A VELVET ANT, A FLOWER AND A BIRD

Potter Museum of Art commission for A velvet ant, a flower and a bird, 2026

Selected references

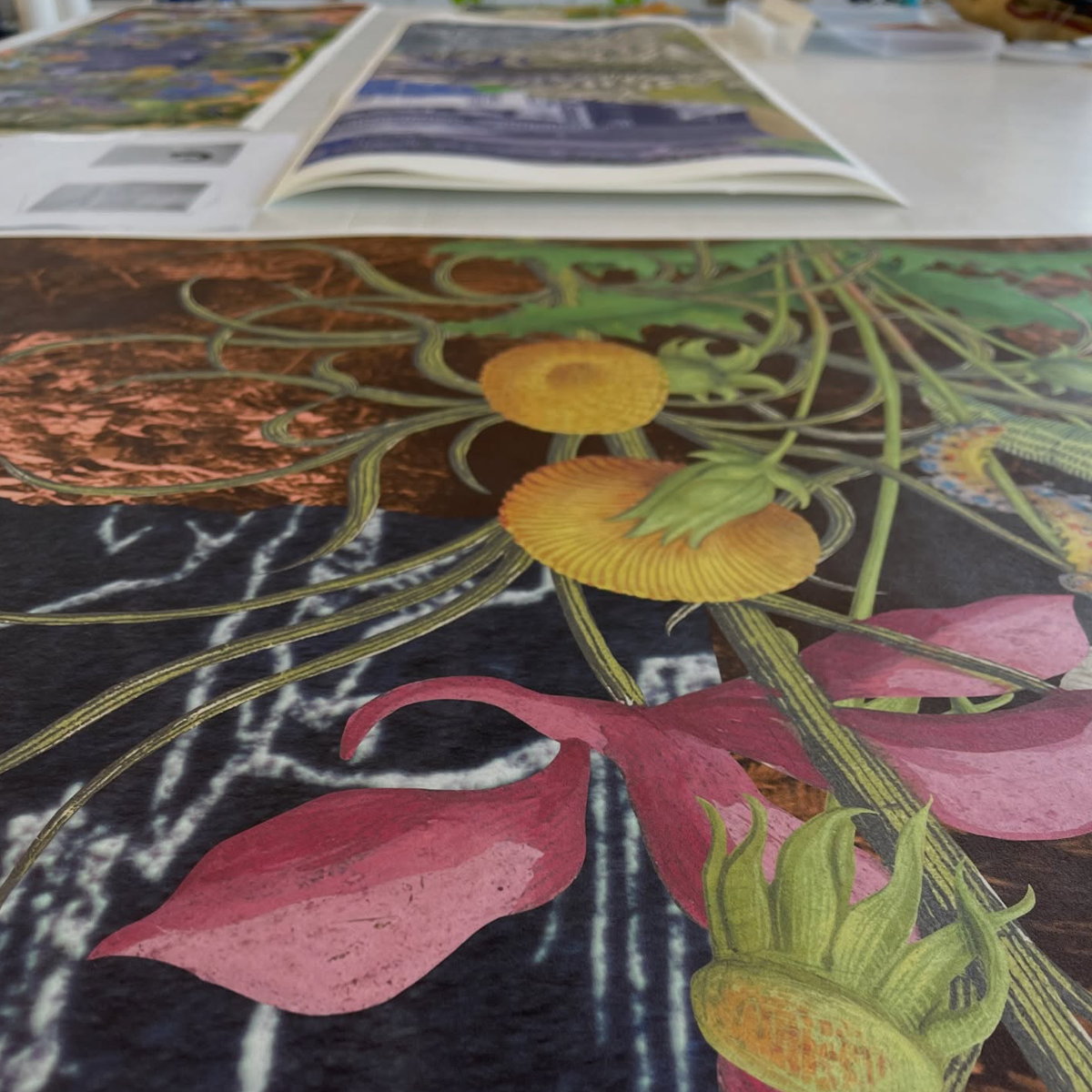

Selected pieces within the collage

Gracia Haby & Louise Jennison

Specimen 1963

2026

A Potter Museum of Art commission for A velvet ant, a flower and a bird exhibition curated by Chus Martínez

Thursday 19th of February – Saturday 6th of June, 2026

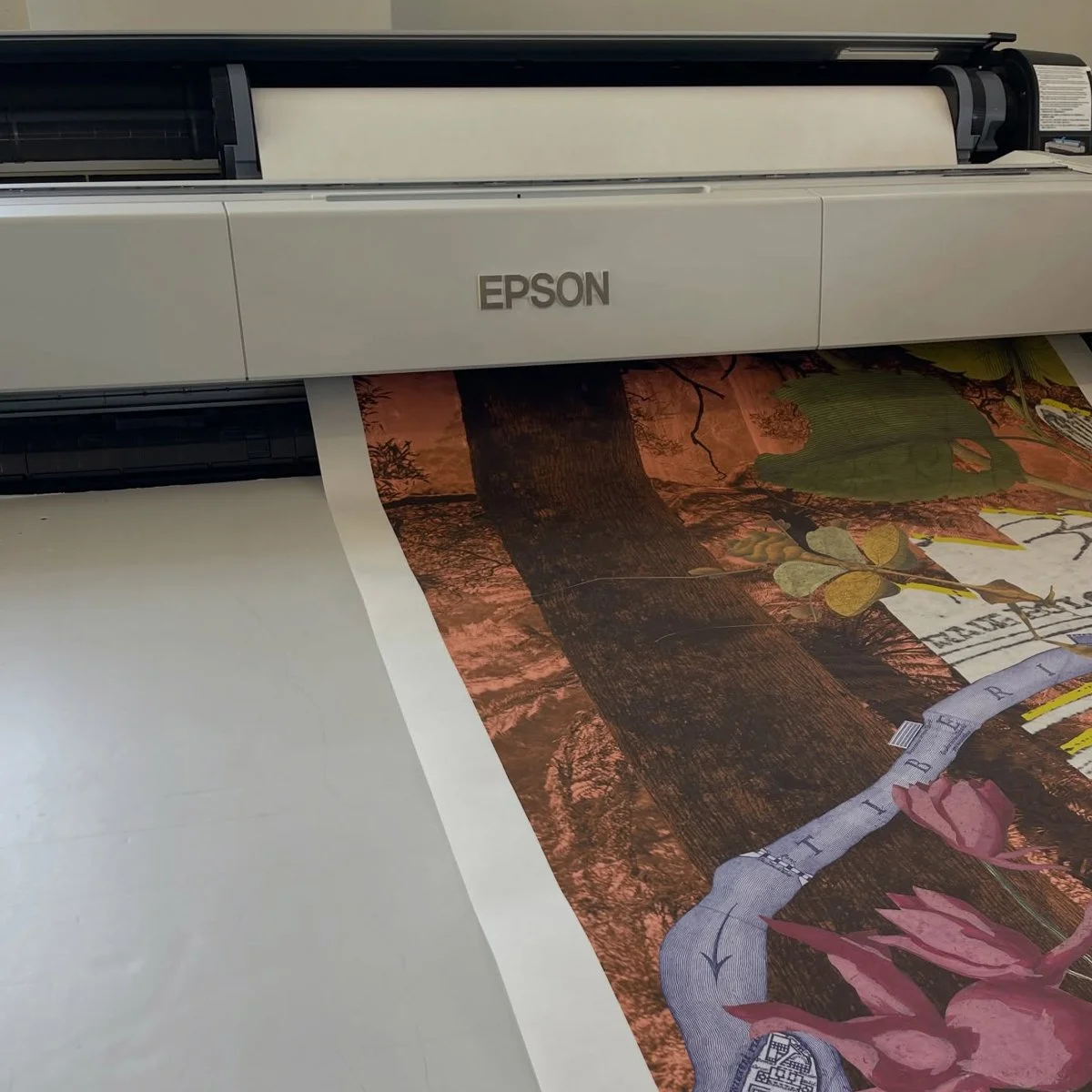

Inkjet print on Moenkopi Kozo 110 with pencil additions

Printed by Arten, suspended concertina ply frame fabricated by Arten

A Velvet ant by name, a wasp by family, so visual and textural is the image conjured. An ant who is a wasp. A wasp who is soft. Who decided this was so? Do the Velvet ants agree?

From a family, worldwide, Mutillidae number in excess of 7,000 species, and that is just the ones that we humans know about and have recorded. The Velvet ant is named after the wingless appearance of the female, who resembles, it was decided, a hairy, velvety ant. But don’t let the velvet part confuse you, like the ant component may. The Velvet ant sports armour. Armour so strong it is known to break the pins of entomologists. It is what is needed, this armour, if you are going to locate the nest of another type of wasp or bee and, once inside, lay your single egg on the larvae of the host insect. If you were to be intercepted, you’d require armour too; your plans run counter to each other.

As Dr Ken Walker, Senior Curator of Entomology, Museums Victoria Research Institute, revealed to us, the Velvet ant is awe-inspiring. Looking at a single specimen beneath the microscope, she peered back at us, a dimorphic beauty, collected in 1963, but fantastically present. Magnified upon the screen, her striated thorax resembled amber glass. Atop her head, her GPS-like lens, which allowed her to see in ultraviolet and polarised light, could be seen, and duly dreamed. And her compound eyes that allowed her to see 300-frames-per-second, a level of detail inconceivable for us to fathom. Next to her, we move in slow motion, for wasps, evolutionary speaking, are so far advanced, when compared to ourselves.

Charmed by Jan Swammerdam’s (1637–1680) introduction to his The Book of Nature; (or [extended title], The History of Insects reduced to distinct classes, confirmed by particular instances, displayed in the anatomical analysis of many species, and illustrated with copper-plates), this work is our approximation of a single female Velvet ants umwelt. Her umwelt, ‘Specimen 1963’. Like Swammerdam, “Curious reader, before [we] proceed to lay [our] observations before you, [we] must most humbly request, that you will not be displeased, if in all this work [we] have only made use of [our] own observations”. Where Swammerdam offered this “as a solid and immoveable foundation to build upon,” and from which “deduced certain conclusions, solid theorems, and classes digested in due order”, we offer imaginings to the world as it is experienced by ‘Specimen 1963’.

In that world, there are many potential hosts. There is a central nest, where her one egg rests. There are tunnels to the nest, where she has chewed her way in. Buoyed by the work of Maria Sibylla Merian (1647–1717), together with daughters, Dorothea Maria and Johanna Helena, in which the life cycles of insects, moths and butterflies were depicted on the page, we have followed suit. Where Merian recorded the activities alongside the local flora and fauna — insects with their host plants, interactions between same and different taxa, food chains — and in doing so laid bare the connection of all things, in our work, we invite you to marvel at the ingenuity of her path (Merian, Velvet ant, both). To revel in the translucency of the wings of bumblebees, for though they are drawn, they’re still capable of flight! To shrink your own form, and see the world anew. Inspired by the concept of Charles Frederick Holder’s (1851–1915) Half hours in the tiny world: wonders of insect life, tilt your head to the side and wonder at this ‘tiny world’ writ large.

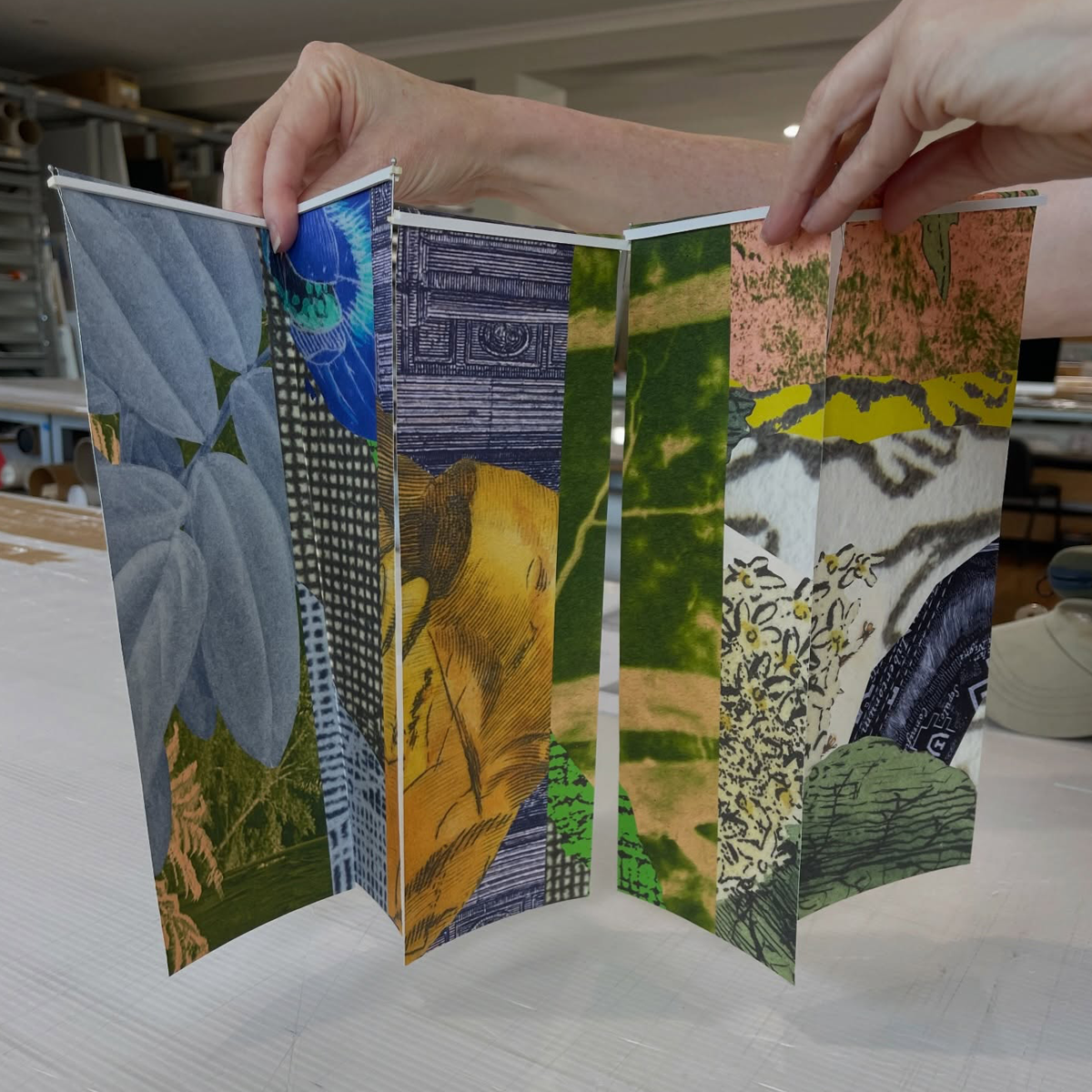

A ‘tiny world’ of a digital collage composed across a series of suspended screens, 8 metres in length and 2.8 metres high. Our floating concertina consists of eight individual drops, hanging through tension by a timber mechanism. And like the Velvet ant’s antennae, which enable her to smell her world and in doing so add to her understanding of it, this series of screens is responsive; it can compress or extend within the space, altering the angle and, thereby, the visual relationships. An archival inkjet print on Moenkopi Kozo 110, a Traditional Japanese Washi paper, there is also a hint of a wing-like transparency to the pages of Specimen 1963.

And just why does this piece float from the floor? Because, prior to the Velvet ant laying her egg in a suitable host’s nest, after consummation with the winged male, he lifts her from the ground so that she can reach the protein source — the sugary nectar of flowers she’d ordinarily not be able to reach in this manner — she needs for her egg. A romanticised visual, a floral ascent, but what of it, “curious reader”.

Included within the collage, you will find beetles and gnawed leaves from Casper Stoll’s Natuurlyke en naar ‘t leeven naauwkeurig gekleurde afbeeldingen en beschryvingen der wantzen, in alle vier waerelds deelen Europa, Asia, Africa en America huishoudende (1788), and Edward Donovan’s, self-described “diversified assemblage of interesting objects” showcased within Natural history of the insects of China: containing upwards of two hundred and twenty figures and descriptions (1842). Having scuttled from the copper plate to the page and off again, insects from Eleazar Albin’s A natural history of English insects (1720) too.

You will find an iridescence of entomological elements from Dru Drury’s Illustrations of exotic entomology: containing upwards of six hundred and fifty figures and descriptions of foreign insects, interspersed with remarks and reflections on their nature and properties (1837); William Houghton’s Sketches of British insects: a handbook for beginners in the study of entomology (1875); James Duncan’s The natural history of beetles (1835) and The natural history of foreign butterflies (1837); R. J. Tilyard’s The insects of Australia and New Zealand (1926); M. James Thompson’s Archives entomologiques, volumes 1 and 2 (1857–1858), and more besides.

From the Australian Museum collection of minerals, we have traced outlines to form her landscape. It is comprised of Dante and Piranesi, but in the shape, now, of Azurite, Angelsite, Cuprite on Calcite, and shafts of Rhodochrosite. Because the world ‘Specimen 1963’ understands is as vast as it is, we fancy, saturated.

Our research into the Velvet ant led us to the collections of the Baillieu library, State Library Victoria (SLV), and Melbourne Museum, specifically. With terrific thanks to Susan Millard, Curator of Rare Books, at The University of Melbourne; Dr Anna Welch, Principal Collection Curator, History of the Book, State Library Victoria; and Hayley Webster, Manager, Library, Museum Victoria for showing us your collections and ensuring we remained beholden to luminous encasements and furred antennae. Thank-you for having parts of your respective collections digitised especially for this project, or providing access to earlier digitised files of the exquisiteness that lies within the casing of book covers. Thank-you, also, to your digitisation team colleagues for their work photographing, scanning, and imaging the extraordinary wealth of material within this selection of rare books pertaining to natural history with an emphasis on entomology.

In addition to the earlier sources referenced, we drew inspiration from a Book of Hours from the southern Netherlands, c.1490; and a Pontifical made for Philippe de Levis, the Bishop of Mirepoix, Paris, c. 1520, in the collection of SLV, with the fantastical insects awaiting deciphering in the marginalia. A World of Wonders Revealed by the Microscope: a book for young students with coloured illustrations by the Hon. Mrs. Ward (1859), a charm within the Baillieu, added to our understanding. Editions withing SLV, the Baillieu, and Melbourne Museum of John Abbot and Sir James Edward Smith’s The natural history of the rarer lepidopterous insects of Georgia : including their systematic characters, the particulars of their several metamorphoses, and the plants on which they feed (1797); Jacob Hübner and Carl Geyer’s Sammlung exotischer Schmetterlinge (1806); and J. O. Westwood’s Arcana entomologica; or illustrations of new, rare and interesting insects (1845) illuminated our awareness.

There are over 1.05 million insect species in the world, and you, Susan, Anna, Hayley, and Ken have shown us a great many of them. Thank-you.

Thank-you, Chus Martínez, and all at the Potter Museum of Art, for this glorious opportunity to delve into the world of the Velvet ant for as long as she’ll have us, or rather, for as long as it remains safe for us to do so; her sting is mighty, and her tale is humbling. Thank-you.

Borrowing once more from Merian, who upon the preface to The transformation of the insects of Suriname declares this as being for both ‘lovers of art’ and ‘lovers of insects’, we devote this to such lovers. May the Velvet ant be your portal to the wide beyond.

﹏

RELATED LINKS,

POTTER MUSEUM OF ART, UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE

A VELVET ANT, A FLOWER, AND A BIRD

RELATED POSTS,

IN THE WINGS

SPECIMEN 1963

TINY JANUARY

ON WALL, ON SCREEN, FORMED, AND FORMING

TINY DECEMBER

WE ARE CREATURES OF ORGANIC SUBSTANCE

SLOW. QUICK. SLOW.

A PAPER UNIVERSE EXPANDS IN THE LIBRARY

LOOK CLOSER

NOW AND WINGED

MARVELS, TAILED AND WINGED

MICROSCOPIC RECREATIONS

Velvet ants (Hymenoptera: Mutillidae) are solitary insects and they exhibit extreme sexual dimorphism. While the winged males have no sting and typically have a less conspicuous colouration than the females, the latter are wingless, actively search the ground, or trees, in some cases, for hosts and are notorious for their painful sting.

Selected references

John Abbot, The natural history of the rarer lepidopterous insects of Georgia : including their systematic characters, the particulars of their several metamorphoses, and the plants on which they feed, 1797

Eleazar Albin, A natural history of English insects,1720

Edward Donovan, An epitome of the natural history of the insects of China, 1798

Edward Donovan, An epitome of the natural history of the insects of New Holland, New Zealand, New Guinea, Otaheite, and other islands in the Indian, Southern, and Pacific Oceans, 1805

Dru Drury, Illustrations of exotic entomology: containing upwards of six hundred and fifty figures and descriptions of foreign insects, interspersed with remarks and reflections on their nature and properties, Volumes 1 and 3, 1837

James Duncan, The natural history of beetles, 1835

James Duncan, The natural history of foreign butterflies / illustrated by thirty-three coloured plates; with memoir and portrait of Lamarck, 1837

E. J. C. Esper, Die auslandischen Schmetterlinge hrsg. mit Zusatzen und fortgesetzt von T. von Charpentier, 1830

Charles Frederick Holder, Half hours in the tiny world: wonders of insect life, 1905

William Houghton, Sketches of British insects: a handbook for beginners in the study of entomology, 1888

Jacob Hübner and Carl Geyer, Sammlung exotischer Schmetterlinge, 1806–[1841]

William Kirby, Monographia apum Angliae, or, An attempt to divide into their natural genera and families, such species of the Linnean genus Apis as have been discovered in England : with descriptions and observations : to which are prefixed some introductory remarks upon the class Hymenoptera, and a synoptical table of the nomenclature of the external parts of these insects, 2 volumes in 1, 1802

John Lewin, A natural history of the lepidopterous insects of New South Wales, collected, engraved, and faithfully painted after nature, 1822

Hippolyte Lucas, Histoire naturelle de Lepidopteres exotiques, 1845

Maria Sibylla Merian, De europische insecten, naauwkeurig onderzogt, na't leven geschildert. [Bound withl Over de voorttelingen en wonderbaerlyke veranderingen der Surinaamsche insecten, 1730

Caspar Stoll, Natuurlyke en naar 't leeven naauwkeurig gekleurde afbeeldingen en beschryvingen der wantzen, in alle vier weerelds deelen Europa, Asia, Africa en America huishoudende, 1788

Casper Stoll, Natuurlijke en naar het leven nauwkeurig gekleurde afbeeldingen en beschrijvingen der spoken, wandelende, bladen, zabel-springhanen, krekels, trek-springhanen en kakkerlakken, in alle vier deelen der wereld, Europa, Asia, Afrika, en Amerika, huishoudende, 1813

Alexander Scott, Harriet Scott, and Helena Scott, Australian lepidoptera and their transformations, 2 volumes, 1864–1898

Rodolph Stawell, Fabre’s Book of Insects: retold from Alexander Teixeira de Mattos' translation of Fabre's "Souvenirs entomologiques”, 1921

Jan Swammerdam, The book of nature, or, The history of insects : reduced to distinct classes, confirmed by particular instances, 1758

James Thompson, Archives entomologiques; ou recueil contenant des illustrations d’insectes nouveaux ou rares, Volumes 1 and 2, 1857–1858

R. J. Tillyard, The insects of Australia and New Zealand, 1926

Mary Ward, A World of Wonders Revealed by the Microscope: a book for young students with coloured illustrations by the Hon. Mrs. Ward, 1859

J. O. Wetswood, Arcana entomologica; or illustrations of new, rare and interesting insects, 1845

Book of Hours from the southern Netherlands, c.1490

Drawings of lepidopteral by C.M. Curtis, I.H. Newton, G. Samouelle, 1826

Pontifical made for Philippe de Levis, the Bishop of Mirepoix, Paris, c. 1520

Additional References

Deyrup, Mark, and Manley, Donald, ‘Sex-Biased Size Variation in Velvet Ants (Hymenoptera-Mutillidae)’,‘The Florida Entomologist, Vol. 69, No. 2, 1986, pp. 327–335, JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/3494937

Evans, Arthur V., The Little Book of Beetles, Princeton University Press, 2024, JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/jj.7616630

Harman, Oren, Metamorphosis: A Natural and Human History (Great Britain: John Murray Publishers, 2025)

Kershenbaum, Arik, Why Animals Talk: The New Science of Animal Communication (Great Britain: Penguin Books, 2025

McAlister, Erica, with Washbourne, Adrian, Metamorphosis: How Insects Are Changing Our World (Clayton, Victoria: CSIRO Publishing, 2024)

Monsó, Susana, Playing Possum: How Animals Understand Death (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2024)

van Noort, Simon, and Broad, Gavin, Wasps of the World: A Guide to Every Family, Vol. 8, Princeton University Press, 2024, JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/jj.7514501

Olson, Christina, ‘What I Learned From the Velvet Ant’, The Anxiety Workbook: Poems, University of Pittsburgh Press, 2023, p. 51, JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv37mk2g6.28

Richard, Denis, and Maquart, Pierre-Olivier, The Wonder Cabinet of Fabulous Insects (New York: Abrams, 2025)

de Roode, Jaap, Doctors by Nature: How Ants, Apes & Other Animals Heal Themselves (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2025)

Simbeck, Rob, The Southern Wildlife Watcher: Notes of a Naturalist, University of South Carolina Press, 2020, JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvrxk3d7

Swan, Heather, ‘The Forest of Orchids’, Emergence Magazine, 27th May, 2021, https://emergencemagazine.org/essay/the-forest-of-orchids

Wehner, Rüdiger, ‘Polarized-Light Navigation by Insects’,‘Scientific American, Vol. 235, No. 1, 1976, pp. 106–115, JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24950397

Wikelski, Martin, The Internet of Animals: Discovering the Collective Intelligence of Life on Earth (Brunswick, Victoria: Scribe Publications, 2024)

Williams, Kevin A.; Pan, Aaron D.; Wilson, Joseph S., Velvet Ants of North America, Princeton University Press, 2024, JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/jj.5104027

Components within the collage include

Dante Alighieri

Commedia di Dante, Firenze: Per opera & spesa di Philippo di Giunta fiorentino, 1506

Featuring cross sections of Hell, with its famous circles, and maps showing the location of Mount Purgatory, the very first topographical images to accompany Dante’s poem, throughout.

From Eleazar Albin, A natural history of English insects, 1720

A caterpillar “of a pale green, spotted with black… found to frequently on cabbage and cauliflowers from June to September. They feed also on Nasturtium” from the First plate

A “green striped with white” caterpillar “taken in a garden near Hackney… [on] the 14th of June feeding on the Larkspur” from the 27th plate

Two caterpillars, one “of a deep green, its head blueish, the other of a yellowish green, the head of it lighter coloured” on a Bramble from the 30th plate

“The Black Caterpillars… fed in a web together on Black Thorn, White Thorn, and Plumb Tree… found at the latter end of May” from the 70th plate

A “Green Caterpillar on the Neetle, … found at the beginning of August” from the 77th plate

A Caterpillar “spotted with red on the back” from the 99th plate

From Dru Drury, Illustrations of exotic entomology: containing upwards of six hundred and fifty figures and descriptions of foreign insects, interspersed with remarks and reflections on their nature and properties, Volumes 1 and 3, 1837

A Luna moth (Actias Luna) whose “wings are of a beautiful pea-green colour; the nerves being of a pale red brown”, from plate XXIV

A Rainbow scarab (Phaneaus carnifex) from plate XXXV

A pair of Casnonia longicollis, whose “antennae [is] dark brown, about the length of the head and thorax” from plate XLII

Leptoscelis balteatus and Centris surinamensis with a “tongue very long, extending to the middle of the abdomen” from plate XLIII

Jamaican digger wasp (Sphex jamaicensis), a species of thread-waisted wasp in the family Sphecidae, with an “abdomen shining and very smooth, red brown and united to the thorax by a small but short thread-like peduncle”, and Scolia fossulana from plate XLIV

Pelopaeus caementarius “imago* taken out of the cocoon” from plate XLIV

Nest and Section of the Nest of a Pelopaeus ceamentarius, a species of sphecid wasp, who “seek out a proper spot that is secure from rains, &c, and is so situated as to afford a sufficient warmth for the young offspring, but not so hot as to destroy instead of nourish them”, from plate XLV

Twelve-spotted skimmer (Libellula pulchella) from plate XLVIII

A species of praying mantis (Empusa gongylodes) “exactly resembling the colour of a withered leaf”, and a Bacteria linearis, who resembles “a parcel of straws united together… known to collectors as spectres, or walking-stick insects” from plate L

From James Duncan, The Natural History of Beetles, 1835

A King Diving Beetle (Dytiscus dimidiatus) that usually lives in wetlands, from plate IV

A Buprestis Chrysis, and a Buprestis bicolor, a type of metallic wood-boring beetle from plate VI

A Common click beetle (Elater melanocephalus), a Malachius marginellus, a type of soft-winged flower beetle, a Priocera Variegata, which “has curious involuted suckers on its feet” (Kirby, William and Spence, William. 1815–26. An introduction to entomology. 4 Vols. London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, and Green. Vol. 2.) from plate VIII

A Sabertooth longhorn beetle (Prionus cervicornis) from plate XXIII

A Lamia ornata, a Lamia Formosa, an Elderberry borer or Cloaked Knotty-horn beetle (Desmocerus cyaneus), and a Lamia tricincta, a species of longhorn beetle from plate XXVI

James Sowerby

Geology: Amber enclosing a black wasp (Sphex hymenoptera) and two parts with sulphur and pyrites, 1804

Detail from a hand-coloured copper engraving drawn from specimens in Sowerby's personal mineralogical collection. From 1802, Sowerby began to issue by subscription his British Mineralogy, issued in 78 parts with assistance from his sons George and James. Each hand-coloured plate afforded individual subscribers to bind their own collections. A limited number of complete sets were published around 1818. We have purloined this amber orb as representative of ‘Specimen 1963’s’ egg.

From Rodolph Stawell, Fabre’s Book of Insects: retold from Alexander Teixeira de Mattos’ translation of Fabre’s “Souvenirs entomologiques”, 1921

Common wasps, whose “nest is made of a thin, flexible material like brown paper, formed of particles of wood” from p. 144

From Caspar Stoll’s Natuurlyke en naar 't leeven naauwkeurig gekleurde afbeeldingen en beschryvingen der wantzen, in alle vier weerelds deelen Europa, Asia, Africa en America huishoudende, 1788

A Yellow-banded bug (De Geelgebandeerde Wantz)

Java bug (De Javaner)

The Noble bug (De Edele Wantz)

The Fleeceleg (De Vliespoot)

The green and yellow cicada (De Groene en Geele Cicade)

Arthur Streeton

Spring, 1890

Detail from Streeton’s oil on canvas on plywood depicting bathers on a corner of Sill’s Bend on the Birrarung/Yarra River (Banksia Park, Heidelberg).

Giovanni Battista Piranesi

Interior View of the Pantheon (Veduta interna del Panteon, from Vedute di Roma (Views of Rome) ca. 1768

etching on laid paper“Ichnographia” or Imaginary Plan of the Campus Martius, 1762

engraving on paper

Piranesi’s plan of Rome is his Ichnographic Plan of the Campus Martius from 1762, where he depicts a vast cityscape of invented “ancient monuments” to populate an otherwise accurate base map of the city derived from Nolli’s map as a base, features throughout the collage. And the Pantheon has been commandeered for the host insect’s nest.

Composite image of a female Mutillidae, 2026, courtesy of Dr Ken Walker, Senior Curator of Entomology, Museums Victoria Research Institute

From The Book of Flower Studies, created in the workshop of the Master of Claude de France, ca. 1510–1515

Folio 28: Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) with

a caterpillar

* In Entomology, imago in the final and fully developed adult stage of an insect typically winged.

A velvet ant, a flower, and a bird.

The University of Melbourne’s Potter Museum of Art is proud to announce an ambitious new exhibition curated by internationally renowned curator Chus Martínez titled A velvet ant, a flower, and a bird.

Opening 19 February and running until 6 June 2026, the exhibition brings together works from the University of Melbourne’s Classics, Biology, and Art collections, alongside new commissions and performances by acclaimed artists from Australia and abroad.

“This exhibition can be seen as a garden of knowledge, structured around three familiar figures from nature — a velvet ant, a flower, and a bird. These figures represent a parliament of beings, each carrying symbolic and metaphorical weight that encourage us to reimagine what intelligence means”

Historic and contemporary works will be displayed in dialogue, fostering unexpected encounters between the University’s collections and contemporary practice. The exhibition invites visitors to question the divide between natural and artificial intelligence, and to see intelligence as something shared across all living systems and materials, rather than an exclusively human trait.

This expansive curatorial vision explores how museum collections can open space for new ways of reasoning. “In approaching the University’s collections outside conventional academic frameworks, I came to the idea of calling animal wisdom into account,” Martínez explains.

“Collections hold many narratives — historical, cultural, economic, material — and by bringing them into living knowledge systems, we’re able to dissolve the binary between the natural and the artificial. The visitor enters a kind of ecosystem, where objects and digital media exist without hierarchy, allowing the imagination to roam widely.”

The first of these entities is the velvet ant, which Martínez describes as “a wise being, a connoisseur of materials and renewable energies,” who represents radical adaptation — inspired by recent scientific studies into its uniquely light-absorbing structure, which could revolutionise solar technology. The flower, regarded as a “sun-fed intelligence,” symbolises perpetual renewal and adaptive creativity. The bird, inspired by Nobel Laureate Giorgio Parisi’s pioneering flocking studies, embodies “the power of collective intelligence — an emergent awareness that transcends individual cognition.”

“Chus Martínez’s visionary approach champions arts’ capacity to drive social change. Her exhibitions create space for exercising new connections and modes of awareness and encouraging meaningful dialogue across disciplines.”

Martínez adds: “At a time when fantasies of domination – technological or otherwise – threaten to upend our sense of equality, we urgently need spaces that train free thought. A relevant society is one where many forms of knowledge flourish, inspiring new languages for thinking and feeling together.”

Participating artists include: Adrian Mauriks, Agnieszka Polska, Alan Craiger-Smith, Alexa Karolinski & Ingo Niermann, Alexandra Copeland, Angela Goh, Ann Lislegaard, Anouk Tschanz, Anthony Romagnano, Barbara A Swarbrick, Benjamin Armstrong, Brent Harris, Carol Murphy, Daphne Mohajer va Pesaran, David Noonan, Derek Tumala, Din Matamoro, Eduardo Navarro, Gracia Haby & Louise Jennison, Harold Munkara, Heather B Swann, Helen Ganalmirriwuy Garrawurra, Helen Maudsley, Ian Wayne Abdullah, Inge King AM, Ingela Ihrman, Jane Jin Kaisen, Joan Jonas, John Pule, Josie Papialuk, Judith Pungkarta Inkamala, Julie Mensch, Kate Daw, Lauren Burrow, Liss Fenwick, Lorraine Jenyns, Malcolm Howie, Margaret Rarru Garrawurra, Marian Tubbs, Mel O’Callaghan, Mia Boe, Miles Howard-Wilks, Nabilah Nordin, Naomi Hobson, Noemi Pfister, Noriko Nakamura, Percy Grainger, Pippin Louise Drysdale, Rivane Neuenschwander & Cao Guimarães, Rosslyn Piggot, Rrikin Burarrwaŋa, Salvador Dalí, Taloi Havini, Tamara Henderson, Teelah George, Tessa Laird, and Tony Warburton.

Martínez has collaborated with exhibition designer Nguyen Le and graphic designer Ana Dominguez studio.

A series of publications, titled Art Museums Papers, authored by Chus Martínez, Laura Tripaldi, and Neha Cheksi will accompany the exhibition, offering further insights into its themes.

The exhibition will feature a vibrant public program featuring talks, performances and an opening weekend celebration with local and international artists on Friday 21 and Saturday 22 February 2026. Also built around the exhibition will be the Potter’s annual Interdisciplinary Forum under the theme of Intelligence on Saturday 9 May 2026.

This will be the second exhibition presented at the Potter since its re-opening in May 2025 following the acclaimed exhibition 65,000 Years: A Short History of Australian Art.

Potter Museum of Art