECHAYAS, ARTS WEEKLY, 3MBS, SATURDAY 26TH OF NOVEMBER, 2016

ARTSPACE MACKAY

RELATED POSTS,

BIRDS, WE’RE CURIOUS FANS

PRATTLED

SPROUTING WINGS

TRUE OR FALSE?

STILL SPARKIN'

WITHIN A MUSEUM; WITHIN A GALLERY

A GLEAM IN THE DARKLING WORLD

IN THE LIBRARY, A HERD OF SUPERB FAIRY-WRENS

THAT WAY, THICKET

"LOST IN A WILDERNESS OF LISTENING LEAVES"

PRATTLE, SCOOP, TREMBLING

FROM MEMORY

WINGED WITHIN (IN ORDER OF APPEARANCE)

Crimson rosella (Platycercus elegans)

Eclectus parrot (Eclectus roratus)

Australian golden whistler (Pachycephala pectoralis)

Bennets cassowary (Casuarius bennetti)*

Superb fairy-wren (Malurus cyaneus)

Splendid fairy-wren (Malurus splendens)

Red-backed fairy-wren (Malurus melanocephalus)

White-winged fairy-wren (Malurus leucopterus)

Australian magpie (Cracticus tibicen)

Brown honeyeater (Lichmera indistincta)

Australian king-parrot (Alisterus scapularis)

Rainbow lorikeet (Trichoglossus moluccanus)

Little penguin (Eudyptula minor)

Emu (Dromaius novaehollandiae)

Crested pigeon (Ocyphaps lophotes)

Australian ringneck (Barnardius zonarius)

Budgerigar (Melopsittacus undulatus)

Painted buttonquail (Turnix varius)

Superb fruit dove (Ptilinopus superbus)

Rose-crowned fruit dove (Ptilinopus regina)

Cockatiel (Nymphicus hollandicus)

Magnificent riflebird (Ptiloris magnificus)

Greater painted-snipe (Rostratula benghalensis)

Australian pied oystercatcher (Haematopus longirostris)

Yellow-rumped thornbill (Acanthiza chrysorrhoa)

Laughing kookaburra (Dacelo novaeguineae)

Brown cuckoo-dove (Macropygia amboinensis)

Noisy pitta (Pitta versicolor)

Torresian imperial pigeon (Ducula spilorrhoa)

Diamond dove (Geopelia cuneata)

Grey shrikethrush (Colluricincla harmonica)

Southern cassowary (Casuarius casuarius)

Brown falcon (Falco berigora)

Wedge-tailed eagle (Aquila audax)

Prattle, scoop, trembling: a flutter of Australian birds

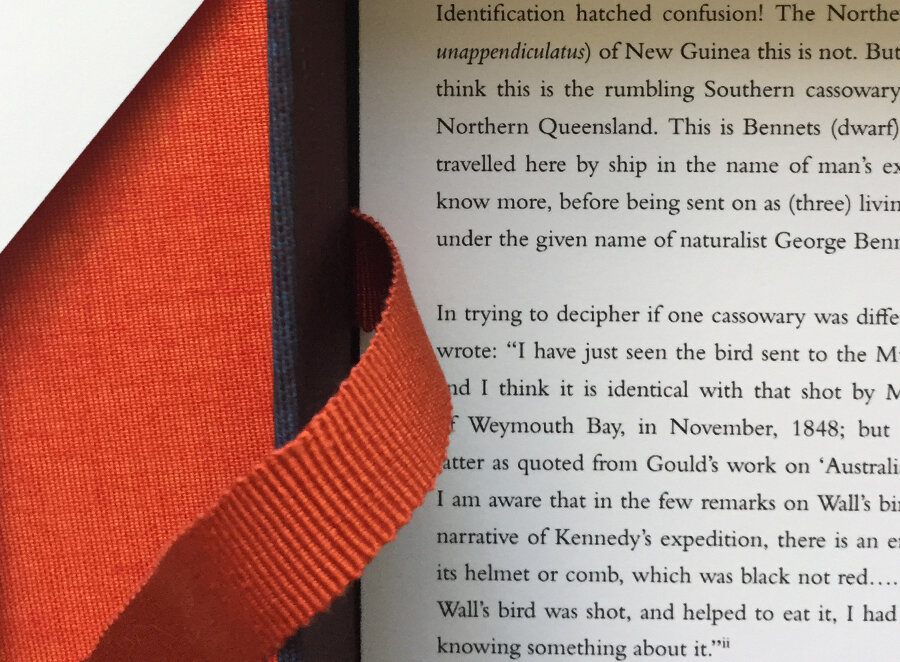

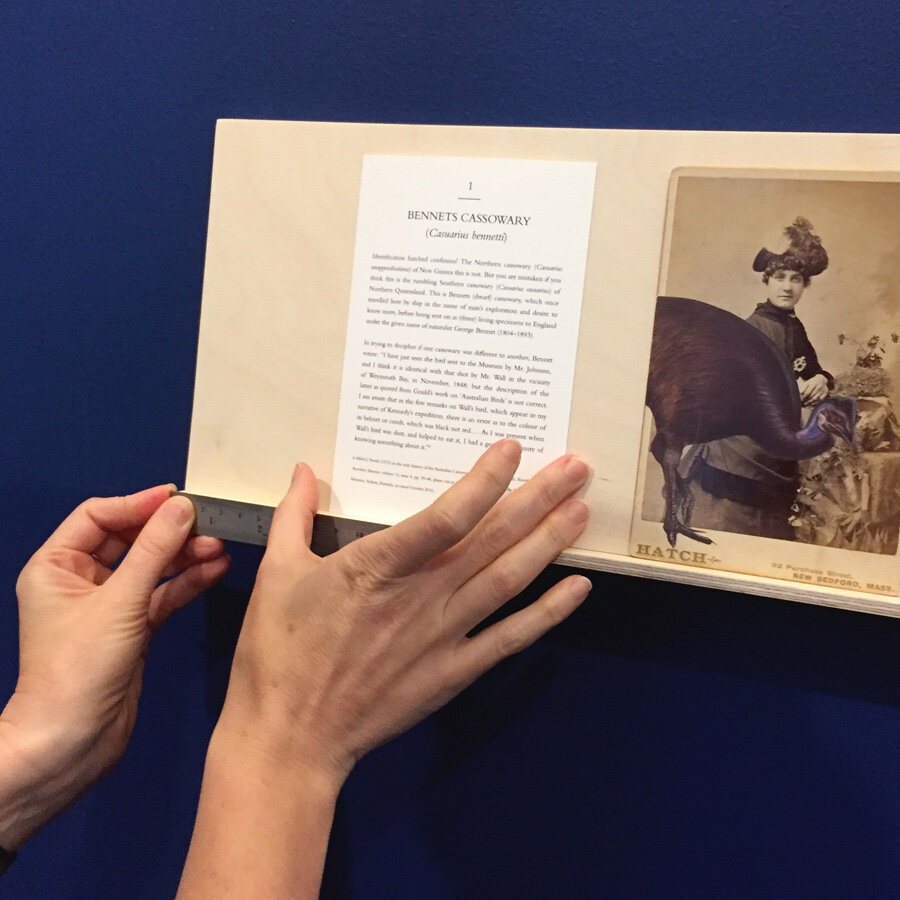

Bennets cassowary (Casuarius bennetti)

Identification hatched confusion! The Northern cassowary (Casuarius unappendiculatus) of New Guinea this is not. But you are mistaken if you think this is the rumbling Southern cassowary (Casuarius casuarius) of Northern Queensland. This is Bennets (dwarf) cassowary, which once travelled here by ship in the name of man’s exploration and desire to know more, before being sent on as (three) living specimens to England under the given name of naturalist George Bennet (1804–1893).

In trying to decipher if one cassowary was different to another, Bennet wrote: “I have just seen the bird sent to the Museum by Mr. Johnson, and I think it is identical with that shot by Mr. Wall in the vicinity of Weymouth Bay, in November, 1848; but the description of the latter as quoted from Gould’s work on ‘Australian Birds’ is not correct. I am aware that in the few remarks on Wall’s bird, which appear in my narrative of Kennedy’s expedition, there is an error as to the colour of its helmet or comb, which was black not red…. As I was present when Wall’s bird was shot, and helped to eat it, I had a good opportunity of knowing something about it.”[i]

[i] Alfred J. North (1913) on the early history of the Australian Cassowary (Casuarius australis, Wall), Records of the Australian Museum, volume 10, issue 4, pp. 39–48, plates viii–ix [19th April 1913], published by the Australian Museum, Sydney, Australia, accessed October 2016.

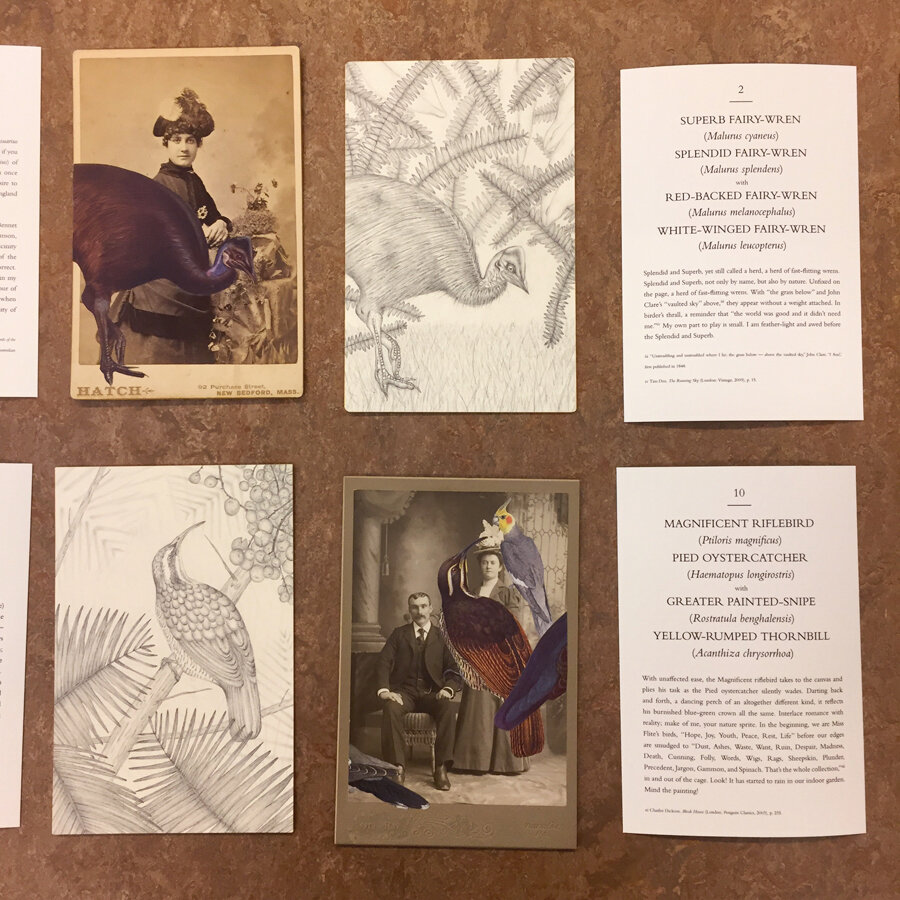

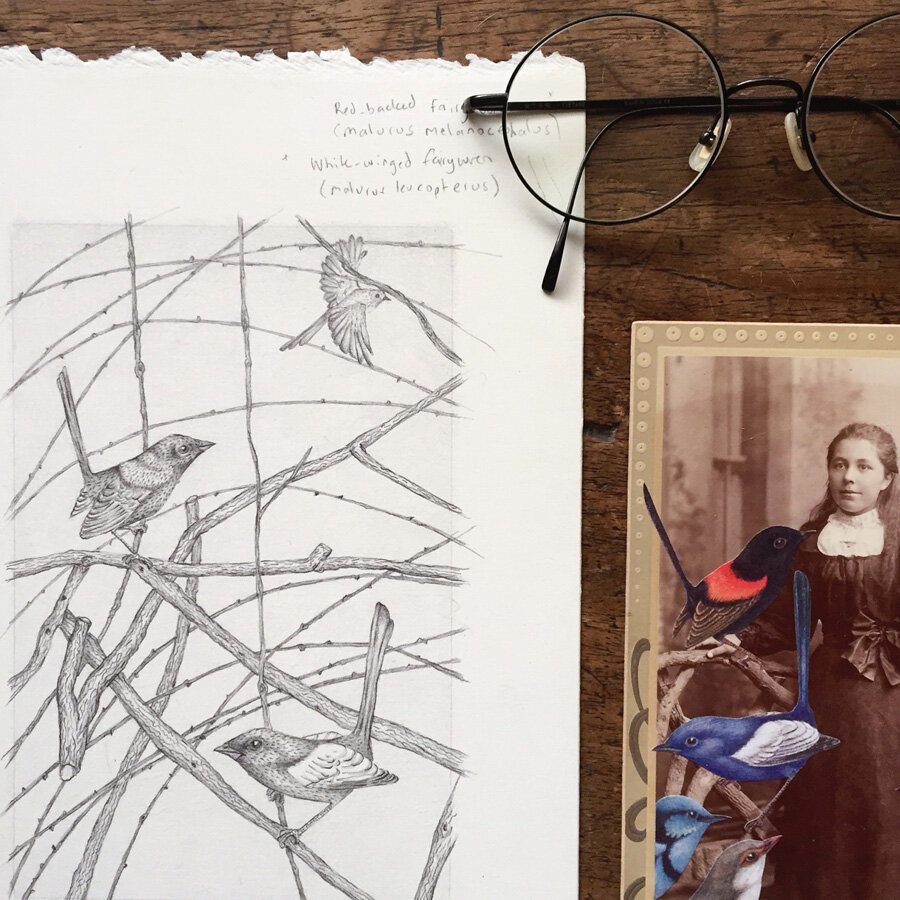

Superb fairy-wren (Malurus cyaneus)

Splendid fairy-wren (Malurus splendens)

with

Red-backed fairy-wren (Malurus melanocephalus)

White-winged fairy-wren (Malurus leucopterus)

Splendid and Superb, yet still called a herd, a herd of fast-flitting wrens. Splendid and Superb, not only by name, but also by nature. Unfixed on the page, a herd of fast-flitting wrens. With “the grass below” and John Clare’s “vaulted sky” above,[i] they appear without a weight attached. In birder’s thrall, a reminder that “the world was good and it didn’t need me.”[ii] My own part to play is small. I am feather-light and awed before the Splendid and Superb.

[i] “Untroubling and untroubled where I lie; the grass below — above the vaulted sky,” John Clare, ‘I Am!,’ first published in 1848.

[ii] Tim Dee, The Running Sky (London: Vintage, 2009), p. 15.

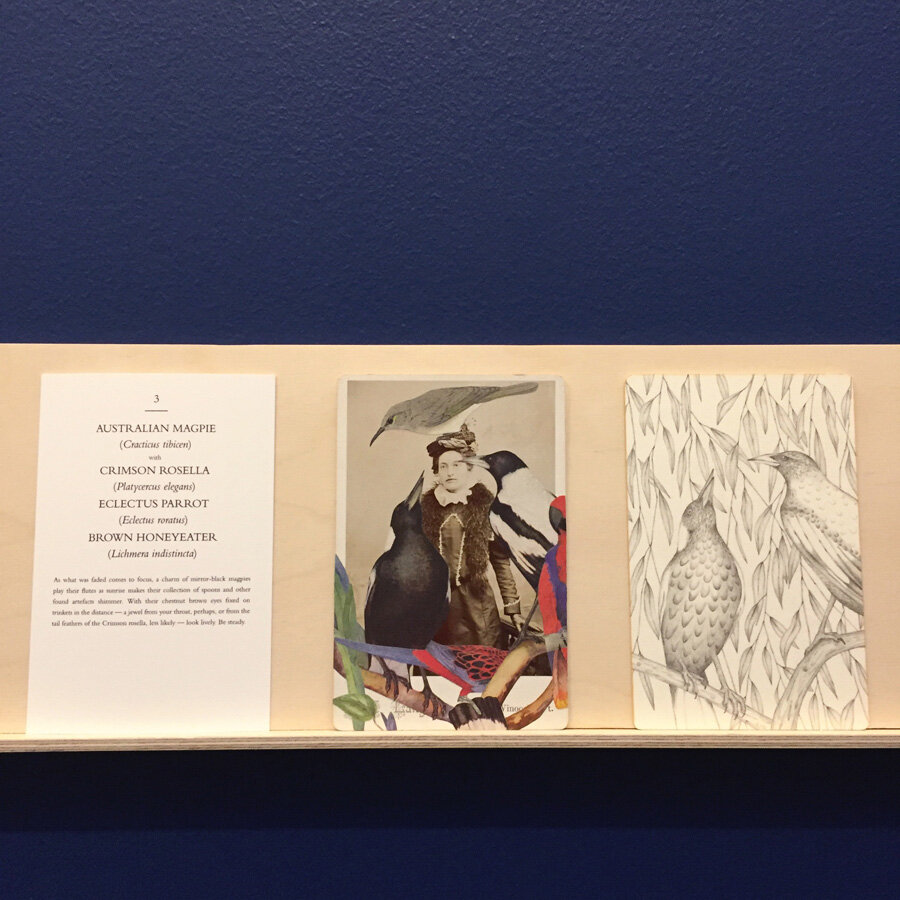

Australian magpie (Cracticus tibicen)

with

Crimson rosella (Platycercus elegans)

Eclectus parrot (Eclectus roratus)

Brown honeyeater (Lichmera indistincta)

As what was faded comes to focus, a charm of mirror-black magpies play their flutes as sunrise makes their collection of spoons and other found artefacts shimmer. With their chestnut brown eyes fixed on trinkets in the distance — a jewel from your throat, perhaps, or from the tail feathers of the Crimson rosella, less likely — look lively. Be steady.

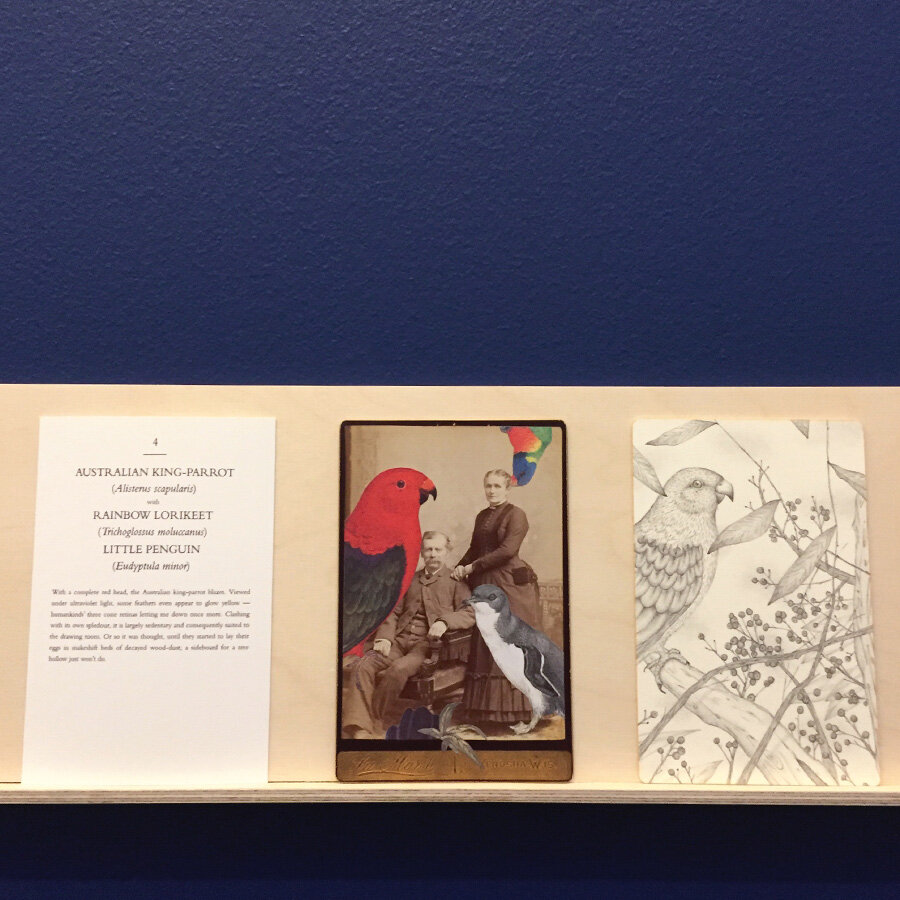

Australian king-parrot (Alisterus scapularis)

with

Rainbow lorikeet (Trichoglossus moluccanus)

Little penguin (Eudyptula minor)

With a complete red head, the Australian king-parrot blazes. Viewed under ultraviolet light, some feathers even appear to glow yellow — humankinds’ three cone retinas letting me down once more. Clashing with its own spledour, it is largely sedentary and consequently suited to the drawing room. Or so it was thought, until they started to lay their eggs in makeshift beds of decayed wood-dust; a sideboard for a tree hollow just won’t do.

Emu (Dromaius novaehollandiae)

with

Crested pigeon (Ocyphaps lophotes)

When carved with a pocket knife and emery board an Emu egg, layered ivory through to darkest blue-green, is perfect for the sideboard’s silverware tableau. Handsome silhouettes can be made to dance around the shell merry-go-round, but I favour the movement found in the weaving, bobbing heads of a mob of emus coming my way. With their shaggy plumage, large black beaks for grazing, and wrinkly hose[i] —New-Holland Cassowary, won’t you come into my parlour? Be my shadow, and play gosling to my Konrad Lorenz.[ii]

[i] “….stepping warily down the path in dark wrinkled stockings and shabby mini fur coats….,” Chris Wallace-Crabbe, ‘Emus,’ Selected Poems 1956–1994, published 1995, Australian Poetry Library, accessed October 2016.

[ii] Nobel Laureate Konrad Lorenz (1903–1989) studied the behaviour of ‘imprinting’ with a hand-reared brood of goslings who took to him like a foster carer. Lorenz is shown in several photographs with a brood of goslings for a shadow.

Australian ringneck (Barnardius zonarius)

with

Budgerigar (Melopsittacus undulatus)

Aviary escapees — one, two, budgerigar — the Australian ringnecks softly chatter and whistle, if you’ll lend an ear or otherwise. Skirting the cultivated garden, so wildly majestic! Their bodies trace a memory recalled only through flight. And I, weighted to the ground, in echo of John James Audubon (1785–1851), feel their close “pass[ing] like a thought…. On trying to see it again [my] eye searches in vain; the bird[s are] gone.”[i]

[i] John James Audubon (1813) on the Passenger pigeon, plate 62 of Birds of America, cited by Tim Dee, The Running Sky, p. 250.

Painted buttonquail (Turnix varius)

with

Superb fruit dove (Ptilinopus superbus)

From John Latham (1740–1837) naming you the latin for ‘various’ ‘partridge’ to John Gould (1804–1881) borrowing from the Greek for ‘half-foot,’ in reference to your lack of hind toe, a ‘sparkling’ ‘half-foot,’ no less, you’ve answered to many, little Painted buttonquail. Come closer; I’ll not let you stand upon bare limestone.[i] Come closer; I’ve a garment to fasten, buttonhole-buttonquail.

[i] Sue Taylor, John Gould’s Extinct and Endangered Birds of Australia (Canberra: National Library of Australia, 2012), p. 114.

Superb fruit dove (Ptilinopus superbus)

Rose-crowned fruit dove (Ptilinopus regina)

The Rose-crowned fruit doves bow their heads, and emit a soft-pitched coo. The Superb fruit dove too. As parson-naturalist Gilbert White (1720–1793) quite rightly penned: “the language of birds is very ancient, and, like other ancient modes of speech, very elliptical; little is said, but much is meant and understood.”[i] Their song so sweet, I am obliged to quit my chamber. Us all, untamed, for now, coo coo.

[i] Gilbert White, excerpted from ‘Letters to the Hon. Daines Barrington,’ Letter 43, The Natural History of Selborne (London: Penguin Classics, 1995), ed. Richard Mabey, p. 191.

Magnificent riflebird (Ptiloris magnificus)

with

Cockatiel (Nymphicus hollandicus)

With your Grecian feathered nose (Ptiloris) tied to a (common name) uniform, you are not drab to me. Rather, you are, we are, all, “the blue sky, [and] the brown soil beneath” of ornithologist W. H. Hudson (1841–1922). “….the grass, the trees, the animals, the wind, and rain, and stars are never strange to me; for I am in and of and am one with them; and my flesh and the soil are one, and the heat in my blood and in the sunshine are one, and the winds and the tempests and my passions are one. I feel the ‘strangeness’ only with regard to my fellow men, especially in towns, where they exist in conditions unnatural to me, but congenial to them.... In such moments we sometimes feel a kinship with, and are strangely drawn to, the dead, who were not as these; the long, long dead, the men who knew not life in towns, and felt no strangeness in sun and wind and rain.”[i]

That is no feather in my hat, but one sprouting from my crown; my shoulders too. Your wings, me.

[i] W. H. Hudson (1906), cited by H. E. Bates, ‘Introduction,’ in Green Mansions: A Romance of the Tropical Forest (London: Collins, 1957), p.15.

Magnificent riflebird (Ptiloris magnificus)

Australian pied oystercatcher (Haematopus longirostris)

with

Greater painted-snipe (Rostratula benghalensis)

Yellow-rumped thornbill (Acanthiza chrysorrhoa)

With unaffected ease, the Magnificent riflebird takes to the canvas and plies his task as the Pied oystercatcher silently wades. Darting back and forth, a dancing perch of an altogether different kind, it reflects his burnished blue-green crown all the same. Interlace romance with reality; make of me, your nature sprite. In the beginning, we are Miss Flite’s birds, “Hope, Joy, Youth, Peace, Rest, Life” before our edges are smudged to “Dust, Ashes, Waste, Want, Ruin, Despair, Madness, Death, Cunning, Folly, Words, Wigs, Rags, Sheepskin, Plunder, Precedent, Jargon, Gammon, and Spinach. That’s the whole collection,”[i] in and out of the cage. Look! It has started to rain in our indoor garden. Mind the painting!

[i] Charles Dickens, Bleak House (London: Penguin Classics, 2003), p. 235.

Laughing kookaburra (Dacelo novaeguineae)

with

Brown cuckoo-dove (Macropygia amboinensis)

At dawn, a kookaburra chorus, inside the house and outside. Those terrestrial tree kingfishers, Spangled and Rufous-bellied. Such a clattering! Rattling order. Shaking our tamed nature pockets. Soiling the parquetry flooring.

Turning the circle of seasons in his hands, H. E. Bates (1904–1974) noted: “there must, it seems, be a closeness, an untidiness, a wildness. There must be all kinds of trees, all kinds of flowers and creatures, a conflicting and yet harmonious pooling of life. A wood planted…. with one kind of tree, has no life at all.”[i]

You cannot rustle up a ‘wildness’ or replant what has been lost.

Rattle order.

[i] H. E. Bates, Through the Woods: The English Woodland — April to April (Dorset: Little Toller Books, 2011), p. 141.

Noisy pitta (Pitta versicolor)

A (rare) visiting Blue-winged? Ethel A. King,[i] I fear you are mistaken. A native Red-bellied or Rainbow, perhaps. A Noisy pitta, more than likely, though something’s not quite right. From what specimen did you work? There should be iridescent blue epaulettes upon a dark green mantle. Let’s return to the scrub and see. Let’s listen for the hammering of snails. To the loud and mournful call: keow, keow, keow. In the subtropical, we’ll wet our feet, and write a sonnet or three.

Whether in dry forest or a rainforest, nature will not be our backcloth, but, like Thomas Hardy, our protagonist. Nature: a living entity in itself. A gleam in the darkling world: “some blessed hope,” trembling.

“Wake and understand…. A stirring thrills the air.”[ii]

[i] Illustration of a Noisy pitta by Ethel A. King from the ‘Weekly Times Wild Nature Series’, supplement to The Weekly Times, 1934.

[ii] Thomas Hardy’s ‘The Darkling Thrush,’ and ‘Spirit of the Pities,’ The Dynasts, cited by Frances Wentworth Knickerbocker, ‘The Victorianness of Thomas Hardy,’ The Sewanee Review, volume 36, no. 3, 1928, pp. 310–325, JSTOR, accessed November 2016.

Torresian imperial pigeon (Ducula spilorrhoa)

with

Diamond dove (Geopelia cuneata)

Grey shrikethrush (Colluricincla harmonica)

The door left open, I hear the soft sounds of the Torresian imperial pigeon — roost awhile, won’t you? This dwelling, this ‘unseasonable heat,’[i] is not yet our tomb, Mary Shelley, but it is close. Linger with me before you fly off in search of the Marianne North Tree[ii] to the east of the Heartbreak Trail.

[i] Mary Shelley, The Last Man, 1826, cited by James C. McKusick, ‘Romanticism and Ecology,’ The Wordsworth Circle, volume 28, no. 3, summer 1997, p. 123, JSTOR, accessed October 2016.

[ii] Botanical artist Marianne North (1830–1890) painted a tall karri tree skirted by a burl in the Warren National Park, near Pemberton. The painting, Karri Gums near the Warren River, West Australia, can be seen in the Marianne North Gallery at Kew Gardens, London, and the tree, to human eyes, appears unchanged by the century and a burl of decades.

Southern cassowary (Casuarius casuarius)

with

Brown falcon (Falco berigora)

The ornithologist Ernest Thomas Gilliard (1912–1965) in his book, Living Birds of the World (1958), described your feet as being “fitted with a long, straight, murderous nail which can sever an arm or eviscerate an abdomen with ease.” But I prefer to see you in quite a different light. In a garden setting, say. And with pencil and glue, that’s just where you’ll stick. There, adhered, I’ll read to you a little of Margaret Gatty’s talkative trees and cobwebs (Parables of Nature (1893)). And as I ramble on, perhaps you’ll find the chance to make good your escape. Applying your brilliant spatial memory — that way, thicket.

Wedge-tailed eagle (Aquila audax)

If H is for Hawk, then let E be for Eagle, the largest raptors in the sky above, with wings like long grasping fingers, and pinkish gape. The Wedge-tailed eagle, sharp by name and disposition — continue your depredations! — spies a caged silktail (Lamprolia victoriae) and wonders how it came to be there. A “curious little creature,”[i] the silktail, shimmied from place amongst the birds-of-paradise (Paradisaeidae), the Australian robins (Petroicidae), the fairy-wrens (Maluridae), and now here, in the field notes of the hallway. An unexpected diminutive silktail far from home, do my eyes deceive me? As the eagle pipes psee-eew, psee-eew, psee-eew, their conversation is likely to be short.

With strength of wing and clarity of sight, “what we see in the lives of animals are lessons we’ve learned from the world.”[ii] With eyes yet to cloud over and wings singed by the edge of the sun, “you too, mankind, are like this.”[iii]

[i] Otto Finsch (1873), On Lamprolia victoriae, a most remarkable Passerine Bird from the Feejee Islands, Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London, pp. 733–735.

[ii] Helen Macdonald, H is for Hawk, (London: Random House, 2014), p. 60.

[iii] ’The Eagle,’ Peterborough Bestiary MS53, early 14th century, cited by Graeme Gibson, The Bedside Book of Birds: An Avian Miscellany (London: Bloomsbury, 2005), p. 323.

Milly Sleeping: Quick Interview with Gracia Haby of Gracia & Louise

True or False?

2017

Our final interview for the holiday period evolved into a 'true or false' quiz for Melbourne-based artists Gracia Haby and Louise Jennison, AKA Gracia & Louise. Together and independently (but most often together, and most often with a four-legged friend or two), G + L are very prolific makers, doers, dreamers — delightful to follow on the gram. The image above is from their new artists' book, Prattle, scoop, trembling: a flutter of Australian birds, 2016 — which is currently on display at the Mornington Peninsular Regional Gallery. Kind thanks to Gracia for taking the time to write, and to both she and Louise - for always being willing partners to our projects and flights of fancy.

True or false, Louise draws all the animals and Gracia creates the collage?

More true than false. Yes, Louise is at home with a 2B Staedtler pencil and a brush for colour wash, whilst I prefer a small pair of scissors, and my brush is for dipping in the glue jar. Our digital collages are a fusion of both, though they are created in similar layered vein to those created through fine cut and paste.

You've been creating and making for some time now?

True that, too. We’ve been making artists’ books together since 1999. Upon last count, we’ve released 87 titles (unique state artists’ books, and limited editions of 10, 25, and 50). How we work together has slowly changed to accommodate our ideas and we have distinct roles. However whilst these roles are distinct, they are above all flexible. Ultimately, whatever the work needs is how the roles are shaped. Our collaboration is as organic as it is fastidious, and it is founded in harmony.

You currently have work on display in an exhibition at the Mornington Peninsula Regional Gallery, entitled Birds: Flight paths in Australian art?

True. Indeed we do. Until the 12th of February, 2017, you can see our artists’ book, Prattle, scoop, trembling: a flutter of Australian birds on the gallery wall. In this piece, Louise’s drawings are created in response to the collage pieces. Hence, an Australian king-parrot (Alisterus scapularis) seen resting upon a man’s knee in a cabinet card composition, in the drawing appears within splendid foliage of red berries. In addition to this piece, we also have a print, Underneath Soane’s ‘star-fish’ ceiling, the library at No. 12 proved anything but quiet (2016), and Louise’s artists’ book, A Flight of Twelve Southern Hemisphere Birds (2013).

You have, full-time, two cats and one dog (but perhaps a few others on the books)?

True. We have Olive (11-year-old black and white cat), Lenni (2-year-old Siamese cat), and Lottie (3-year-old Jack Russell terrier with the pins of an Italian greyhound). We also shelter Misha (11-year-old tabby), and care, with a neighbour, for Frank (9-year-old ginger tom), both of whom were abandoned. And two kittens we’ve nicknamed Trouble and Squeak come over to play in our back garden. A back garden that is also home to an elderly singing canary, and visiting bird (rainbow lorikeets, doves, and sparrows) and possum (brush and ringtail) life.

One of you used to dance and sort of still does?

True. Many moons ago now I donned a leotard and undertook classical ballet training through until late Secondary School years. Now I get to sit still and see a lot of dance, and later write about it for Fjord Review. And if hand weights in first position count, Barre Body classes for the head and the heart.

One of you is a very competent/confident home DIY-er?

True. Louise is brilliant with a spot of maintenance and property upkeep. Replacing washers, unblocking sinks, sawing branches, patching gutters, minor rewiring, replacing floorboards…. hovering the roof, polishing the chimneys, you name it. Must be that Art School resourcefulness coming into play.

You are both really looking forward to 2017?

True. True. Absolutely. Again. Here’s to a year with more of the good and challenging bits! For you, us, everyone.

And to help make it so, in something of a growing tradition, from all of us here to all of you there, chime and chirrup, sniff and purr along with the menagerie. From Olive, Lenni, Lottie, Misha, Frank, a singing canary named Tim, visiting Rainbow lorikeets, and the possums, Ring and Brush, too, a safe and happy 2017 one and all.