COMMISSIONS, 2025–2026

The remaking of things for WAMA Foundation

The Australian Jazz Museum: Tiny but Wild

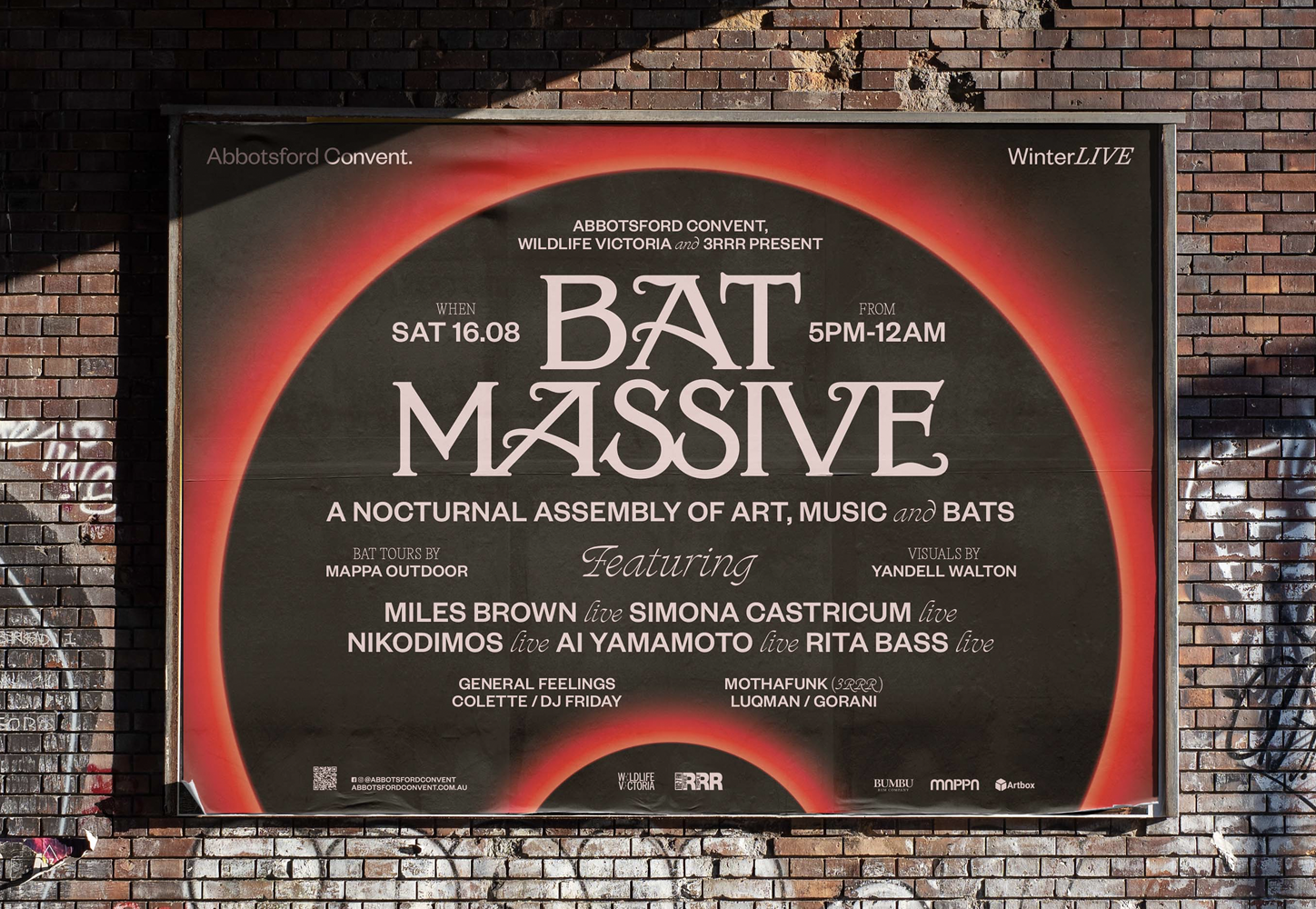

Bat Massive: A Nocturnal Assembly of Art, Music, and Bats, presented by Abbotsford Convent, Wildlife Victoria, and 3RRR

Gracia Haby & Louise Jennison

The remaking of things

2025–2026

Digital collage on vinyl

A reworking of our NGV commission for Melbourne Now especially for WAMA Foundation

National Centre for Environmental Art & Gariwerd/Grampians Gardens

4000 Ararat-Halls Gap Road, Halls Gap, Victoria

From Saturday 6th of December, 2025 – extended indefinitely (2026)

A second telling of The remaking of things (2023), a reworking of our NGV commission for Melbourne Now especially for the WAMA Foundation, 2025–2026.

The remaking of things is collaged from 100 pieces within the NGV collection, and depicts a pocket of restored eucalyptus forest habitat by the banks of the Birrarung for the Grey-headed flying fox (Pteropus poliocephalus), and all who fall beneath the care and knowledge of their wing. Coinciding with the WAMA Art Prize 2025, this second telling of The remaking of thing falls across two walls, and features scenes from the middle and the tail of the composition.

﹏

RELATED LINKS,

MELBOURNE NOW: THE REMAKING OF THINGS

THE REMAKING OF THINGS ARTISTS’ BOOK

RELATED POSTS,

TINY JANUARY

ON WALL, ON SCREEN, FORMED, AND FORMING

DRAWING SOON TO A CLOSE

AN OUTSTRETCHED WING

THE FOLDING OF PAGES

ARTISTS-IN-RESIDENCE

IN THE COMMUNITY HALL

WHAT IF YOU COULD GROW A FOREST FROM A COLLECTION

SMALL, ARBOREAL, NOCTURNAL, OMNIVOROUS

SILVERED

LISTENING

COMMISSIONS & WILDLIFE FOSTER CARE REALLY DO GO PAW IN PAW

FROM CLOVER TO PELÉ

THE SOFTEST OF RELEASES

GROWTH

THE BEGINNING

Gracia Haby & Louise Jennison

Tiny but Wild

Digital Collage and design

2025

For the Australian Jazz Museum

One very exciting way you can support us is through the Australian Jazz Museum and their recording, also called Tiny but Wild, like our wildlife shelter. We loved creating the artwork and design for this album especially for the Australian Jazz Museum, which in turn supports our home-based wildlife shelter.

The album launched on the 14th of February, 2025.

Please head to australianjazzmuseum.bandcamp.com to order Tiny but Wild (download available in 16-bit/44.1kHz)

●

Tiny but Wild is an eclectic album of Australian jazz, compiled by the Australian Jazz Museum, with the goal of showcasing contemporary, original, Australian jazz. All tracks except ‘The Bat’ (Pat Metheny) are original compositions.

Where did the bat idea come from? Dan & Ian just kicking around ideas for a project based around a cause, about 7 weeks back.

Custom artwork for this project was created and donated by Melbourne artists Gracia & Louise. The Australian Jazz Museum will donate profits from the project to support their wildlife rescue cause, Tiny but Wild.

A huge thank-you goes to the musicians on this collection, who have kindly donated their track for project-specific use on this album. Please check out their other works and support them.

The Australian Jazz Museum was established in 1996 (originally as the Victorian Jazz Archive) and has been preserving music, video, printed items and instruments since. We are run by volunteers without external funding.

Please visit our website ajm.org.au to find out about Australian jazz preservation, volunteering, membership and donations.

The Australian Jazz Museum

World Builders essay for Bat Massive: A Nocturnal Assembly of Art, Music, and Bats, presented by Abbotsford Convent, Wildlife Victoria, and 3RRR

Tee Mitchell

16th of August, 2025

Look up! There’s a camp of fruit bats on the banks of the Birrarung, at Yarra Bend. See how they dangle above, sheathing themselves in thin, black, membranous wings, with only their faces exposed to the late afternoon cold. Most are like this, silent and still, watching with inscrutably curious eyes.

A few others have risen early and started to preen, cheep and sneeze. An occasional cackle cuts across birds bolting between the mid-storey shrubs. Others languidly stretch out their wings, flashing rusty-red collars, grey fur, wiry feet.

The sun sinks lower and more noises come, huffing, trilling, shrieking, rustling and the soft thump of wings beating air. Nightfall brings a collective upswelling. Thousands of grey-headed flying foxes will disperse over Naarm, into backyards and bushland and suburban parks.

…

Here, de la Bellacasa reframes care as a fundamental ethical obligation that also extends to non-human others. She espouses the situated nature of care, and ways in which it is shaped by context, history, power and interdependencies that can’t be ignored. This idea of ‘thick care’ takes Donna Harraway’s observation that ‘nothing comes without its world’ as its starting point.

“This being so,” Bird Rose observes, “we are called to consider others not as passive bodies but rather as thinking subjects inhabiting their own worlds of action and meaning. A world, in this thick account, includes the body, the self, the relevant environment, and the interweaving matrix that holds these elements in the dynamism of ongoing life. In the interfaces between species, thick care must be attentive to many particulars. With flying-foxes there will always be much that we humans do not understand, but we are called to recognise that flying-foxes do inhabit their own worlds, and that our care must engage with enough elements of flying-fox life to ensure that both the body and the integrity of the individual’s world are sustained.”

These flying fox worlds are shaped and remade by modes of understanding, paying attention, learning, remembering, and adapting behaviours. They feature specific sensitivities inherent to the species at large, but also unique to individual bats, whom carers come to know intimately over weeks or months.

Louise Jennison and Gracia Haby run a wildlife shelter at their small home within five minutes drive of Yarra Bend. “Every bat has a personality,” says Louise, “and these traits start to show from the moment you meet them. When some come into care, they’re terrified and overwhelmed. Some take to care easily, with an extraordinary amount of trust.” She has known bats to be bold, bossy, meek, flighty, affectionate, humorous and always intelligent. These individual attributes contribute to a world characterised by the species’ collective, communicative, and empathetic nature, which is why bats are almost always cared for alongside others of their kind. Such forms of social organisation and bonding are most apparent in flying fox practices of caring for young.

Mothers gestate for six months, and give birth to a single pup, whom they carry in flight for its first three or four weeks of life. Once pups become too heavy and cumbersome to carry, they are left in a crèche throughout the day. At around three months of age, they start to fly and venture out in search of food, learning from each other under the guidance of older males. Pups are fully weaned and become independent at roughly six months, but maintain significant site fidelity to their maternal roost throughout life.

“Their relationship with their mum is such a tight bond,” Louise says, “so young pups come in grieving, under really traumatic circumstances. You also have to help them through that grief.” She and Gracia chatter to their charges and give them names. They recognise the meaning of several calls, including a pup’s unique cheep around dawn.

This is one of more than at least 30 discrete vocalisations with specific meanings; in this case, it helps mothers find their pups as they circle the camp after returning from a long night of foraging. Louise and Gracia come to recognise the specific sounds of each pup in their care.

The process of raising pups is very hands on. The youngest begin their time in care inside an incubator. They’re taught how to toilet correctly, fed five times a day, and love to be cleaned and groomed. “We use this tiny little eyebrow brush,” Louise says. Eventually the pups graduate to a larger enclosure festooned with fabric so they can explore and learn to climb, stretch their wings, and prepare for the transition to an outside aviary where they take their first tentative flight.

These relationships are unique and specific; bats also differentiate between human beings. “From what I've observed, not every bat in care is just going to accept any human,” Dr McCutchan says. “So you could have a new volunteer come into the shelter and the bats aren't impressed, and they will actively move to the other end of the aviary, away from that person who's doing the cleaning. Whereas if it's someone that they're familiar with, they barely bat an eyelid.” Sometimes carers get to know dozens of bats in one season.

There are periods when the need for rescue and care is acute. In 2023–24, Gracia and Louise took in 54 pups. Dr McCutchan explains the factors that drove thousands of bats into care. “A lot of mums were seen to be starving, or the pups were just really weak,” she says. “We suspected the mums weren't able to produce enough milk, if they were still alive. Others were orphaned by mum being deceased. So, a lot of the pups were coming in dehydrated and very skinny.”

While humans almost certainly fuelled this wave of emaciation through habitat clearing and other pressures, some people also responded with care. An organisation called Friends of Bats and Bushcare is planting trees at Yarra Bend, and the state has also moved to provide some relief. A new sprinkler system has been installed near the camp to mitigate the impacts of extreme heat, and detailed management plans now exist to guide response and rescue efforts during mass death events. Clearly, this marks a departure from the uncaring approach Ratcliff described.

The new millennia has ushered in novel and more diffuse forms of violence, like climate change, yet it has also engendered some restitution of care, and there are many people who seek to respond to a deeply felt ethical call to become attentive to animal worlds and ways of being. Nagle contended bats were among the most alien creatures, and certainly, there is much we don’t and may never know, but there are striking similarities too. As Nagle observed, it’s unlikely we will ever know what it’s like to be a bat, but some people do have the pleasure of getting to know one, and while not everyone can become a flying fox carer, we can all become more attentive to their creaturely worlds.

Read online (Bat Massive event listing)

Listen online (Abbotsford Convent soundcloud)

BAT MASSIVE

Tee Mitchell is a journalist, writer and editor. They work on the lands of the Wurundjeri Woiwurrung and Boonwurrung people of the Kulin Nation, whose sovereignty was never ceded.

With thanks to: Dr Rodney van der Ree; Dr Jessica McCutchan, Senior Veterinarian, Wildlife Victoria Travelling Vet Service; Andrew Tanner, Senior Researcher, Wurundjeri Woi-wurrung Cultural Heritage Aboriginal Corporation; Gracia Haby, Tiny but Wild Wildlife Shelter ;Louise Jennison, Tiny but Wild Wildlife Shelter; Davita Coronel, Friends of Bats and Bushcare; Ava Graham, Mappa Outdoor Michael McAtomney, Mappa Outdoor